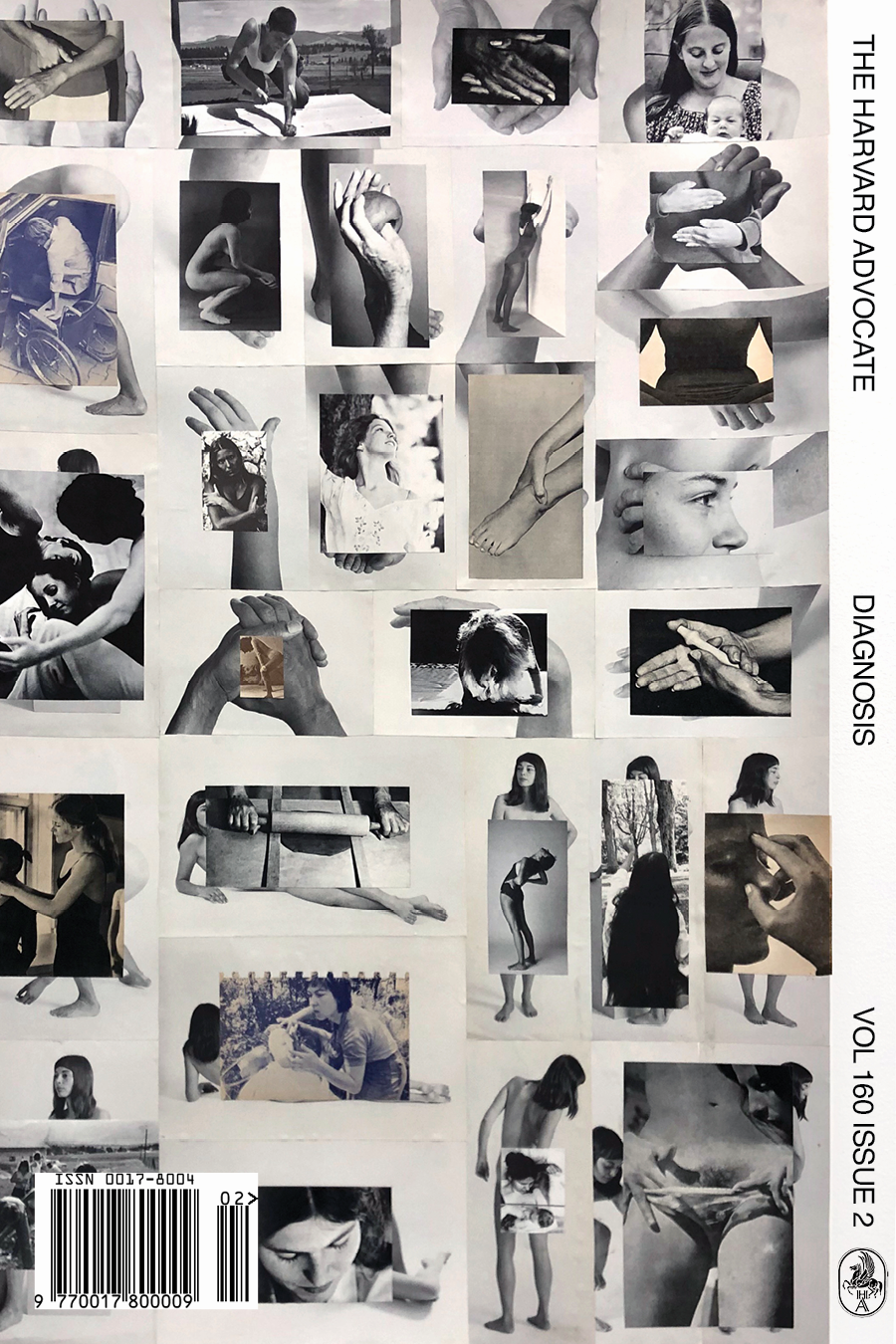

Features • Fall 2025 - Diagnosis

I was raised, for three years, in Virginia, where the elementary schools taught us that the Chesapeake was our bay, the Appalachias were our mountains. This was the Virginia I recall, singing an old folk song about the Shenandoah River Valley, Oh Shenandoah, the one that starts, “I long to see you,” and ends, “I’m bound to leave you.”

Poetry • Fall 2025 - Diagnosis

after Ellen Bass

O black bean boy, O owl eyes,

O package of muscle and fur.

My cautious companion, my

in-love-with-me friend. What will we do

without your low grumbles

your hot-water-bottle body

beside us all winter? O sun-scorched nose,

O wacky teeth that can’t bite a thing, O

fluted, veined callalily ears

taking the world straight to the heart.

There is no guy I’d rather sleep with,

no slinky tuxedo like yours.

When you frolic and hop

in your nightly routine, the sounds

of cracked glass and low howls

are like the heartbeats in a womb.

In that embryonic waterfall, we sleep.

Two lucky mothers.

O bloated bladder, O swollen,

sleepy heart. When we nearly lost you,

we sought you in our grief

to ease our grief. We held your exhausted body

to us. O seeing soul, O aperture closing and

widening, catching the landscape

of more than mere humans can know.

Beloved beast, dear body that heals and heals.

Tiny horse, honeyed contralto,

our leaping, whiskered seal —

Fiction • Fall 2025 - Diagnosis

W E The People entered the home of the Crisis Actor illegally. This is true. Why deny it? We certainly weren’t going to be invited in. There was the matter of him knowing our faces, from those days when we picketed on the gum-spotted sidewalk or confronted him at his car in a parking garage downtown, our accusations drowned out by the scrape of skater boys. And, of course, there was the restraining order. Legal lines had been drawn and, yes, we decided to cross those lines, which resisted no more ably than strands of cobwebs stretched across a basement doorway.

The fresh online pieces we experiment with outside of our print cycle. Formerly known as Blog.

Notes

The purposes of this review are twofold: first, to convey the eminently pleasant though not necessarily intellectually stimulating experience of seeing The Light in the Piazza at the Huntington Theater; and second, to convince you, yes YOU, the member of the Advocate reading this (or honestly whoever else) to take up my mantle of reviewing shows at the Huntington now that I have graduated.

From the Archives

Poetry • Fall 2011

She dreams of morning. Because the rusty lightcoats itself with inquisitive steam rising acrossthe body of water, small stone-fruits createfleshy knocks against the slick pane inside your mind,almost visible. Who is there to ask. Who would mind to inhabit that time, or to be that age once again. This morning, I watched a closely-trimmed dog,reluctantly panting, swallow the mist:he offered his own contribution of moistureto air. He chose not to feed, and instead gougedtufts of Bermuda grass pushing the wet earth aside and reserving space for the owl’s shadow.

Fiction • Winter 2019 - Double

This morning you sailed a boat.

Not only that, but you taught your best friend how to sail a boat, both of your bare feet slipping on the floor of the Sunfish, leaning out over the Maine lakewater against the tug of the wind on the mainsheet, laughing as she wiggled the tiller back and forth, forgetting if left meant left or left meant right, throwing caution to the breeze until you scraped up against some underwater rocks and you—you, thirteen years old, heart beating faster as you discovered this opportunity for responsibility, imagining the shawl of your mother’s care finally slipping from your shoulders—climbed out of the boat and risked the soft pink soles of your feet against barnacles that could cut like knives, just to push the boat back into open water and save the morning.

Features • Fall 2013

CLINIC 1K: ADULT NEURO-ONCOLOGY. The sans serif sign announces the location as if for a lemonade stand, or for a neighbor’s garage sale. But this is a place where brain tumors come in spheres the size of oranges, causing some to lose speech, some memory, some personality. A grandmother stutters when asked to state the day of the week. A defense lawyer can’t remember a simple list two minutes after hearing it. A man watches from across the room as his wife spins her wedding band around her finger.

These are the patients of Dr. Vandermonde, a cancer physician in Durham, North Carolina. A self-described “reckless optimist,” he sees roughly forty patients with brain tumors each day. His clinical presence is marked by a loud whisper and cans of Mountain Dew, and he insists his patients call him “Jim,” or at least “Dr. V.”

Most of Dr. V’s patients go through the same routine of procedures: surgery, radiation, chemotherapy. The average successful surgery removes close to 99.9 percent of tumor cells, leaving around 108 residual ones. Radiation—carefully aimed high-energy waves—burns through 99 percent of those that remain, leaving 106 to be treated by chemotherapy, often prescribed in the form of DNA-attacking oral drugs. When the tumor appears to stop growing, all treatments are dropped in exchange for quality of life, even though 90 percent are known to grow back in a more lethal recurrence.

From the perspective of the tumor cell, I would imagine that this treatment routine is quite different. After a life of darkness (save a skull-breaking freak accident years ago), a silver saw appears cut-ting through the dull bone of the skull. A hint of fresh air. The sheath of the brain is pulled aside like a wet curtain; the cells gasp for light while staring at a person in scrubs scooping away their relatives. Hours later, it is dark again. The cells dress in black, prepare their eulogies. But an invisible laser attacks the mourning cells and does away with the remaining majority. And finally, enraged, the last cells standing fight a losing battle with daily or twice-daily waves of identity-stealing macromolecules, engaged until there are too few left to matter to an oncologist.

It is no wonder they grow back stronger.

Some attribute the field of surgical oncology to Guy de Chauliac, a 14th-century physician of the French clergy. He cared for three Popes in both life and death: while they were alive, he acted as their physicians, and once they were dead, he aided in preserving their bodies. Only after their death did he take to using a scalpel, curious to map human anatomy. He was the first to suggest that “Cancer must be cut out early with a knife.”

That was a time when cancer was thought to be caused by black bile, when limb amputation was not unusual treatment, and when anesthesia was nonexistent. By contrast, in today’s “operating theater,” there is a drill, a team of nurses, and an anesthesiologist. There is also a vertical sheet. On one side is a brain, and on the other is its owner, Margaret, awake. A grandmother of four, she listens carefully. As Dr. Phillips, the surgeon, considers cutting a certain area of the brain, he first stimulates it with an electric current. “Go ahead and move your left hand, Margaret,” he says. She gives it a slow wiggle, and he goes on to stimulate a different region. “Now yesterday was Wednesday,” he says. “Can you tell me what day it is today?” She stutters, and so he stops.

Intraoperative brain mapping, as it is called, allows the surgeon to deal with a brain that we don’t fully understand. He drills through the skull, locates the tumor, and removes the malignant cells with care, crossing creases and folds, navigating a geography of memory, perception, speech, and emotions. This is how he tries to win the battles, and eventually the war.

“Dog, tree, bicycle. Can you remember those for me?”

Dr. V pauses as he gives a routine diagnostic exam to his patient, Martha, a middle-aged lawyer and mother of two who suffered brain damage from x-rays during radiotherapy.

Physicist Wilhelm Röntgen discovered the x-ray over a century ago, unearthing its unique role as a carcinogen, cure, and diagnostic tool. Only months after his November 1895 study, members of the medical community began experimenting with the ray’s unknown properties. (There is little coincidence in its namesake, the unknown mathematical symbol X.) Radiologists used the skin of their arms to test the strength of radiation, looking to measure the minimum effective dose, many of them later diagnosed with leukemia. A medical student in Chicago began using x-rays to treat diseases. Röntgen himself scanned his wife’s hand, showing her a picture of her own skeleton.

Her response—“I have seen my death!”—foreshadowed the ensuing difficulties with x-ray treatment. Early radiotherapy sessions consisted of a single large dosage, often curing the disease but also later killing the patients. In today’s radiotherapy clinic, treatment has reached a much higher level of sophistication: Particles are accelerated, shaped to fit the tumor’s size and contours, and shot through a focused laser beam. But there remains a trade-off between killing every last tumor cell and damaging nearby healthy tissue. Tactical warfare ensues.

Dr. V proceeds through the remainder of the exam, asking Martha to lift her arms and legs, to listen for a faint noise, to follow a movement with her pupils. Lastly, he returns to the test of memory. “Do you remember the three objects I told you?”

Martha squints, fighting off the damage, tapping into her reserves of memory. “Can I tell you about my children?”

The early roots of chemotherapy are traced to a WWII battle, when German bombers raided. Allied forces in 1943. A U.S. military ship, John Harvey, contained a secret cargo of 2,000 mustard gas bombs, reserved for retaliatory use in case the Germans resorted to chemical warfare. When German bombs unexpectedly hit the ships, U.S. troops were unaware of the gases released, and 628 were poisoned and rushed to hospitals. There, physicians noted a depletion of the soldiers’ lymph nodes, organs of the immune system known to be especially inflamed in some patients with cancer.

From this incident came Mustine, the earliest form of chemotherapy, which successfully reduced tumor size through destruction of cancer cell DNA. But it also targeted other rapidly dividing cells in the body—those in bone marrow, the digestive tract, and hair follicles—causing predictable side effects in patients. The model for modern chemotherapy remains largely unaltered: Malignant cells comprise the majority of the fallen, but the drug cannot fully distinguish friend from enemy.

In the clinic, toleration of chemotherapy is often mixed. As Dr. V enters the room to meet his patient, he offers a warm “How’re we doin’ today?” in his usual raspy chord. Robert, 32, sits in the patient chair, although he may as well be lounging on his couch watching football. His face is a deep red, and his globular stomach renders the leprechaun printed on his shirt three-dimensional. “Nowhere else I’d rather be,” he says with a smirk. His wife, beside him, rolls her eyes and squeezes his hand.

Robert starts to talk about his biopsy, which he had just days ago. “So there I was, sitting in the chair as they were trying to lock this thing onto my skull.” This is the metal device used to keep the patient’s head still and mark the drilling area. “They kept fidgeting and fidgeting and finally they got it. And man, was that thing gripping the hell out of my skull. I was going to call up Disney and tell ‘em they need to make a ride out of this thing!’’

His wife laughs, as does Dr. V. The three ex-change stories, Robert is prescribed chemotherapy, and they leave.

Three months and a round of chemotherapy later, they return to the clinic for a follow-up. As Dr. V comes in, Robert sits with his arms crossed. His stomach has shrunk, and the whites of his eyes are dull. His wife stares at her own lap, fidgeting with her ring finger.

Dr. V delivers good news: The tumor has receded, his condition is stable, and he won’t need to return to the clinic for another six months. Robert’s wife stands up and gives Dr. V a hug.

“Not bad news, huh?” says Dr. V as he grip’s Robert’s shoulder.

“Yeah,” says Robert, pursing his lips.

As intended, Robert’s tumor had been robbed of its DNA, or identity. Only Robert had been robbed of his, too.

Tumor cells, they glisten a fatty white, skip from tumor to tumor, invade fresh ground like steadfast soldiers. It’s their corps against ours, mutant versus wildtype, a carnal red clashing with a bathroom-tile beige. Cancer, a metaphor for battle: Is it a coincidence that the operating room is called the theater, that radiation doubles as a weapon in warfare, that chemotherapy was discovered in a world war?

There are the simpler similarities between war and cancer: that war is a battle for freedom, that health is a form of freedom, that both are fought by humans. But there is a deeper sense of likeness as well. Any two cells in battle—one healthy, one malignant—share over 99.9 percent of their genes. Any two humans in battle—one from the Allied, one from the Axis—share 99.9 percent of theirs. Both cancer and war entail a form of self-harm, leaving us to grapple with the paradox of hurting to heal. They require us to draw from human tools of inquiry to fully internalize the narrative of loss. Literature professor Haun Saussy, who writes on the politics on loss, holds a view of disease that applies equally well to both: “An adequate explanation of what has gone wrong [...], as opposed to the remedies to be applied to its effects, may demand the talents of the geographer, the economist, the historian, the hydroelectric engineer, the novelist.”

There is also the etymologist. When Hippocrates, namesake of the modern physician’s oath, found swollen veins surrounding a tumor to resemble a crab’s limbs, he named the disease after Cancer, a giant crab in Greek mythology. As the story goes, when an affair involving Zeus produced Heracles, Zeus’s wife Hera vowed to have the illicit son killed. In a violent battle between Heracles and a many-headed serpent, Hera sent the giant crab to aid the snake in slaughtering her husband’s son. Cancer nipped at Heracles before being smashed by his foot.

As a reward for its service, Hera placed the crab’s image in the night sky, only for it to watch another human family fight its own kind.

Poetry • Winter 2016 - Danger

I am that comet you all have cursed,

in the dark void drifting aimless and unsettled.

Love me like an avenger's lost

last chance at revenge.

I am that person whose shadow was carved on the tree,

and from that day on taken for dead.

Love me like a hallucination

in a crazed killer's fevered brain.

I am that wheat that Heaven too has singed with fire,

that has shivered even from the dog days' sunlight.

Love me like a masochist.

As you cherish reason when the unreasonable surround you.

I am that wolf whose cold bright bones the witch doctor holds in her hand.

To soil, to air, to flame, to water I will scatter like a spell.

Love me like miracles not seen even when sun and moon align

in the sixth degree under the sign of the ram.

August 25, 2004, Ürümchi

*Translated from the Uyghur by Joshua L. Freeman. See another of his translations *

*in the Advocate [here](../../../../article/563/old-era-or-wolf-girl/). *

* *

Poetry • Winter 2013 - Origin

It is the nature of this game to want possession

then to want to give it up

to get it back so you can give it up again.

Nobody stops to ponder the ball, the way John Keats

pondered a cue ball’s “roundness,

smoothness, volubility”: its joy in being hit.

Imagine the score is tied, and I take the ball away

In order to sketch it, or incorporate it

Into some kind of quasi-tribal dance routine...

I thought we had agreed to play. I thought you said

We’d play and play all day, beating and being beaten,

Taking turns at losing, learning its advantages

for a young man’s character, then changing fates.

What kind of game is this, your going away forever,

sending word, years later, that you’d died?

Poetry • Winter 2014 - Trial

Call me drag

anchor *ab extra*

on the download

Tiresias 2.0

[x and—not then—y]

abridged. Call

update infected

attachment white

cell count plate-

let and own

house-mowed home

wanna-be hull.

Call me fresh

new coat of age

swamping blind pig

failed footage

cracked monocle.

Call me K

always on my way

to some benighted castle

uppermost prison

right of left

unstamped stockade

illegible keys.