"The Matriarch" is the 2025 winner of the Louis Begley Prize judged by Bryan Washington.

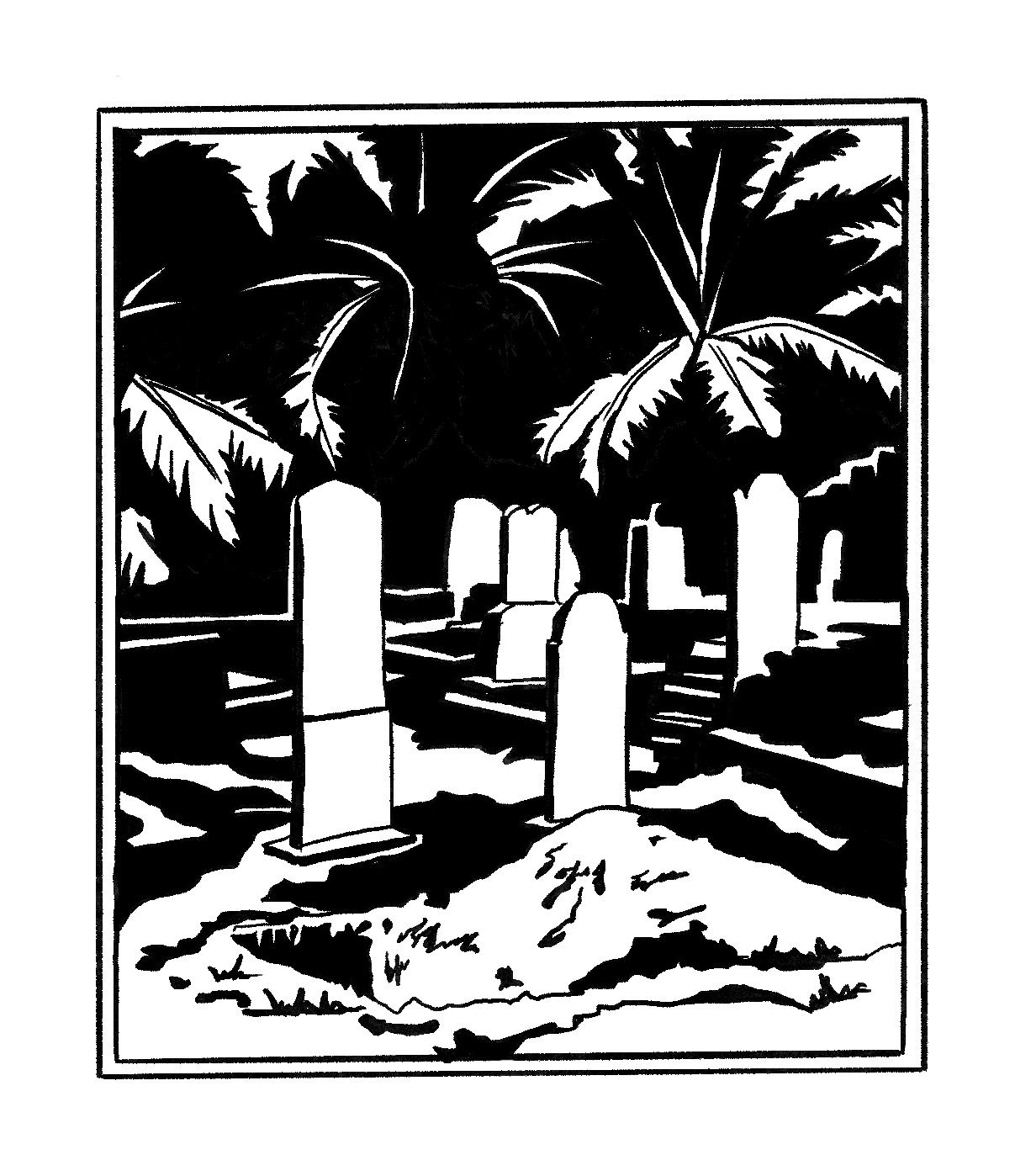

When we buried grandmother, we put her in the plot where mother buried grandmother, her uncle buried grandmother, and where my grandson will bury grandmother if he follows our instructions. We laid her to rest under a grove of young palm trees, grown tall amongst a dozen other plots, and between the third and eighth grandmother because it was bad luck to lay them in order, though we had forgotten where the rule came from. We marked each time grandmother was set into the ground with a funeral. No mourning, we sat and broke open a cask of beer as we talked about what her life had been, comparing it to the others as we waited for the rice to cook. We danced on the broken ground to flatten it back into the earth, although each plot was still rounded as though fresh and the soil was fine enough to fall between our fingers. We sifted through it as we tended to grandmother’s other plots. We pulled weeds, made new markers, and poured drinks onto the grave. Then we dispersed in the morning, hungry, having left the best of all we brought.

Months later, grandmother returned: my mother bore my sister ten months after the funeral. Though we hadn’t worried, we were relieved. Grandmother ruled us. She told us where to put up our houses and to plow our fields. She knew what was poisonous and what would fill us when our cassava spoiled in the ground. She had a cure for every illness, having died of each one herself, and entertained us with a never-ending cache of songs and stories.

Beyond her talents, grandmother was solemn. We didn’t bother her unless we needed something, or, during dinner, when we brought each of our dishes for her to taste. She used to sit where a beloved grandfather would, in the middle of the living room, her hands to her sides. Even in those final years when she was dying, we carried her there. All her children, some of them that she bore, others that she adopted, some that were her sisters and brother, came with problems: a neighborly dispute, a child’s education, a sore on the leg that would not heal. Having heard one or two lines of the story, grandmother would give her judgment, knowing more about us than we did ourselves.

I sat with her every day when she was firstborn. I carried her on my back. I watched for telltale intelligence in her beady eyes. I tried to take her to places that grandmother liked: the palms where she was buried, the back of the house to a bush filled with ube, the market road, and the Catholic church she’d helped to raise seventy years before. I held her up to see the faces of her daughters and granddaughters. She reached out to them and babbled, and we were satisfied that she remembered. As I remember, those were listless days–no money, bad drought, and instability. We became identical to our neighbors leaving town for the city and disappearing for years at a time. In the years grandmother led us, we stayed fat on what we grew and we kept to ourselves–no hostels, no factories built along our river shore, no school raised in the places where houses used to be. The main road hadn’t reached us, only went around. We had one dock, for the fishermen. Boats caught a glimpse of us as they passed. Traders, day laborers came and never stayed. Everything we needed was within the confines of the land, ringed by innumerable generations of grandmothers, always returning to protect us.

We thanked God.

When grandmother struggled to understand the farm, we began to worry. She was four. We asked her where to till and how we should irrigate and she met us with startling confusion. Mother told us to be calm. Before grandmother died last, her mind had been failing, so that she’d regressed into a baby, needing to be carried from the house to the hospital outside of town, where she finally passed away. We argued amongst ourselves when they were taking her. Grandmother had never left our town. And it was a crime almost, to try and preserve an old, sick body when she would return new and useful. By that time, grandmother had stopped telling stories. She stopped predicting the weather. She’d lost the ability to speak: if we wanted something, we did the work ourselves and grandmother would nod or point. Before she died, she was reduced to rapid blinking and by then, we were waiting for her to die so we could remember the sound of her voice. But my mother refused, screamed, shouted and we thought it all might bring grandmother grief. So we went to the hospital and came home with a coffin.

But then grandmother was seven years old and couldn’t tell wood from stone, never mind instructing us how to raise a foundation for a house. In the years it had taken her to start walking, we had many young people leave, and they came back with certificates and defiance. They surrounded our town with businesses selling imported goods, that we knew no better than to buy. We asked grandmother, but she had no opinion and asked habitually to be taken there because she liked to listen to the radio that played out of one woman’s store. Eventually, she begged to go to the school they’d raised, and since it was grandmother, we relented, shaved her hair, and sent her for the better part of a year. She came back speaking and reading in English, so we relaxed, realizing that grandmother meant to teach all of us, having foreseen change marching toward us.

Each year grandmother returned to school and came back with a new wish. A bicycle. A television. Electricity. These things we didn’t put up ourselves, but they came anyway with the influx of newcomers. With them too, the things grandmother did not ask for–a paved road, a cleared forest, a bar where grandmother began to skulk to in her teen years. Dizzy, we tried to interpret these changes like lessons. We read magazines about modern kitchens. I grew out my hair and permed it, coiffed it, put on short heels, and went dancing with grandmother at night. She drank and smoked cigarettes and leaned into me laughing. The room was careening. The ceiling was so low. Everybody danced close: the men on the women, the women on the women, the men on the men, and when she broke out of the spinning and the gyrating, she used my shoulder to steady herself, breathed, and reached into her purse for her own cigarette. She called it a camel, lit it, smoked it at the table, asked for a Guinness, looked at me, and asked for another. She cracked it open on her back teeth, clinked it against mine, and confessed:

I don’t believe that you believe. You all confuse me. She kept speaking, but she’d slumped over in a stupor. I had to carry her home. My mother and father approached me and asked if she’d spoken about our younger brother. They meant to send him abroad, as some men had begun to go, and to do it would sell the land and the plots where grandmother was buried.

She’s telling us to look into the future, they said, writing their hands. I shook my head and told them she hadn’t told me anything.

The only place grandmother still resided was the soil. Everything my sister did convinced us of this, first me, then my father, and one by one, the family around us, because my sister could not stop making mistakes. She got pregnant a few years after she discovered dancing. There were no less than three fathers because my sister went and found liberation the year we sent her to a teacher’s college. She came back and gave birth to a pale, sallow baby that grew up with thin, stringy hair and skin allergic to the sun. When that child was three, she confessed that the father was foreign and would never be seen again. We managed to save ourselves when we took it to the church, who I assume took it home to England. Thereafter my sister declared that she would never marry or have another child. She shut herself up in her room and declared a hunger strike, having seen it on T.V. We didn’t believe that it would last long. Unlike grandmother, my sister was lazy and slothful, slow to work or even move unless she was getting ready to leave the house late at night. She was an experimentalist, bringing back gadgets and sachets of whatever she could find from the city to try. She absconded regularly, which grandmother would never do, by bus and came back weeks later. Sometimes we would send my cousin, or brother, until he left (like everyone with promise did), to go and find her. She came back with shiny eyes, blue lids, and as of late, three missing teeth.

I could not stand the sight of her. She didn’t draw people to her side as grandmother did. Grandmother, who always managed to be tall and elegant, was replaced by my sister, who was squat, loud, fickle, and expensive, who spent all our money, who collected father’s paycheck at the end of every week, and had pushed my mother to work as a house girl (at her age!) to one of the new families now pretending to be founders of our town.

What were we left with? Nothing. Our crumbling houses, invaded by cockroaches the size of kola nuts, and our fetid front yards, sullied by a borehole that she proposed we drill. Our trees had been leased to a local palm tapping company, that, by way of a government official she’d seduced and spurned, had come to seize our land to plant more. The open sky above our property had turned into dense brush and at all times of day, we were plunged into the darkness. We ran a generator to keep the lights on at all hours and the smoke sooted out skin and we are sure killed three babies in my brother’s wife, so he fled with the first visa he could find. We pay to call him and he admits that he hates this country, because it’s dirty and black and useless, and we know our bodies are the land he scorns.

She had even ruined me, who never married, because my mother insisted that my sister needed a keeper. What, at one time would have been an honor, now made me a town fool, following behind her wherever she went as if to cry out to clear the road, my long face and my weariness louder than my voice: here comes our grandmother, clear, clear.

They were laughing at us, those people who used to gather at our step, waiting for grandmother to be wheeled out every night. They forget what she did for us for more than a dozen lifetimes. In forty years my sister had undone four hundred, dirtying everything with her hawing laughter, always in English, because all those years of useless school had snatched her ability to speak our mother tongue, and turned her into an idiot to rot inside her room.

She was there when our mother, the only person who still believed the grandmother had not been permanently lost when we took her to that hospital, died. If I were her, I wouldn’t want to be responsible either. Yet, I knew that she was, which is why even until her old age, she urged us to put our faith in my sister, as she’d put her faith in grandmother.

We knew mother was going to die for some months. Gout caught her. I rushed to marry an old man with three children who beat and spat at me. But he provided some little money for a coffin and a priest. We put mother in the family plot laid near grandmothers’, where no one had elected to be buried in years. We spent much of the day before, chopping away at the overgrowth, and breaking long clotted ground.

It was the indecisive end of the dry season and the sky couldn’t make up its mind whether to rain or not. We listened to the radio and made a nervous judgment based on the forecast. It was wrong, of course. By the time we brought mother, it was already drizzling.

My sister stood quiet throughout the whole ceremony, as the handful or so of us covered the ground. We’d managed to afford a few cases of beer, of which my sister drank half. And as we sat together, in complete silence, she burst into ugly song, her voice wavering and trembling with tears. My father, flattened into half his size, begged her for quiet, then my mother’s nephew, and she grew louder, and I could not see past her well-tended skin, decorated ears, and permed hair, so garish against the fading pressed shirt my father wore and the slippers falling apart on my feet. I launched myself at her. I struck her. And I was satisfied.

I sat back down, opened a Guinness on the side of the table, and watched her stare at us when it became clear no one would come to help her. She ran away, still braying, and as though a specter lifted, we were able to talk amongst ourselves, weary and soft, stories of my mother’s life.

When I peeled away from the guests, I went with a bag of fruit I’d taken from my husband’s house to leave for Mother. The ground was soft below me, breaking into pools beneath my feet. I pulled up my wrapper to keep it clean, but as I walked, specks of black mud jumped onto the hem of the skirt. The trees were heavy from recent rain, curling down to the ground, their leaves obscuring the markers of graves. Vibrant, moist grasses collected by the wayside, turning my entire skin soft and water-logged. The chill worked beneath my nails, shriveled my hands, and weakened my grip.

There was a sound coming from the site. I came closer. Singing. Shouting. My feet carried me forward: there was a hoarse voice, aged, an old woman. I wondered if maybe one of my aunts had made it here before me. I hoped no one would see me. I considered coming back another day, but curiosity got me. I entered the place where we buried my mother.

If you would believe me, this is what I saw:

My grandmother standing in my sister’s body. Her taut firm skim collapsed lips. Eyes filled with cataracts as thick as the bottom of bare feet. Ground down hands from ten thousand years of work. A back broken nearly parallel to the ground. A voice that carried a perfect sense of time. I figured, all my life, that it was how she remembered everything–a storyteller creating new lines with every illness she caught, every blight she avoided, and every journey she had taken before she came to our village because there were many, many years she spent wandering the earth before she turned and returned to here.

The sun tucked completely behind the clouds and she was a half smear of woman, diminished and fearful, swollen smile revealing tobacco stains and gaps where teeth had been.

She continued to bray. The song called out for pity. I could not bear to watch her anymore.

She bore no resemblance to us or anyone we knew. I could not say what she was.