Fredric Jameson passed away at the age of 90 on September 22, 2024. Renowned as the Knut Schmidt Nielsen Distinguished Professor of Comparative Literature at Duke, Jameson was a profoundly influential figure in Marxist literary criticism. Jameson studied continental philosophy under Erich Auerbach and Paul de Man when the winds of Anglophone academia were still blowing west, and produced a body of culture criticism in the Western Marxist tradition that would culminate in The Political Unconscious, published in 1981. His next major work Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism has become even more salient to our present day understanding of the commodification of time, space, and culture. Jameson was an ambitious and prolific critic: his analysis spanned the gamut from architecture to film to novels, and even in his final year he published three books, Mimesis, Expression, Construction; Inventions of a Present; and The Years of Theory.

When I reached out to Homi K. Bhabha, the Anne F. Rothenberg Professor of the Humanities at Harvard University, regarding a tribute to Jameson on September 23rd, he responded within five minutes; it was the first that Bhabha had heard about his colleague’s passing. It used to be a departmental tradition to distribute black envelopes on these sad days, but those had gone the way of budget cuts. Bhabha is a founding figure of postcolonial studies and a leading thinker in migration studies, cosmopolitanism, and human rights. Like Jameson, Bhabha is interested in the question of cultural production. His 1994 essay collection, The Location of Culture, took the academic world by storm for his conceptions of cultural hybridity, mimicry, ambivalence, and Third Space. He argued that cultural production and identity formation occur in the discursive space between colonizer and subject; “culture” is but an ongoing negotiation.

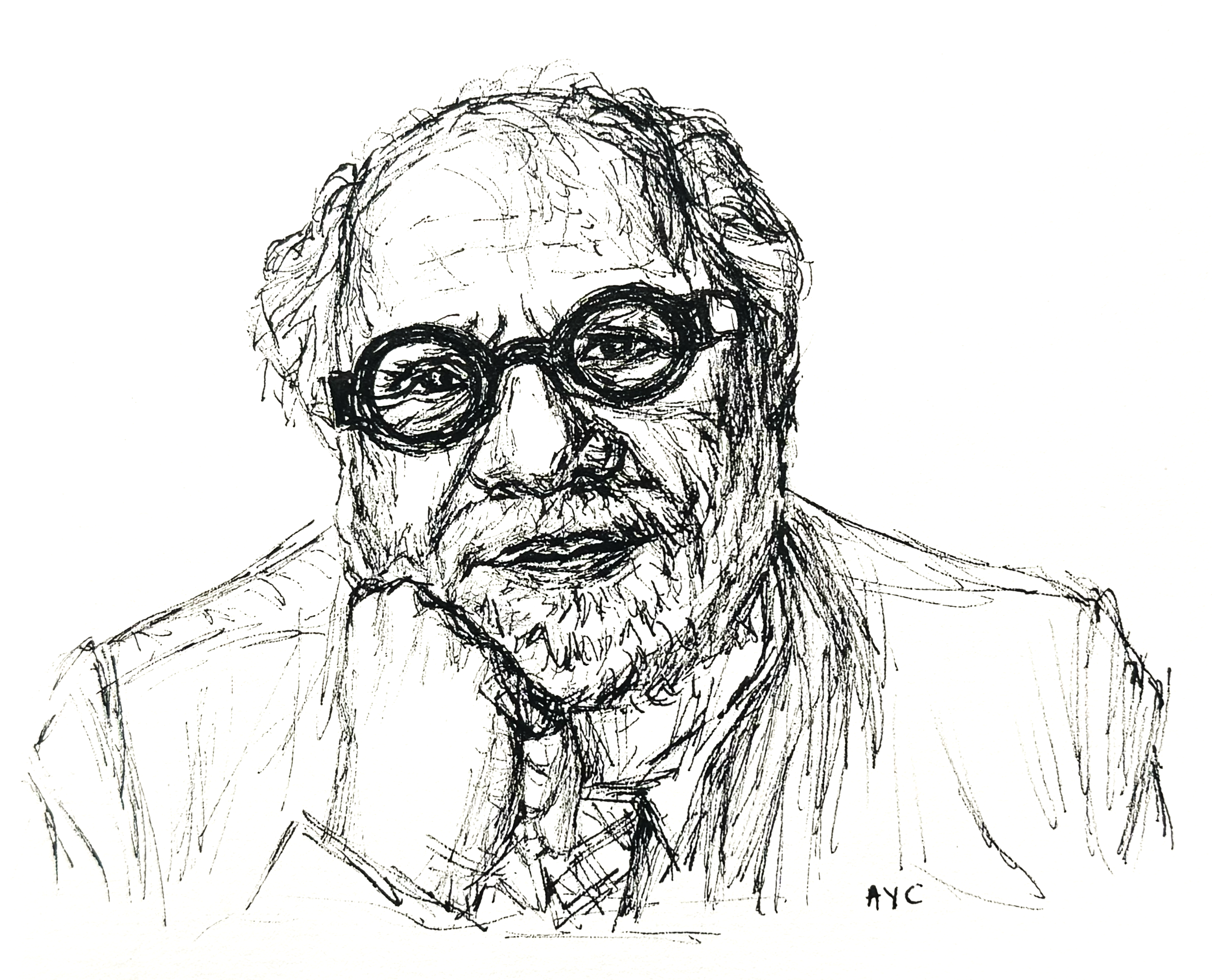

Two months later I am meeting with Bhabha in his home office on Zoom; he is wearing a lime-green sweater; he has just returned from London. Instead of the Le Corbusier-style black, round glasses I had seen in too many photos online, he is wearing a lighter tortoise shell pair. Tirdad Zolghadr had asked in Bidoun magazine’s 2006 interview with Bhabha, how do you conduct a good interview with a walking institution? In preparing to talk with Bhabha about Jameson I faced a bigger dilemma — how do you conduct a good interview with two walking institutions? Read voraciously ahead of time, for one, but above all, listen: to Bhabha’s resounding Indian-British timbre, resolutely intelligent.

FRANK Y.C. LIU: Professor Bhabha, you have described Professor Fredric Jameson as “a major influence, above and beyond.” Before we get to Jameson the critic, let’s discuss Jameson the man. How did you come to know him?

HOMI K. BHABHA: What I do remember, funnily enough, is that as a graduate student at Oxford, my tutor, Terry Eagleton, who was a good friend of Fred’s, called me and said that Fred Jameson needed some research done in the Bodleian Library — would I be willing to do it? I said, “Absolutely,” and I remember that I did the research he wanted on a relatively unknown work by Samuel Butler, I believe, and gave it to Terry. Whether Terry told Fred that I had done it, I don’t know, and I very much doubt, but Fred was a generous and a large-hearted man. I know he was deeply interested in good wines and was very generous with his Duke colleagues and students, and they had many wonderful evenings in his home in the environs of the university. Fred was much loved and deeply respected by his students. I regret that I wasn’t so close to him personally, but we just didn’t have the opportunity.

FL: Was that the first time you heard about Jameson?

HB: I’d read him in the New Left Review, and carefully studied Marxism and Form and The Political Unconscious. I was stunned in admiration! What interested me particularly was that amongst the English-speaking critics who were interested in continental philosophy, structuralism, and post-structuralist Marxism, he was a specialist in French literature. So he had that indispensable background in the methods and materials of comparative literature; he was schooled in French literature and history; and he was well aware of French colonization and its influence on metropolitan ideological preferences and social prejudices. Jameson brought something very different to the game. Many of the other critics I read were resolutely anglophone, although they were skilled theorists. Fred brought a larger cultural palette to the landscape of national and regional cultural production. He was a francophone Europeanist whose attention moved to the “Third World,” and was something of a Sinophile too. He had a very capacious and adventurous intellect.

FL: What does studying francophone postcolonial nations and their literature add to the conversation?

HB: I think these differences go back to the way in which the French constructed their sense of colonial “cultural” subjectivity. In the French tradition, if you were happy to shed yourself of your own cultural lineages and genealogies and swear allegiance to the French Republic, then you were welcomed as French — but up to a formal, political point. Bereft of your own history, standing naked before the French flag, you were, inevitably, an object of colonial racism. Your identity as a Black or Maghrebian French colonial citizen might be accepted, but your ontology as a free and equal human being was rarely recognised without being racialized. This is where the Martinican political activist and philosopher Frantz Fanon joins the debate and casts his long shadow over our current discussions of decolonization, postcolonialism, Black Lives Matter, etc.

FL: We remember The Political Unconscious for bringing the francophone Western Marxist tradition into the English speaking sphere, specifically America. But perhaps the work that left an even bigger impression in popular memory was Postmodernism, or The Culture of Late Capitalism. You reference it in various essays throughout your collection The Location of Culture. Do you find his concepts helpful?

HB: I think you’re right. One of the significant qualities of his work was the way in which he used theory and history to engage cultural form — literary, cinematic, architectural, urban, dramatic — as much as he was concerned with mimetic content. This emphasis on the formal constructions and conventions of cultural genres gave his work aesthetic nuance in the exercise of political power. There was nothing reductionist about his writings, nor did he create cookie-cutter “politically correct” readings. He was a great Marxist structuralist critic in the tradition of Lucien Goldmann who had absorbed psychoanalytic ideas and various other discursive traditions. He had an encyclopedic imagination.

FL: His texts included the art world, architecture — his work has been really influential there — science fiction, political economy, consumer culture, et cetera... He spans a very, very wide gamut.

HB: He does. I was just thinking as you were speaking, that he’s very interested in cinema and theater too. He spent time in China and engaged with post-Maoist aesthetics and ethics. Jameson was the patron of a generation of very talented Chinese students who worked with him at Duke and are now distributed at universities across the American academy and beyond.

FL: I was just on Chinese social media a couple days ago; they really do adore him. One reason is that he came in during a transitional period in the Chinese government’s conception of what Marxism exactly is, and disillusioned academics latched onto that figure of Jameson as a staunch Marxist critic, a patron as you say. His ideas of postmodernism really rang true in nineties China.

HB: You are so right about this. Jameson’s openness to periods of historical transition, as in China, was reflected in his method of inter-mediatic cultural analysis. His writing spanned the spaces between literature … politics … cinema … aesthetics … urban and rural development. Yes, he constructed his relational theory to bridge the ellipses in my previous sentence — and more. Each connection signifies another adventure in thinking across diverse mediums and bridging different cultural codes. For instance literature and cinema are linked by literary motifs that influence cinematic language, and vice versa. Theater and opera are almost kissing cousins. Dramaturgy and choreography have many performative aspirations in common. Jameson had a nuanced insight into these intersections and interrelationships.

FL: One of Jameson’s more controversial claims is from “Third-World Literature in the Era of Multinational Capitalism”: the idea that “the story of the private individual destiny is always an allegory of the embattled situation of the public third-world culture and society.” Do you think that’s true of nationality in literature?

HB: I think that’s certainly true, although, in my view, this is a somewhat mechanistic description of an important problem. The embattled allegorical relationship between private destiny and the “public” sphere is no less embattled now in “First World” societies than it is in postcolonial countries. That embattled situation is differently structured, of course: developing countries have large agricultural populations that have to compete with industrial development at a cost to themselves; postcolonial countries are often in corrosive debt to Western banks and governments. In addition, there are constraints on resources, literacy amongst the poor lags behind the rising middle-classes, and public education is unevenly distributed. This creates a situation in which “the poor” (however you define it) are manipulated by corrupt, authoritarian leaders who buy themselves into power, and create spirals of corruption all the way to the top. Western ethno-nationalist populist and racist regimes, supported by billionaires and oligarchs, create their own “Third Worlds” within their “First World” sovereignties. Migrants, minorities, dissidents, the discriminated, the homeless and the poor, are embattled by public spheres that exercise their hegemony by “racializing” those who belong to different faiths and cultures, even though they make a crucial contribution to society whether they are citizens, residents, refugees or “undocumented.” The latest instrument of oppression is ultra-nationalist patriotism that results in Brexit in Britain and MAGA politics in the US.

FL: It’s hard to not think about the recent reelection of President Trump when you talk about nationalism. He represents a tightening of national borders and tougher views of immigration in the US, but obviously that becomes an example to the world.

HB: You’re right. I don’t have anything to add to that. I think that all these policy initiatives have already been announced, and now we have to wait to see how much he’s able to push the boundaries of a democratic state, or how much longer democratic institutions and the rule of law will prevail. But we can’t say anything about this until we actually see what happens. I’m not looking forward to it.

FL: Do you think we’re living in postmodernity, or will we leave it for a new era at some point?

HB: I’m not so sure what you mean by postmodern living. In India, there are rural communities without electricity who cook with open fires fed by wood that extenuates the environmental crisis caused by deforestation. India also has some of the leading software and programming industrial campuses. Is that a postmodern way of life? If, in America, you deny women the right to choose the destiny of their bodies, while producing driverless cars and private space-shuttles, is that postmodern?

FL: Well I think for Jameson, a lot of what characterized postmodernity was its cultural implications; the breakdown of historicity and spatio-temporal awareness; alongside a lack of ability to regard what’s happening to other people around us at the same time, or in other parts of the world.

HB: We have a genre called the postmodern novel or postmodern film. But what would a postmodern economy be? Or, what would a postmodern legal apparatus say? We can’t say we are living in a postmodern age until we can think of institutions and structures that shape society as being “postmodern.” Is election denial postmodern? Is vaccine denial postmodern? I think we need to have a different type of conversation, a different starting point if we really want to make inroads into these more complex ideas.

FL: Perhaps we can think of postmodern consumer culture as when you “don’t have to think about Third World women every time you pull yourself up to your word processor.”

HB: There is a deep penetration of iPhone culture in rural India, in rural Jamaica, in rural Africa, in the Amazon. The iPhone has become a mode of communication, and in parts of Africa, a facility for banking and accounting. Just because the facility of the iPhone is global, its value as a personal possession, or a social symbol, or a cultural and economic “instrument” is defined differently in the context in which it is used.

FL: That’s very true. I was just in Sierra Leone this summer doing health research. And yeah, most people had a smartphone; it was necessary to access basic governmental functions, and they were also accessing the exact same social media that we were. I’m not sure if there’s awareness from our side though.

HB: It’s ubiquitous. I think one would have to modify the idea that when you sit down at your computer, you don’t think of the “Third World,” of women, men, children, or dissidents who are being crushed internationally. I’ve been thinking of all these things for decades when I switch on my computer.

FL: I don’t know if most people are thinking as much as you are! My dad was half-joking — this was pretty dark humor — about how lucky it was for him to grow up in China, which somewhat infamous for censoring the outside internet; he felt bad for the people I was working with in Sierra Leone who had full, unfiltered access to what was happening in America society at every moment. In China they wouldn’t have known how well off the US was at the time; perhaps this knowledge contributes to a sense of unwellness.

HB: You’re absolutely right! I think we have become aware of the global presence in the 21st century. We are in 2024 now; since 9/11 the world has been at war in some place or another, and very often at several places at once. We are aware of repression and oppression. We are aware of military campaigns, which may have rightfully ridden dictators, but have left those societies completely at a loss now. Furthermore, since 9/11 there has been raging migration. People have had to leave where they live because their life is unsustainable in so many countries, in the Near East and in Asia and so we cannot forget what is happening over there. There are 200 million displaced people in the world today, more than the population of Great Britain.

FL: Do you think migration has gotten enough recognition? What interests and confuses me is that we see information about migration on the news every day, and politically it’s an issue people obviously have had on their minds. But it seems like we haven’t made that much positive progress or inroads when it comes to solving it?

HB: Not enough adequate progress is being made. Migration and immigration are prime issues in every political election these days. As you know in the recent US elections it was a major issue, and we see the same with Brexit and the growing authoritarian politics in Europe.

FL: Where do you think migration studies or policy should go in the future?

HB: I’m not a policy person, I can’t really make policy for you. But I think people have to understand why, particularly with climate change and political unsettlement, people need to move. People need to move in order to make lives for themselves, to make life possible. They are not leaving because suddenly they think there’s better housing in Sweden than there is in Sudan. They’re leaving because they cannot make a living. They’re leaving because their children don’t have health provisions, proper housing, or education. They’re leaving their own countries, sometimes in fear, sometimes starving, sometimes in response to international wars or civil unrest stirred up by their own leaders. Countries of the global North and the global South are complicit in this degradation of international polity and the destitution of everyday living with some measure of civility and dignity. They deserve, as human beings, to cherish the hope of a second life. I was talking to a German colleague this morning who told me that one of the new German political parties which is very anti-immigrant, very anti-refugee, is based in a part of the country where there are no immigrants, no refugees.

FL: When you talk about the figure of the migrant, I’m immediately reminded of the theme of this issue of The Harvard Advocate, “LAND.” When we first introduced the idea of the Land Issue, people brought different interpretations to the table: environmental degradation, land occupation and displacement, and the crossing, breaking, and enforcing of boundaries. It seems like the migrant can be a figure that unifies all of these different questions of land. For example, environmental degradation is a cause for migrants to cross boundaries —

HB: You mean climate change refugees?

FL: — Yes! That was the term I was looking for. Should we think of land as a global resource for everyone, or, on the other hand, split it up into everyone having a small plot?

HB: My dear Frank, I can’t — you know, we can’t. This would not be an important conversation. Nobody can legislate that everybody in the world should have 10 acres and a donkey! You saw something like this promised to African Americans during Reconstruction and then snatched away from them ruthlessly with mendacity. We need to change our whole view of the Earth’s surface as a shared time-space — without territories of sovereignty — and then think about the historical, cultural, and moral claims attached to being linked to each other by way of “land.” We could learn serious lessons from indigenous, aboriginal, and tribal peoples about sharing the land with non-human species. The law has made some progress in recognizing mountains and rivers as legal subjects.

FL: Best restaurant in Harvard Square? You can say they’re all bad.

HB: No, I like some of them. My very favorite restaurant is Giulia. I like the Hourly. And I like the ramen house on Mass Ave —

FL: Santouka?

HB: — Santouka! And then on Cambridge Street, I like the Portuguese restaurant, Casa Portugal. Very, very simple restaurant full of people from all over the world: Portuguese, Portuguese speakers and eaters from Latin America, African-Americans, and many students and colleagues from across Cambridge universities.

FL: I heard that you like collecting fountain pens?

HB: I do like collecting fountain pens … You know, a great collector of fountain pens was Professor Edward Said; he had wonderful fountain pens. I like a good fountain pen, but I’m not a great collector of fountain pens.

FL: What pen do you use the most?

HB: I use the Montblanc —

FL: That’s the 149. Or it could be the 146. This used to be a hobby of mine.

HB: — I don’t know what model but it’s wonderful. And I also like this Japanese pen called Sailor, or something like that … It’s very good. Is there a pen called Sailor?

FL: Yes, there is. It’s one of the three big Japanese brands.

HB: Here is my Sailor, it’s wonderful. And I usually buy them in India, because in India, particularly in the area where all the lawyers have their offices, there are these wonderful pen dealers, because apparently Indian lawyers buy huge amounts of fancy fountain pens. So I buy most of my fountain pens in India.

FL: Same with me in China! In China and Japan, fountain pens are still ubiquitous. Last gift you gave or received?

HB: Last gift I gave and received! The last gift I gave is a rather splendid handbag I bought in Cambridge, England when I was there lecturing three days ago, and I bought it for my daughter. It’s a witty hand-crafted lady’s bag that looks like a kid’s school satchel … It’s very smart. And the last gift I bought myself was a new writing desk for my home.

FL: Is that the one you’re on right now?

HB: No, the desk right now is one I brought from England, an old pine “director’s desk.” But the one I’m getting is a walnut desk made in the 1930s, in Italy. It’s a wonderful object.

FL: Who’s the first person that reads your writing?

HB: I usually read some of it to my wife, you know, she’s a lawyer who specializes in immigration and human rights law. Oh yes, there are three people: One is Jim Chandler, a very close friend at the University of Chicago, and another is James Simpson, one of our own colleagues who has since retired. A third person who always reads my work, and maybe the first person who I send it to, is my research assistant Paul Chouchana. He is a graduate student in the Department of Comparative Literature. When she has the time, I request my assistant Matilde Morales, also a graduate student in CompLit, to take a look.

FL: And finally, what do you think is the most valuable advice you would give college students?

HB: I have two interconnected bits of advice, so they really are part of the same thing. Always try — always try! — and work on something that you are interested in, and find challenging at first. Easy answers are deceptive. Being challenged, being doubtful, tearing your hair out and nervously stroking your beard — all these are essential to thinking hard and well! So always go for what interests you the most, however complicated or problematic it appears to be. And once you’re caught in the storm of ideas, hold the rudder tight and never give up. There’s plenty of time to rest once you reach the shore, “on the other side,” that you once saw only as a blur on the horizon, and is now, suddenly, the ground beneath your feet.

FL: Thank you, Professor Bhabha.

HB: What a pleasure talking to you, Frank.