Fall 2017

L: Four times a year, our printer deposits a mountain of

boxes in our front hall. We pull off the tape to get our hands

on the new issues, our glossy seasonal produce. Upstairs the

magazines are variously pored over, flipped through, tossed

on the ground, stacked on the tables, organized

chronologically one day and repurposed as coasters the

next. Every other cover bears a sticky purple ring of dried

wine like a bruise. Some of the boxes don’t get opened.

These migrate into a particular closet, and then, after a

decade, to a second closet across the hall, and then, at

twenty years of age, to the sad cement nook beneath the

basement stairs. Down there, dust and water form a paste

that glues the issues’ pages together. The ones that survive

stick around for a while: the rough paper of the early

Advocate’s pamphlets cohabitates in our bookshelves with

the smooth prismatic matte of the past decade. Our first

fifty volumes have retired to bound tomes. When we poke

through copies from the 90s, we imagine our predecessors

lounging around these very couches while we––the future

so-called collegiate literati––were napping in our baby

strollers. This fall, we’ve resurrected the glossy vibes of the

70s Advocate. Paper: slick. Spine: stapled. Content? Fresh.

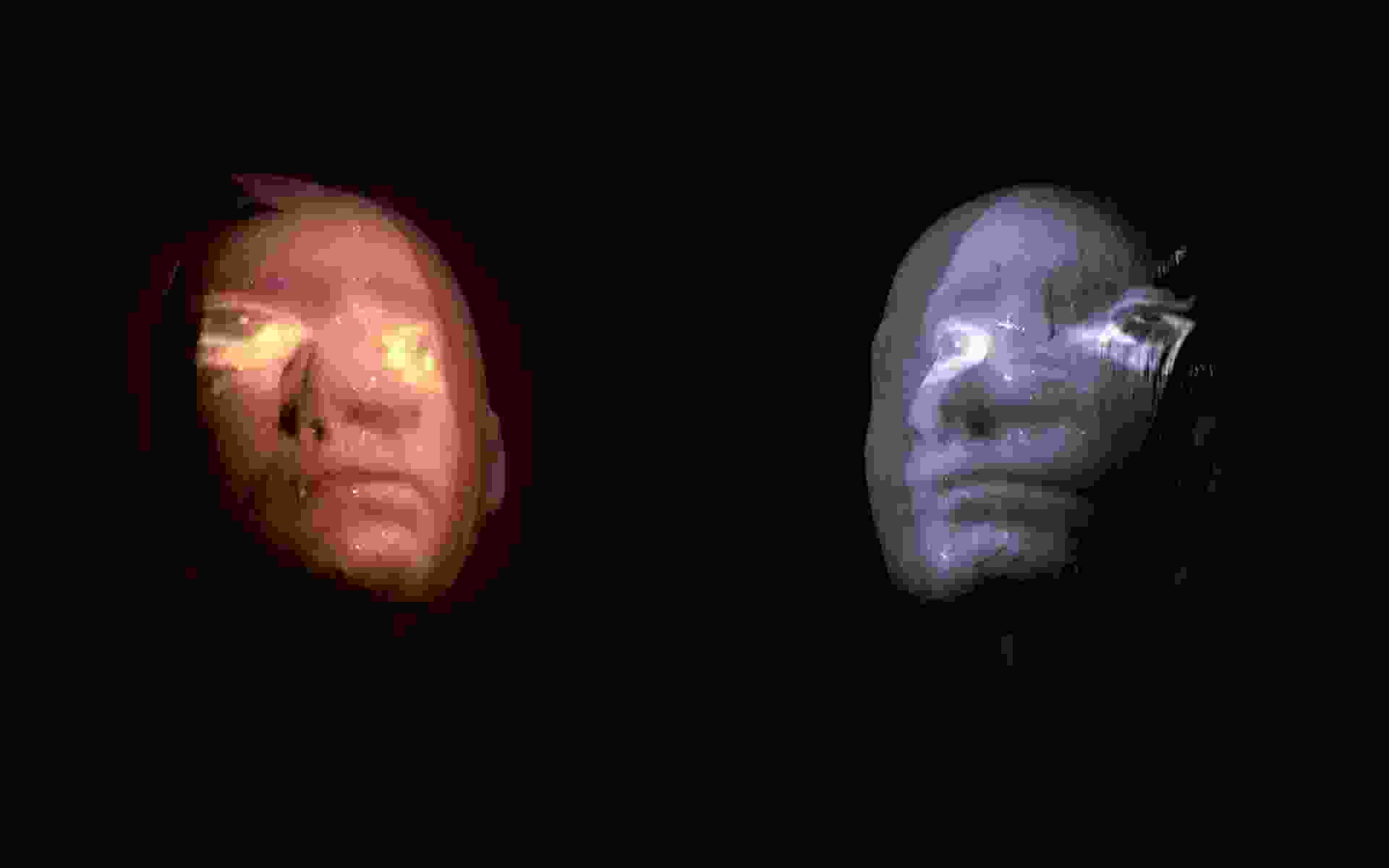

L: A naturalization of the eerie, or exposing of the sinister?

A fall from grace, or a courageous leap? Was it said, or was

it embodied? Cyclical motion, or an arrest of momentum?

New England autumn points ambiguously to mortality and

vigor in the face of it, toward the moral and the sensorial,

forward and backwards. In this issue, the light and dark

consider their changing relationship. The retrospective

is constructed, and the new smiles back uncannily. And

featured contributors Sarah Nicholson and Jorge Olivera

Castillo publish work, for which we are extremely grateful.

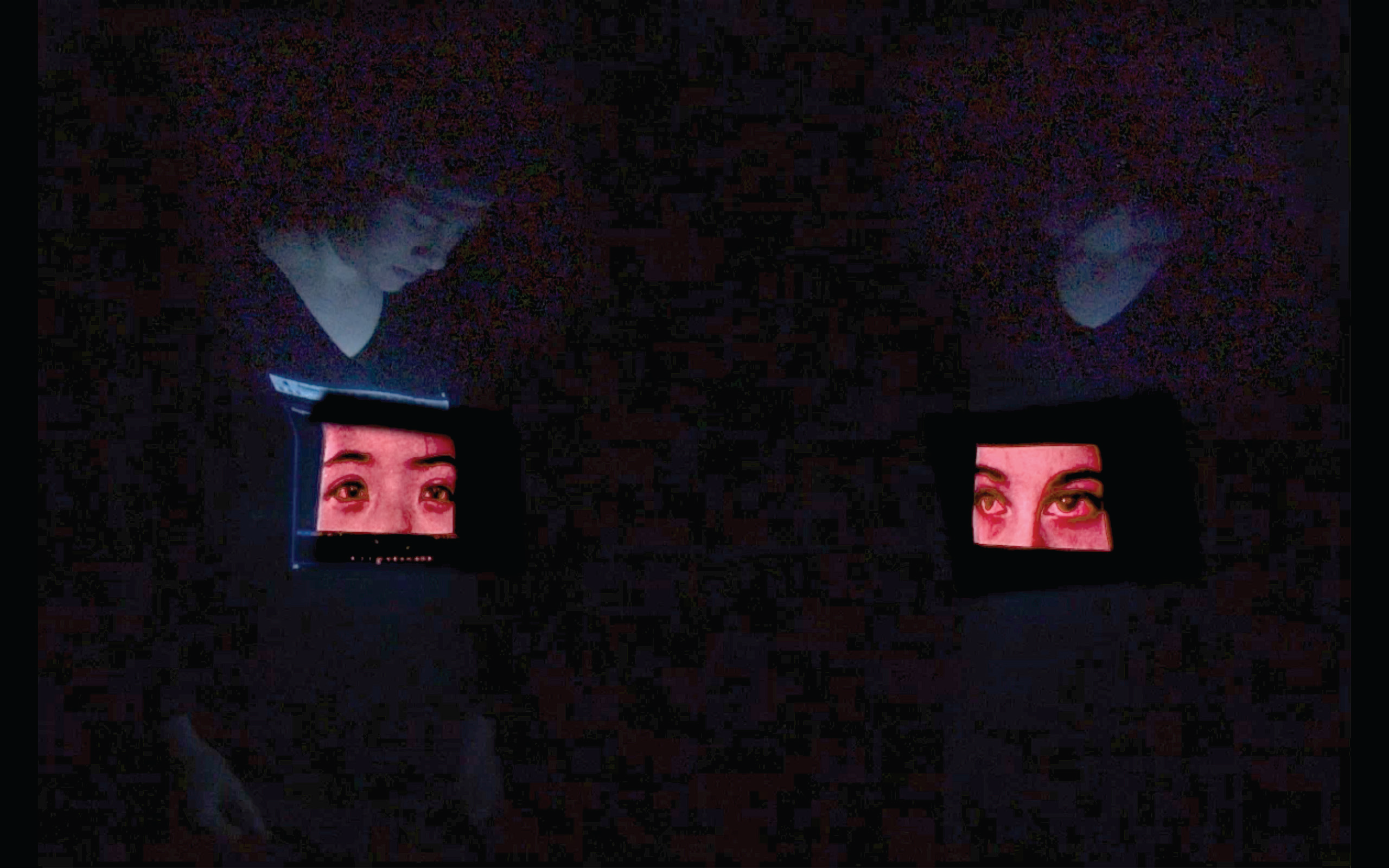

Winter 2018 - Noise

“In the age of media facts are generally defined by their signal-to-noise ratio.”

––Friedrich Kittler, *Gramophone, Film, Typewriter*

“Noise is the things that are not yet known, meaning that it is the future,”

––Hito Steyerl

At thirteen, my friends and I taped halves of ping-pong balls over our eyes and plugged our ears with white noise. If you denied yourself all sensory stimuli, we had read online, your mind would fill in the gaps, sculpting fuzzy audio and blurred light into all kinds of sights and sounds.

We needed the white noise for this exercise because ears adapt. When the room goes quiet, you start to hear the whirring of the air conditioner and the hums of lamps and radiators. You drag audio signals out of the sonic backdrop in order to have something to fill up your ear canals. Silence is relative––there’s always something more to hear. There’s a room somewhere in Ohio where they suck all the sound out, as if you could vacuum it up. Your ears adjust; you start to hear the behavior of your own organs. If you sit in there long enough, you’ll go mad listening to blood make its way through your body.

Since we’ve been working on this issue, I’ve been paying attention to the acoustics of rooms where people gather. In the Harvard Art Museums’ atrium, like in most atria, the ceilings are so high and the stone so absorptive that sound diffuses into auditory mist at a five-foot radius. The air feels thick with the cancelled noise of the conversation next to you. In every bar where you have to shout, you will eventually forget you’re shouting. There are quiet cafés where you feel yourself being overheard, where you can hear your voice striking the ear drums of others and it sounds terrible. Most restaurants play music to help you avoid this.

Noise lives a double life. It’s the random fluctuations in the background, where voices and images are born and where they go to die. It is also the car alarm, the lawnmower, the kid crying on a plane where you can’t get away and can’t make it stop. It tends to get between you and whatever you actually want to be hearing. “Noise is unwanted sound,” says the collective voice of Wikipedia’s legion of anonymous editors, speaking from the digital abyss.

These pages are home to a silent unwanted uproar. They are dedicated to sights and sounds neglected, to everything that reaches your eyes or ears but still evades notice. This issue of *The Harvard Advocate* tries to listen.

––Lily Scherlis

President

Winter 2018 - Noise

My first TV was the size of a microwave, with one of those bubble-like screens. It was relegated to the family Volvo after we got the new one (which was somewhat larger). My dad strapped it to a milk crate with bungee cords and permanently converted its signal to induction. It stayed there for years, lodged in the space between the driver’s and passenger’s seats. All of this so that my siblings and I would stay quiet on the five hour drives to my grandparents’ house in Baltimore.

We watched VCR tapes of Teletubbies reruns on those drives, long after it was no longer age-appropriate. There was something really weird about watching them watch each others’ stomachs light up, with the camera zooming into a screen within a screen, especially when that screen was someone’s belly. I was obsessed with the red one, Po, especially. This was during the era when food brands were paying royalties to put the faces of TV characters on their child-targeted products. For two years, I would only drink apple juice that had Po’s face on the bottle.

At my third birthday party a few years earlier, my parents had surprised me by paying a full-grown man to come strolling down our driveway in an eight foot tall Teletubby suit. While hiding behind the legs of several of the adults floating around my backyard in rapid succession as I moved away from this man, it occurred to me that the Teletubbies were in actuality men and women wearing eight-foot-tall suits. I had made an error assuming that their bodies, collapsed into the screen, were just my size.

PBS had duped me and all of my friends. I didn't care if Santa was real: the fact that Dipsy was actually substantially larger than my father seemed to represent a hairline fracture in the integrity of my personal universe. I was smaller than I had thought.

Besides: didn't my parents understand? I didn't want to meet Po (let alone an eight-foot version): I wanted, desperately, to be her. I wanted to belong to the world of green vistas and tubby-toast where the sun had a babyface and I had three technicolor friends who would hang out with me for 425 episodes straight. If my parents understood me, they would have carved a rectangle out of my torso and replaced it with a television screen.

***

I spent my freshman year of college trying to decide whether this deliciously narcissistic brand of desire where you want to become someone rather than to sleep with them was psychoanalytically legitimate. I took a queer theory course. My professor encouraged personal papers, so I thought I’d write about the time when I was thirteen and developed a massive infatuation for a movie star playing a sexy and mysterious doctor. She was female, and her primary character trait was that she was bisexual, a fact which other characters frequently mocked. *I want to be a beautiful intern*, I wrote in my diary in between eighth-grade science and eighth-grade math, forgetting the last syllable of “internist.” I made a spreadsheet detailing everything I needed to do in high school to get into medical school. I attempted to grow taller. I bought a dark purple nail polish, because the doctor often wore that color. “I want to be a closed book,” I wrote, and tried to develop a repertoire of facial expressions that communicated mystery.

“Listen,” said my professor quickly when I proposed this paper topic. “You like her because she’s a rich pretty white girl. That’s not especially queer of you.”

“*Liked*,” I corrected her.

My best friend Lucas was, at the same time, taking a course on intimacy more broadly. This one was mostly about straight people. His professor, who was a rich pretty white woman like my doctor, asked him to dinner after grading his final paper, but he turned her down.

Meanwhile, outside of the classroom, I was discovering whole new modes of intimacy through Lucas’ platonic presence. We spent most of 2015 at cafes dispensing nuggets of thought and memory for each other like Pez candies. I would put these tablets of information on my tongue and let them dissolve there. It was a good way to be friends. Each time he and I sat down to coffee, we both compulsively removed everything from our wrists and fingers. A certain kind of intellectual undressing for one another.

***

We say a relationship occurs between two individuals, as if it’s physically located in the space between their bodies. Affection is like some kind of invisible goop that fills out the negative space between two personalities, bringing the contours of each into sharper focus.

Joseph Beuys cast the spaces beneath brutalist German underpasses in hot beef fat, taking a perfect print of the empty space left by the cold fascist architecture in organic matter that refused to cool. Obviously my friends and I are not fascist infrastructure (at least I hope we aren’t), but I like to think of friendship as the tallow that fills up the cold gaps between us. It’s a warm metabolizing filling, a kind of adipose tissue that stores affection rather than glucose.

There's that classic Scott Fitzgerald line about how personality is an unbroken series of successful gestures. Sociality is a kind of a gaming streak. This line still raises my blood pressure. I’m still trying to get just one gesture exactly right.

Besides, he’s wrong. Personality is always a collaboration. Other people elicit the words and gestures that define us from our lips and our bodies. We spend a lot of time rooting out and chastising the social chameleons in our midst. Really we’re always, always, fitting ourselves around the shapes of other people, drawing our respective selves out of each other.

Moreover relationships of all stripes are nothing more than an ongoing sequence of collaborative gestures clumped into encounters, encounters that become a shared history, a communal lexicon of inside jokes and memories. Intimacy is when a language with only two speakers develops slang.

***

With my friend Castle there was never undressing. We did a lot of sleeping in his large bed together in pajamas, changing in the bathroom, trying to entangle (covered) limbs without leaving open the possibility of entangling ourselves. We wanted impossibly innocent intimacy from one another. Instead we spent a lot of time unpacking the insults his ex had levied at him before leaving. “I know I am not good at women,” he said. I guess we are a skill.

He had this way of making you feel like there were some people who were essentially worthy and some who weren’t, and that the more time he deigned to spend with you the more likely it was that you were in the former category. He knew how to make you feel special in the light of his attention, and to make you think he felt special with you. We were never dating and we only very occasionally slept together in the proper sense of the idiom, but he managed to get me hooked on an IV-drip of partial validation. Nonetheless I was feeling somehow both smaller and fatter by the day and we were quickly running out of television to watch side by side, and all the while his mother was slowly dying of cancer in another country.

The lack of television really did us in. Television was a way of avoiding eight hour debates about how to conduct our quasi-relationship. These were coldly aggressive encounters where we debated what constituted reasonable behavior toward one another in both theory and practice. If one of us gets hurt by the other behaving in a way that technically is not prohibited according to the terms of our relationship as presently defined, does that person have a right to be upset with the other? If I hurt you romantically, can you then reasonably deprive me of your friendship because I am not interested in you? Is one of us a sociopath?

We were trying to write a rule book while holding fast to the fantasy that what we had didn’t need one. “We’re not even in a relationship!” he would say incredulously every twenty minutes. “We’re not even really having sex!” I would say back. We both worshipped logic and verbosity as some common god of objectivity. “I’ve never argued with anyone so good at articulating their emotional reasoning,” he said once at 4 am when we ran out of steam and started pulling our verbal punches. “It means I have to be especially on my game.”

At first it was perversely fun to strain the emotion out of intimacy and hold whatever was left up to the light. And then we would strain out the emotion (which at that point was mostly anger and hurt) and be left empty-handed.

Television meant we didn't have to do this. We watched *Bojack Horseman* and *Friends* and *Rick and Morty* and *Game of Thrones* and *Big Little Lies* and *The Young Pope* and *Lizzie McGuire*. It was a way of spending time together without having to deal with each other. We could share the space of Hilary Duff’s mind without fighting. We could experience emotions together safely by proxy of the larger-than-life people on his laptop screen. Hating each other, we could be together in other people.

***

You try to get the people around you to hurt yourself for you, my friend Margot told me five hours into a Megabus ride. When you feel insecure you instigate these conversations where you try to corner your friends into verbally confirming for you that you suck. This is your worst quality.

Your worst quality is your tendency to calmly inform other people of their worst qualities, I told her.

I know, she said.

***

In my nightmares there's always a voiceover narrating why I am totally screwed. I think this is common, but nonetheless it’s remarkably disturbing to be informed of your imminent violent dream-death by a voice of authority only you can hear.

One time I googled “Dreams with voiceovers,” hoping Carl Jung would inform me in dense, comforting sentences that these narrators were doing the crucial work of integrating my conscious and unconscious minds. I wound up on a mental health forum for people who hear voices that aren’t there while awake.

There are three kinds of voices: the Narrators, who describe your behavior in the declarative, as if keeping a transcendent live studio audience posted on the situational comedy of your existence. There are Interrogators, who progressively nibble away at your confidence with intrusive questions, keeping you up late into the night. Then there are the Commanders. They give commands. “It is important that you stick to your normal pattern of doing things,” the forum says. “Otherwise it could cause you doubt yourself and Commanders might take advantage of your indecisiveness.”

In a section titled “There is Hope,” we are advised to not stay silent:

If a voice is harassing you, you could start by calmly but firmly stating, “I hear you. Thank you for letting me know how you feel. Right now, I need to [insert important task] but I would like to discuss this matter with you later.” Then make a time and keep it. Keeping your word will become very important as the relationship grows.

It could be worse. I could have to reckon with dissenting parts of myself out loud, to make all of my internal conflict manifest sonically.

***

Lucas and Margot didn’t approve of Castle. They didn’t get why I continued to spend time with him when the six-hour verbal boxing matches left me badly existentially bruised.

I didn’t get it either. I was starting to feel like I was playing a fighting video game where my avatar had a special maneuver called "consider your thoughts and feelings and life decisions from an outside perspective." This was one of those moves that has to charge up over a period of time and then you get to do it once and there's a cool cut scene where you watch your opponent (my demons?) get shredded to ribbons or whatever. The move was my avatar's dynamite and without it this avatar was totally useless, limp, subjected to the facile violences of its opponents. And here I was with Castle, mashing on the controller, hitting the combination for "consider your thoughts and feelings and life decisions from an outside perspective" again and again, but the move hadn't sufficiently recharged.

Seven months later the console stopped glitching and I blocked his number.

“I miss you,” said Castle in an email a few months later, “And I want to know if you cried at the end of the second to last episode of the new season of Bojack Horseman like I did.”

***

I spent the summer when I was eighteen running around the Nebraska prairie with a gaggle of feminist artists. I bleached the tips of my hair and started wearing bandanas. On the prairie we were trying to learn to capture beauty and keep it. Everyone wanted to work with the figure, so we all had to take our turn as the model.

The first time was the hardest. “Here,” my photographer-to-be said, pushing her laptop towards me. “You can see my body before I see yours.” On the screen were a series of images of my new friend reclining nude around a tastefully decorated apartment with a glass of wine and a coy smile.

Earlier, she had shown me black and white images she had taken back in Tel Aviv. Her friends were anonymous bodies, leggy and well-crafted women who stared past the camera. They smoked hand-rolled cigarettes, easily folding their bodies into strong lines and pleasing arcs.

I had short legs and razor-burned knees. I smoked my first-ever cigarette a week earlier and hadn’t liked it. I cared, a lot, about what other people thought of me and my body and what I thought of myself and my body, and about making sure no one knew this. I also had this idea that I could be the kind of person who would agree to model naked without hesitation. My new friend made me feel special, like I too could be a striking twenty-something Israeli-American journalist with a fascinating sex life.

I thought she was beautiful. She was calloused and well-spoken and certain of her right to take up space in the world. She had been a drill sergeant in the Israeli army, spoke Chinese, and had once tried to illegally cross the Nepalese-Tibetan border alone on foot. She focused on you with sharp eyes and surprising warmth and never made small talk.

She said she prided herself on her ability to show her models the beauty of their bodies, and I wondered if she thought I was pretty. I was worried about bruises and scars and hairs. I thought about what underwear I would wear as if she was somebody I hoped to sleep with.

She handed me whiskey and loaded the film into her outmoded camera. Later I would nervously knock the empty copper cup out her window. “Ready?” she asked.

I wound up hating these images of myself. I had hoped that teaching myself to strip on command would teach me to be comfortable in my own skin, an expression which always gives me hope that my skin is a thing I could maybe someday get out of. I didn't trust mirrors for a minute: they all told me different things. I hoped photography might pin down a single and absolute image of my body, which I could then interrogate once and for all: are you beautiful? In reality, the photographs were as fickle as the mirrors. You would question the images and they would smile back and say what do you think?

***

When you draw a naked body from life you're supposed to look at the negative shapes––the curved quadrangle comprised of torso, upper arm, forearm, the hand meeting the hip. The swoop of the neck, when your visual field is flattened into two dimensions, makes contact with the straight line of the by the window pane behind. Only the spaces between body parts are impartial: we have so many laden expectations about the ways bodies look that they interfere with the way we see them and then we can't draw them right.

Various friends of mine have been employed as life models for figure drawing courses. “I feel like I’m professionalizing my ability to be vulnerable,” one of them told me, which happens to also be how I feel about writing. But in reality the life model becomes almost entirely desensitized to his or her nakedness. It’s strenuous work, holding a position. You pick up the skills and then nudity is a kind of a clothing: you are doing your job. It’s not that vulnerability has become banal, it’s that the pathway to vulnerability nudity once provided has closed. Your skin has become an impermeable cover stretched tightly and securely around your self. There are no gaps: you can be all surface.

Confronted with such a surface, we infer the presence of something like us somewhere in there from the behavior of cloth and skin and eyes and invisible vocal cords. We accumulate evidence of interiority, collecting gestures which we connect like dots to approximate what someone is like, how they experience themselves, how they experience us: who they are, really.

We’re always making these predictions, trying to hone our prediction-machines into 99.9% accuracy. We want to achieve knowledge of someone, which looks a lot like intimacy. We want to arrive at a place of absolute comprehension, to reach through our companion's sternum and pull out a struggling wet bird-like organ, the atom of their personality, which we can then hold in our hands and examine (or better yet, X-ray it, sequence its genome, dissect it, bring it to show and tell, and then maybe sew it up and put it back for someone else to check out later). We want to say, "Oh, that's what you are," and then possess that information permanently.

I used to wish for a concrete end to the process of getting to know someone. I hoped for a grand finale to the scary undertaking of progressively revealing the authentic and easily bruised pieces of yourself. If you peel back enough layers of tasteful clothing and casual charm, maybe you find a core nugget of individuality, the atom of the personality. Or maybe there will be nothing left.

***

Lytton Strachey and Dora Carrington were in love, kind of. Their relationship was dramatized in a 1995 Emma Thompson biopic that focused mostly on Dora. It was subtitled: “She had many lovers, but only one love.”

In addition to a lover, Dora was an underappreciated painter. She went by her surname and had a pageboy haircut before its time. All the boys and girls at art school were at in love with her at one time or another.

Lytton was a member of the Bloomsbury Group of artists and writers. He was also gay. In the movie he met Dora at a house in the country in 1916 and thought she was a boy. He was disappointed when he found out she was not, but they moved in together all the same. Then Lytton fell for a man named Ralph Partridge. Ralph fell for Dora, and she agreed to marry him to keep the three of them together. Lytton died in 1932 and Dora committed suicide the next spring. Lytton, the world learned in 2005 from some letters, was a sado-masochist.

They say Virginia Woolf based the character of Neville on Lytton in her play-novel *The Waves*. There’s a scene I love where Neville and his best friend Bernard are quarreling. Neville sees Bernard walking up to him and starts to thoughtfully chew his metaphysical cud:

How curiously one is changed by the addition, even at a distance, of a friend. How useful an office one’s friends perform when they recall us. Yet how painful to be recalled, to be mitigated, to have one’s self adulterated, mixed up, become part of another. As he approaches I become not myself but Neville mixed with somebody—with whom?—with Bernard? Yes, it is Bernard, and it is to Bernard that I shall put the question, Who am I?”

It’s a novel where everyone’s always thinking at everyone else, speaking to each other without actually speaking aloud. Woolf hops between the insides of their respective heads:

Bernard: You wish to be a poet; and you wish to be a lover. But the splendid clarity of your intelligence, and the remorseless honesty of your intellect... these qualities of yours make me shift a little uneasily and see the faded patches, the thin strands in my own equipment... I become, with you, an untidy, an impulsive human being whose bandana handkerchief is forever stained with the grease of crumpets.

Neville: I hate your greasy handkerchiefs—you will stain your copy of Don Juan. You are not listening to me. You are making phrases about Byron. And while you gesticulate, with your cloak, your cane, I am trying to expose a secret told to nobody yet; I am asking you (as I stand with my back to you) to take my life in your hands and tell me whether I am doomed always to cause repulsion in those I love?”

Neville doesn’t get his answer, and, pissed off, hurls his poem in Bernard’s direction and leaves the room. Bernard thinks to himself, simply:

“To be contracted by another person into a single being—how strange.”

Winter 2016 - Danger

I was out of shape when I showed up. I had kind of thought I was done. I had already made it through the hoop that counted, the admissions hoop. I had stuck my landing; now I could relax. They don’t tell you when they accept you that hoop-jumping is the official sport of the College. Especially at the beginning, I had this sense that I was in fact a hoop-jumping recruit, a scholarship kid. I had to keep jumping to earn my spot here. I would later talk about the sport in terms of the fix: that dopamine rush as your toes have cleared and you realize *you’re through*. In those first monthswe were all obsessed with recreating the experience of that first successful jump.

You get the sense that you have to join a cult to make it here. There are a lot of options for what cult to join, but you have to join *one* or you’re never gonna have a Real College Experience. Unless you have really great roommates. If you have really great roommates, you’re exempt.

To join a cult, you have to jump through that cult’s hoop. When you meet people here, you look at their bodies. You look at what muscles they have where, whether it looks like they could make a particular jump.

The cults recruit every semester. They run training programs that last most of the semester and culminate with the Jump where you either make it through the hoop and into the cult or you don’t. Sometimes there is a preliminary hoop that happens halfway through training, and if you don’t make it, you aren’t allowed to try to make it through the final hoop that semester. Every cult has its own hoop—different shapes, different heights—and each training program is tailored specifically to the cult’s hoop. Sometimes training for one can make it very hard for your muscles to learn to jump through a different one. Some hoops are easier for certain body types.

It’s a big deal. At the very end of College there’s always the prestigious Hoops prize which I think is for the senior who has jumped through the most hoops. If you get that you can do whatever you want. Then you definitely don’t have to jump through any more hoops.

I knew pretty early on which cult I wanted to try out for. I went to the Intro Training meeting. I was shaking a little bit when I walked into the culthouse—it felt important and intimidating, like the very wood was charged with gravitas. I looked at all the older affiliates and thought they looked much cooler than me. They were sitting around a heavy wooden table, with the Big Kahunas sitting in the middle looking important, looking out at us. All the jumpers were on the floor. All the affiliates spoke with the same cadence. Perhaps they spent so much time around each other that one had adopted another’s distinct manner of speaking in turn until everyone spoke with the same unified nuances. This was true of a lot of the cults: You could tell who was in what by how their voice sounded. All these affiliates made it through the hoop, I thought to myself. This terrified me. I imagined their bodies tensing up with nerves, sprinting and vaulting and *clearing the hoop*, muscles taut. I imagined the smiles on their faces when they stuck the landing. Some of their bodies had since gone to seed. Once you made it through the hoop, I guessed, you didn’t really have to stay in shape. You didn’t have to worry about much at all: In a cult, you had it made. People *respected *you.

At the training meeting, we watched all the old videos, in which famous old affiliates, long graduated, cleared the cult hoop with *style*. I felt my toes pointing in my boots. I was anxious to prove myself. I was on *fire *with it. At the end of the meeting, the Big Kahunas looked at each other and took the big group of us jumpers into a small locked room in the basement of the culthouse. We were all huddled in the doorway—I went up on my tiptoes to see over the group in front of me. And there it was.

“Of course, it will be higher,” said the Big Kahuna. It was old and made of a warm brassy medal and extensively engraved. It was a small hoop—not more than three feet in diameter—but I heard they kept it relatively low down. This was good, because I was not very tall. It seemed like it would weigh a lot and hurt a lot if you messed up your jump and crashed into it. I looked back at the other jumpers. They were all shiny-eyed. Some of them were already in very good hoop-shape. I was going to have to train very hard, but I really wanted it.

I spent long hours doing the calisthenics the cult’s trainer recommended.

There are rumors that affiliates lower the hoop for jumpers they like, for jumpers who look like they would belong in the cult. I didn’t know whether to believe them or not, so I tried to dress like the affiliates and try to get the cult trainer to like me, just in case it helps. I got to know some of the other jumpers during our training sessions and we would laugh in hushed voices about the vocal tics of the cult trainer or the Big Kahunas’ pretensions during the Intro Training meeting. I felt connected to these other jumpers.

A couple days before the preliminary hoop, I cried over lunch with an older friend who had cleared a number of well-respected hoops. Sometimes around here it feels like everything's about who's jumped through what hoops. I asked why we even needed cults. If there were no cults, I told him, we could just*spend time together *and get to know each other in the normal way and not spend our time sniffing out who was worth knowing based on what cult they were in. He nodded patiently and told me that all of these things had occurred to him when he was a young jumper. This complacency made me terribly angry: Once you were enfranchised, once you were in, there was obviously no motivation to do anything about it. I imagined myself, suddenly, years down the line, a complacent affiliate, watching all these freshmen making the jump they’d trained for months for and missing the hoop and knowing they would spend another semester on the outside. Don’t let me be that person, I told myself. A small voice said, *But if you make it, of course you will be. *

I made it through the preliminary hoop, which was just like the final one but larger, easier, made of a flimsier and more forgiving material, and kept training hard. I watched my body change. I woke up to aching muscles I didn’t know I had. I dreamed about that final hoop. There it was, dusty, winking at me from the basement of the culthouse.

Final hoop day was less of a big deal than I thought it would be: They hauled the thing up into the big main room on the second floor of the culthouse and you waited in line until it was your turn to jump. You made it through or you didn’t, and then you landed.

When you're looking at a hoop—even a low hoop, even a hoop that everyone makes it through eventually—you're thinking a couple of thoughts. You're thinking that this hoop is the measure of your worth as an individual. You *know *that this isn’t true—you know that there’s a lot of chance and variables you can’t control that go into whether you make it or not—but you inadvertently can color the result as the ultimate reflection on your innermost self. Do I deserve this, you’re thinking, or you’re not, because you’re focusing too hard on the jump itself.

I made it, and I stuck my landing, thank god. The cult trainer and a couple of other affiliates marked notes on clipboards. A Kahuna carefully measured my final distance from the hoop, which was discouragingly small. Other jumpers had jumped further. There was some polite applause, and I was ushered into a room downstairs to wait with the other jumpers who had made it.

Because I was a freshman the cult swallowed me pretty cleanly—I didn’t have many strong attachments. After I became an affiliate of my cult, I saw those other jumpers—the ones I’d gotten to know who hadn’t make it—around the College. They didn’t really want to talk to me. It was okay: Suddenly I had a place to go, somewhere I felt a little bit special every time I walked in the door. The culthouse felt like it was a place of magic. It radiated out from the hoop stored in the basement, permeating everything we did and said inside the culthouse. I felt lucky to be a part of all of it.

A week or so after I made it through the hoop, a Big Kahuna mused that he was jealous: He wished he could be a new affiliate again. I stared at him, wide-eyed, and asked why he’d ever want that. Big Kahuna smiled and said that as a new affiliate, everything felt so magical and shiny and new. Over time, he said, with more responsibility, the magic wears out. I have a song for you, he said, and hooked up his phone to the speakers to play a song which repeated a single lyric to an infuriating beat. “You can normalize,” a voice said over the sound system, “Don’t it make you feel alive?”

I thought about that glowing hoop in the basement. I couldn’t imagine normalizing any of this. We have this notion that we can reach out and grab the self-assurance of affiliation and hold onto it forever. Really we can only take validation in doses. The feeling always fades, and then you need a little more. You find yourself another hoop, but there are always diminishing returns: Suddenly the same dosage won’t do it for you anymore. It’s like when you get stronger and suddenly the ten pound weight doesn’t make your muscles burn. You get something heavier. It seemed like if you wanted to feel like a real part of the cult, you had to be a Kahuna.

Becoming a Kahuna meant another jump—this time through the separate intracult hoop, which was a different deal entirely. This one was very large but was some kind of a polygon, a scalene triangle, they said, so it would be easy to guess the angle wrong and get stuck. The Kahuna hoop was set out annually and the jump was set to happen about a month after I became an affiliate. Luckily for new affiliates they kept the hoop pretty low. (It was higher, of course, if you wanted to be a Bigger Kahuna). I was still in good jumping shape and made it right through.

As a little Kahuna, I had new responsibilities.

I could play my own music over the speakers in the culthouse. Suddenly I couldn’t hear the different cadence in the voices of the Big Kahunas and couldn’t tell if I’d adopted it or not—it just felt normal. At first, cult-ural acclimation is confusing and weird and stilted, and then it’s natural, and then it’s just like breathing, and then you can’t imagine *not *doing those things. You can’t remember a time when you didn’t know to play this song or drink that drink. I *was *starting to normalize. There is something really satisfying about feeling like a part of a place just by knowing its little customs.

But that humming golden hoop in the basement just felt like an old hump of metal. For so long I had felt I was catching a glimpse of something furtive and beautiful that belonged to all of us, partaking in a set of customs and aesthetics decided by a Big Kahuna long ago. Now, another little Kahuna and I would play a certain song and then someone would ask for that same song a couple days later. We could do things that had never been done before, and affiliates might like them, affiliates might do them with us.

This was exciting, but it was also hard to be in awe of something we were making. I wanted that reverie back.

Suddenly I was on the other side of the Intro Training meeting. I was very conscious of this reversal, but it didn’t really feel like a big deal. It felt hollower from the other side: The affiliates at the table were all familiar faces. I wondered if we seemed intimidating and cool to the jumpers. I couldn’t imagine we did. We were just goons.

I was put in charge of training a couple of jumpers that Spring. I turned to older affiliates for training programs and held as many extra practice sessions as my jumpers wanted. I cared about them. Not one of my jumpers made it.

And then there are the would-be affiliates who were told from a young age that hoop-jumping isn't for them. Their bodies weren't built to jump through hoops, affiliates used to think. Moreover, maybe the hoops weren't made to allow their bodies through. This is a complicated problem which can't always be solved by changing the shape of the hoop (the shape of each cult's hoop is sacred, so sacred). From the inside, I badly wanted to believe that mystique and inclusivity were not mutually exclusive.

At the College, the absence of a cult can feel like a deep insecurity that leaves you open to a kind of death: the death of being just like everyone else. Or at the very least, it’s like being the only vegetarian at a BBQ restaurant or the non-smoker on the smoke break, except instead of cigarettes we’re talking about achievement-crack. I admire these people who do the College without it.

Sometimes I worry that one day I will be old with all of the spoils of my hoop-jumping career sitting around me and wish I had spent my life on something other than the stupid sport. I consider the arthritis some long-term hoop-jumpers get from the repeated exertion. I’ve already had one bout of this arthritis.

But the spoils can be sweet: the feeling of communal self-worth; a kind of special inclusion in something magical and secret; a humbling sense of one’s own privilege to be a part of the group. I think some of it also really does come from all those good things we talk about in our pre-jump speeches: from having a community in which to invest your energies, a thing you have come to care about altruistically, for its own sake. The big old world, from inside of a cult, was whittled to a manageable size.

I don’t think they’re mutually exclusive—the community-mindedness and the validation —but I worry that the latter is addictive.

I decide to go for a bigger hoop. A lot of people expect that I’ll have no trouble making it through—I’ve never missed, have I? I’ve done a lot for the cult and the Big Kahunas will recognize that and put the hoop lower.

I don't make it through the hoop. A tie on my jacket gets caught on one of the odd polygon’s corners and I hang there, half in half out, for much too long before they figure out how to get me down.

People normally don't get stuck. When they take me down, everyone’s sympathetic. It’s okay, they tell me. We’re still your family.

The other little Kahuna makes it through and becomes a Big Kahuna. I feel a little bit left behind, and then again, I’m happy for him. I’m happy for the cult; I know he’ll do great things as a Big Kahuna. But I’m sad that I won’t get to do them with him. I didn’t know how to look at this: The cult was in great hands, but those hands weren’t my hands. It didn’t need me.

These things are really fucking messy psychological experiences. They never sound good politically: In this article, I inevitably come across as overly ambitious or a traitor to my cult or allegiant to a problematic power structure. We talk about all this in such sanitized terms: Are cults objectively *good*, or objectively *bad*, for the College community as a whole? I think the real answer is much more nuanced—the structure as it is has oscillated between giving me a home and a sense of magic and breaking hearts (mine, others’). My time as a jumper and then as an affiliate and then as a Kahuna—an absurd trajectory which is completely illegible outside of the College—has given some meaning to my subjective and individual experience. I think there are conversations about these groups that aren’t making it into the discourse (the politically-incorrect, subjective, biased experiences of people inside and out, which get sterilized into strong political statements). I think we too often conflate ambivalent subjectivity with emptiness, uselessness.

Let’s end with a tally. I have gratitude for the strength I gained from jumps, successful and not, and gratitude for the family the hoop gave me. I worry about the way that love for the sport itself can tear this family apart. I worry about cult-ures of exclusivity and the lines (perhaps arbitrary) they draw between the inside and the outside. We dance across these lines (which make all of us uncomfortable, inside or out) with buzzwords like “inclusivity” and scathing op-eds and small acts of kindness toward our hoop-trainees. I think there are fulfilling ways to be in and around this cult-ure without hoop addiction. I am still trying to find them.

Fall 2015

Nebraska is a sea of land–flat and stretching in all directions like a Monsanto ocean. At dusk, hot orange radiates a full 180 degrees along the horizon. We are here to work, to raise this season’s crop of art, which will be fully organic, insufficiently subsidized, and only half-ripe when they cart it off to market.

I live with four artists—Raluca, Z, Lindsay, and Aimee—in a house that hardly even qualifies as a building. The living room is on the second floor, or the first depending on the part of the house you ask. There are leather recliners and floral couches salvaged from all over eastern Nebraska and an ancient heater. “Sassy Nebrassy, you’re one classy lassy,” someone has scribbled on the wall, “May I put my silo in your chassis?” A constant stream of moths floats between the single naked fluorescent light, and the great wilting marijuana plant hangs from the ceiling. (A hex on the fauna, says Z, but if you touch it after dark a veritable cloud of insects you didn’t see will abscond in a rustle of wings and leaves). We roll great dried leaves into amusingly weak spliffs and take big drags in the second floor studios. The freezer is full of Tupperware containers of eggshells and squashed grapes and wilted spinach. The sink has stopped working. At night I climb out one window or the other onto the still warm tin roof and try to feel things about the stars. The house is named Victoria and has a life of her own.

Vicky, having more holes than walls, makes you wonder about the difference between inside and outside. She is leaky and lovable, mother to generations of budding artists, a family of raccoons, a menagerie of birds and snakes and mice. She has a door on the second floor that opens into thin air. She has no foundation at all and can’t protect us from the incoming tornadoes, but she can protect us from ourselves. In a week, the dusty film on your skin and the bug bites are comfortable staples.Their absence would feel disorienting, sanitized, inauthentic, like too-white teeth.

They call this a residency. We work for three hours a day keeping the farm in good shape—putting in shelves, unclogging drains, moving a barn ten feet to the right or a house five miles to the west. In return, we get free accommodations and studio space. I meet Ted, the guy in charge. He has a habit of quietly turning up behind you unexpectedly and then evaporating into thin air. He stands at six and a half feet and speaks softly and sparsely, as if compensating for his massive physical presence. It takes two days for me to notice he’s missing half a finger. “Don’t ask,” someone tells me. One of the other buildings on the farm was supposedly his childhood home, a leaky frontier house with something mysteriously called a “birthing room” where he may or may not have been born.

While we work, Ted mumbles instructions under his breath, ominous things like “use the table saw,” and, in one worrying case where I got a brown fluid all over my hands while rewiring a lamp: “that chemical causes nerve damage.” When I stab a rusty nail halfway through my thumb, he plants me in a very comfortable chair that looks like it was salvaged from a minivan and calmly pours out the rubbing alcohol. Ted is all quiet experience— standing in the shadows of the barn behind us, always carrying the right drill bits in his pockets and giving us the right tools before we know we need them. None of us has much experience with construction, but he forgives us when we screw up time and time again. He forgives us when we fall off roofs, get arrested stealing hemp plants from other farmers’ fields, when it takes all eight of us to carry a twelve-foot beam. “When I was thirteen,” he whispers to me, glowing, “I could carry two of these a mile by myself.”

***

Last September a friend and I went on a day hike in the Blue Hills outside of Boston. We had no cars, so we took the subway and then the bus, which dropped us off a stop too late on the side of a highway. We began our hike trekking through parking lots and under overpasses, with monster hotels like trail-markers, trying to find the safest way to scale a clover junction. “No one has ever loved these spaces,” my friend said. She could very well have been right. For the roadtrippers and commuters driving through, it’s just another gas stop on the way to somewhere else. Employees at the hotels and restaurants probably see it as just another 9-5, a stop en route to the American dream where you can own a chain of these joints and never have to actually come to places like these.

This is why the farm was so special. The corn is a sea, and the farm is an island, an oasis of cathexis in a big world of nothing. These days you hurtle through the sky in a metal canister, disappearing from somewhere and plopping down somewhere else. You can drive, and the highway stretches for eleven hours, eight days, three months, but do you feel the distance from the raised interstate, the channel from A to B, lifted up and over everything in between?

Are you ever really anywhere? The states are full of neutral buffer-zones, airport terminals, strip malls, the kind of anonymous territory that could be Anywhere, USA: Huffington News, CVS, TGI Fridays, Au Bon Pain, Brookestone, Home Depot, JoAnn Fabrics, Walgreens, Subway, Kohl’s. You tell where you are from the local variations: Pittsburgh has the supermarket chain called Giant Eagle; I hear rumors of something called a “Higgly Piggly”; Nebraska has a fast-food chain called Runza that sells what are basically the mutant children of corn dogs and hamburgers. Middle America has a lot of sincere enthusiasm for the suffix “and more.” Waffles and more. Espresso and more. Corn and more. Life, and more.

***

Here in Nebraska, Monsanto is a local god. It brings the seeds that germinate and, year after year, turn magically into corn. It brings the chemicals that rescue that precious crop (and the American economy) from pests and demons. Monsanto is a god of science, of progress. Bigger, it says, and better: more ears to fill more mouths, better genes to fight better pests. Life scientists are engineering soybeans that deliver omega-3s to fight heart disease, nutritionally enhanced broccoli, disease-resistant vegetables. The rhythm of life: sow, till, harvest; every four years pull out the nitrogen-sapping corn and plant soy to restore nutrients to the fields.The irrigators—raised, snake-like metal structures on motors and wheels—crawl through the fields of their own accord, forward and back. From our vantage point, the corn seems to grow itself.

Non-believers say the name like a curse. You hear those three syllables whispered in the car, speeding through the infinite grid of corn and soy.Their accusations: Monsanto “plays God,” meddling with things that oughtn’t to be meddled with. Monsanto Corporation has a long history as a civilizing force. The word culture itself comes directly from crop cultivation. A chronological survey of ominous-sounding products: Artificial sweeteners morph into PCBs which become plastics, Agent Orange, bovine growth hormone, LEDs, DDT, and most recently, the herbicide glyphosate and corresponding glyphosate resistant seeds. Their products work hand in hand to give life and take life away, two processes that in modern day agriculture are all but inseparable. I’m reminded of the plethora of mythologies where the god of fertility is also the god of death. Culture, specifically monoculture, will triumph over nature—but are they really that different?

The problem is that plants aren’t docile. We underestimate anything rooted to the spot. Plant genes, encased in spores and pollen and the like, are meant to move because plants can’t; plants can change rapidly, genes crossing from species to species and flowing wildly. Even monoculture crops don’t exist in a vacuum. Genes for pesticide resistance can flow into weeds, like viruses that develop resistance to antibiotics, breeding aliens from within. There are stories of invincible horsetail weeds eight feet high. Farmers react in the only way they know how—by spraying more, which only breeds bigger and badder monsters.

Monsanto isn’t omnipotent, but it is pretty damn powerful. Of the corn planted in the US, nearly three quarters is genetically modified and controlled by Monsanto. There’s corn for ethanol-based energy, corn for animal feed, corn for human feed. When you include calories from corn-fed meat products and corn syrup, it’s easy for a majority of your bodyweight to be composed of re-purposed corn. There’s a lot of money flowing around the industry: money to farmers, money to corporations like Monsanto to make crops cheaper to keep people buying them, too-big-to-fail money flying this way and that, money for corn-based energy to ease our dependence on oil.

Here’s how this looks if you’re a farmer: organic agriculture is labor-intensive and expensive. The more you produce, the more you get subsidized, so you get paid more per pound for more pounds overall. So you go big or you go home: You pick crops that promise enormous yields, you band together, you grow big crops on big acres. You buy

more seeds and plant more seeds and use more pesticides to prevent more crops from more pests. Farms merge into other farms, and the heart of the states becomes one great Monsanto ocean where you can’t tell where one farm ends and another begins. The seeds themselves are copyrighted as intellectual property, and Monsanto is known to sue farmers who replant seeds from last year’s crop to avoid purchasing new ones. Their license to use those seeds has expired, so to speak. Monsanto is working to bring “Terminator” seeds to the market—seeds which effectively self-destruct after a year, automatically enforcing the licensing. The big fear is that Terminator genes, in a plot twist eerily reminiscent of the film franchise, will flow into conventional and other crops, assassinating plants of all kinds and wreaking havoc on ecosystems. But hey, intellectual property is intellectual property.

The thing that worries me the most about monoculture is how it edges out complexity on both ends. Advocates of Monsanto are fiercely defensive, perpetuating a rhetoric of better plants, stronger plants, feeding more people. None of the concerns have been adequately proven, they write. Don’t bite the hand that feeds you. Critics talk about intense political pressure to suppress the science, of potential famine and farmers struggling under legal bondage to a corporation that charges more than they can afford for the only seeds they can grow. And everywhere is an either/or: You pick one creed or the other. Either the corporation is the benign bringer of a worldwide harvest, made possible by ingenious science, or a monstrous, hungry, and potent blight on the possibility of healthy and ethical agriculture.

I imagine the real Monsanto sits somewhere in between: a corporation trying to grow food for the whole world and grow itself in the process, blundering along like the rest of us, unable to fully account for all the effects—social, medical, ecological—of its innovations once they leave the lab, under economic pressure to not stare its dark underbelly directly in the face, and convinced, perhaps rightly, that the nutrients it provides on an unprecedented scale to the people who urgently need them more than make up for any ethical quandaries. Nobody likes talking about controversy on an empty stomach.

We, the Art Farmers, are the anti-Monsanto. We are here to raise a crop of art which will grow so tall and fast it can skewer a cloud by July, while the corn is only waist-high. We are the alien weeds in the fields. We are monstrous stalks of horsetail, growing more and more resistant to monoculture every day. And we will flow into you, if you give us the chance.

There’s this weird cliché that artists, by definition, are psychological crack-ups, masochists of the highest order. “I’m just not talented enough,” I whined at one point on the farm. All of my college friends were off making money and saving the world while I stared at my navel in the prairie. Writers my age suddenly had work in all kinds of major publications. I was feeling deeply unprepared for The Real World. “You picked this,” Lindsay said. “Being an artist means constantly flipping between total egotism and absolute soul-crushing self doubt,” she said. Of course, Western culture prefers to call this borderline disorder or bipolar disorder and make it go away. Let’s fix that chemical imbalance.

The choice to make things often involves rejecting these narratives—the productivity Kool-Aid that keeps Monsanto plugging away—and diving headfirst into the crazy. One’s prerogative as a creative is to dip across every line and then come back to the safe side, but I’m scared of one day not being able to get back across. I don’t know which causes which—whether making art allows you to reject these narratives or rejecting the narratives leads you to make art, but the two almost always go hand in hand. Something about near-psychosis allows you to question the clichés and purported realities of societal life enough to give your work a strong jaw and sharp teeth. I like to think that the madness and discontent is not just destructive but productive, compelling you to produce out of emotional necessity, out of a need for the feelings and chaos and confusion to drip out of your head and into the world. Of course you run the risk of fetishizing a mental condition that makes you deeply unhappy. And of course, you run the risk of diving too deep.

On my first day of work, we drive Ted’s pick-up to another anonymous Nebraska town, stopping in front of a rundown old house. A man arrives in a silver van, gives Ted an enthusiastic hug, and unlocks the place. We carry all of the furniture— dressers, desks, a bike, an easel, sports equipment—out into the yard and then hoist it into the

truck. The man hires a couple of us to help him clean out the place for a few hours. “Who said they needed a dresser?” Ted asks in the car.

Days are hot and dry and sticky with our sweat, or torrential. When it storms, you can see the twisters forming in the sky. The rain beats down on Victoria’s tin roof and, despite the leaks, the unfinished house somehow feels safe. By morning the farm is a great swamp and we hop across trails of pallets and hydroplane down the muddy roads.

The town is twenty minutes away by car: twelve silos, a post office, a water tower, a bank, and a bar called the Don’t Care Bar. Understaffed, they hire Lindsay, who has waited tables before and gets measly tips from the local wannabe biker gangs.We sit in the corner booth during her shifts and try to slip dollar bills into the back pockets of her jeans and get hit on by the locals.

“Whatever happened to old Ted? Is he still running that hippie cult?” a gruff man in overalls asks his friend.

“He’s gotta be seventy by now. I don’t think he’s got any kind of a plan for retirement, now that his wife is gone.”

“Wife? Another? Where does he find them?”

The four-dollar gin and tonics become beers become a cider for the road, half off because it’s to go. We drive home with the radio on, the fields sparkling with dense hordes of fireflies. The roads are straight and fast. You can do ninety and not get pulled over unless you have plates from a blue state. On my third day on the farm I stumble into the barn, which is actually four barns salvaged from all over the state and stitched together. In the midday heat the inside is pitch black, but I can feel its size even in the dark. I fumble for the light and poke myself on a nail – the walls are raw wood. When I find the switch, I see the heaps of stuff: paper, construction supplies, old wood. The ceiling is high and seems to go on forever. An infinite warehouse. Narrow walking trails edge through the chaos as if they were hiking paths. The quantity of miscellanea is so massive that it’s hard to pick up any one thing. A hacksaw balances on a canvas stretcher, leaning precariously against a doorframe. Piles of Folger’s jars from the past fifty years are filled with nails and drill bits. At one point, the floor drops off, revealing a carpet of dirt about five feet down. (“We’re working on it,” says Ted.) Cans of congealed paint and rusted out bits of cars and unidentifiable fluff have grown together into uselessness. A brightly decorated bandsaw hangs out in the middle of the floor. An enormous Hy-Vee sign hangs from the ceiling, dusty neon watching over us all.

Things accumulate here, piling up in the barn until it becomes a cavern of thing that once seemed useful but now just take up space. They’re like comfort objects, there in case you need them, though you couldn’t find them if you did and likely won’t remember they exist. “Let’s just say it,” Aimee says, “Ed is a hoarder.” The term, while accurate, feels derogatory, like we’ve relegated a man we all respect to a category of people including those whose dignities have been sold by their families to reality television. Or it feels pathologizing, as if we have accused him of having a personality disorder. All of my capitalist sensibilities are telling me this guy is a wacko and the whole farm a little shady. I put a lot of energy into suppressing that particular judgment.

It’s not all bad. Character accumulates here, too. It hangs in the air, in the murals and graffiti and the meadow where sculptures grow like trees.Thirty years of artists have loved this place. You show up, and you can feel it in the bones of the buildings—affection has soaked into the ground and found its way into the limey water and makes the mulberries so sweet and the grass so vigorous. It tells us to be reverent. It’s message is twofold: This is your place to love and do what you will with as many have before you, but you will leave, and your love will be piled onto the rest, your art will become another layer to be painted over.

The state of the barn feels more like a misguided attempt at practicality than a pathology. Everything in it is hypothetically useful, and, considering none of us can pay for board, if Ted needs any one of these things, having to buy it isn’t practical or ideal. In the work of feminist theorist Lauren Berlant, hoarding is explained as the inevitable response to the unstable nature of the consumer. Capitalism promises satisfaction through consumption, but that satisfaction is never lasting. Hanging onto objects, to the rest stops that are supposedly the vehicles of this satisfaction, feels like a way to make that happiness permanent. But to hoard comes at the price of isolation, of choosing possession over being in circulation. “In circulation,” writes Berlant, “one becomes happy in an ordinary, often lovely, way, because the weight of being in the world is being distributed into space, time, noise, and other beings… In [the fantasy of hoarding] one is stuck with one’s singular sovereignty in an inexhaustible nonrelationality.”

***

I’m talking to a Finnish guy in a Lao hostel. It’s the winter of 2013. He’s wearing elephant-print pants with a hole in the crotch and enough bracelets to count as training weights. I am eighteen and have been miraculously liberated from my parents for long enough to backpack the Banana Pancake trail alone. I don’t know much about backpacker culture, but I’m quickly assimilating. I’ve learned the routine: hi-where-are-you-from-where-areyou-going-next-oh-I’ve-been-there-there’s-a-reallygreat-hostel-how-long-have-you-been-travelling.

Normal lives are taboo: For the backpacker, home is the tangled network of hostels and single-serving friends that stretches across most of the world like a chart of a phone carrier’s coverage or an airline’s seasonal magazine route map.

“I want to see the real Laos, you know?” he says. I do know. What he means: he wants a nice old lady to invite him back to her house where she’ll serve him authentic tea and introduce him to her shy and beautiful daughter and they’ll all laugh and smile and come to love each other even though they can only communicate through body language. He wants to chop off a piece of something secret and take it home and show it off.

I doubt the impulse to see the marvels of the world with your own eyes has the same power in an age flooded with images: You’ve already “seen” the Taj Mahal; you’ve already “seen” the Eiffel Tower. They say seeing them in person is different somehow, but I’m not sold.

Imagine a matrix-esque simulation where you can go anywhere in the world and have a full sensory experience of that place. I’m talking goggles, electrical nodes, that scary Matrix tube of wires that plugs into the back of your skull, whatever you need to believe it. You can run a five-mile loop around the gardens of the Taj Mahal if you’re so inclined, and even go inside. It’s all HD. We’ve programmed in the smell of the ginkgo trees, the chipping in the marble beneath the nice Quranic script, the way the fog hangs in the morning and then evaporates with the rising of the sun. Hell, we’ve programmed in fifty years of accurate weather predictions, adjusting for climate change. Do you still feel the need to go to Agra?

*I don’t just want to see it, you protest, I want to feel its presence, its aura, to stand in the same place as thousands of years of tourists who found it even more awesome than I will. *On some level, I believe in this nugget of reality, of authenticity—a badge of real-ness that can’t be imitated. But I can’t decide whether this claim to “real-ness” has merit.

When traveling, we like to think of the developing world as encased in some sort of resin that keeps it in stasis. We romanticize this cultural subsistence agriculture as an alternative to our monoculture of productivity. We want to go to these places and be voyeurs, to watch them from the panopticon of our Western-ness and come back with stories and artifacts that will give us a leg-up in the perpetual struggle for social and cultural capital. And yet by observing these places we are changing them; the influx of enough backpackers makes the whole culture gravitate around a tourist economy. You can’t have an authentic tea with that nice old lady, but you can share a beer with her son who has just moved to a town with more tourists than locals to open a tour bus business because it’s the only real way to make a decent profit around here. We are mutating cultures, “contaminating” them through our wish to experience them before they are so contaminated they become absolutely nowhere.

The reality is that backpacking creates a culture that isn’t tied to a specific location. It was born as a diaspora without a homeland, existing in the network of hostel common rooms and tourist bars where the customs are identical and the people are the same across continents. Through this culture of observation, you can go anywhere you want and never really feel out of place. This may not be a good thing.

I’m not sure why we still do it.

***

One role of mythology, writes Joseph Campbell, comparative mythologist extraordinaire, is to sanctify the land, to claim it. The term sacred, before it swelled to encompass its current meaning, is a derivation and amalgam of two Latin term: *sacerdos*, meaning a priest or priestess who guards a temple or sacred space, and *sanctum*, the space itself. The sacred hung in the relationship between human and space, space embodying the spiritual energy of some deity, the person watching the space, acting as spectator and container of that energy.

Plotinus describes the sacred space as designed to “capture” the deity, as if he or she is a flighty thing who may otherwise evaporate into the ether and never be seen again. The space needed to be an “appropriate receptacle.”

But if you catch her, will she stay? I imagine getting attached to a place somewhat literally: you wrap your thread around the person beside you, pulling it taut and making a double half hitch around your own waist and then you send it out again, to catch another and come back to you, as always. With each stitch your needle plunges through the air, the dirt, around a sapling, under a set of purple covers or through a crevice in the drywall, weaving the netting of your attachments into the fabric of the space. Soon you can’t walk anywhere without tripping over the threads.

These days the people are scattered. People I love are in San Francisco and London and Boston and Delhi and Greece, and my net of attachments spans the whole worldwide. The string knots around something here, something there, but largely places are forgotten entirely: To reach from here to India without getting stuck on the top of skyscrapers or tripping up airplanes, your strings have to be pretty high off the ground.

The word “temple” only dates back to ancient Rome, but its etymological roots had connotations of being literally “cut off” from the space around it, as if the ground was suddenly discontiguous.There had to be a line of sorts, a demarcation of where normal earth ended and the sacred began.

I spent countless hours this summer searching for the modern equivalents. They’re hard to find in a secularized world. I found them in galleries, white and stark like giant ice cubes, great museum complexes designed to eliminate all distractions from the pieces. The power of art, writes Marcuse, begins when “all links between the [art] object and the world of theoretical and practical reason are severed, or rather suspended”—cut off from hard-knocks materialistic, utilitarian reality like the temples of old. All that austerity makes galleries hard to love.

Art Farm is the alternative, I guess. It is a space made sacred by being cut off from circulation, like a hole punched out of Monsanto land, an incubator for a culture entirely separate from the surrounding sea of corn like a hostel in a Lao village.The farm has its own mythology, rich with the legends of heroes, demons (i.e. the possibly rabid raccoon we live with), and personal familiars. Ted tells the story of an artist from a couple years back who sliced his thigh open while clearing part of the prairie grass with a machete. He insisted on sewing himself up on the porch of the farmhouse with embroidery thread and a bottle of whiskey. And then there’s the resident who, en route to the farm, got slammed with a traffic violation so extensive that he had to complete extensive hours of community service before he could leave the state. Every year, somebody gets arrested.

We make our contribution. On my first day of work we plant trees. The holes are already in the earth, which is brittle from the direct prairie sunlight. It will become softer now in their shade. I keep each sapling straight as Z sprinkles dirt around its little roots. I hold it delicately between my index finger and my thumb and she pours in water and packs the mud down with bare palms.The ground around the tree gets denser and denser but I can’t imagine the baby cedar will manage to stay rooted through the June tornadoes. The prairie plains don’t get along with trees so well.The sun makes our hair hot to the touch and dirt cakes around our ankles. Decades will have to pass before incoming artists will have shade. I will be at least forty by then. The tree doesn’t care; he won’t hurry for me.

“I feel like we’ve given birth to a child,” says Z, dusting off her hands.

“It needs a name,” Raluca says. We look at it.

That night it storms. The wind slams shutters and Ted ushers us onto the prairie to watch the cyclones form in the sky. Hot and cool air, fluttering this way and that. In the morning the tree, hardly a twig, is still there. Larger ones, planted by residents decades back, have lost limbs. We call him Saint Cyclone, because he made it. He had worked his first miracle. We sanctified him as the permeating spirit of the place, dumping him onto the heaping pile of Farm lore.

I think in order to make riveting work these days, you have to worship your own gods. Campbell applied his theories of ancient shamanistic mythologies to explain the role of the 20th century artist. “The shaman is the person, male or female, who in his late childhood or early youth has an overwhelming psychological experience that turns him totally inward,” he tells Bill Moyers on PBS. “It’s a kind of schizophrenic crack-up. The whole unconscious opens up, and the shaman falls into it. This shaman experience has been described many, many times.” Spiritual authority, the power to interpret, fell on the shoulders of a single initiate, who drew wisdom and magic from personal familiars that spoke to him and him alone.

When ancient societies made the shift from hunting and gathering to agriculture, cultures rejected the old shamanistic way of life. This made sense with the hunter lifestyle, which prized and depended upon individual prowess, but in a planting society success was dependent on external factors, like rain, but also on the hard work of every member of the group, with no place for virtuosos. Myths had to have the ability to bind families and villages together in a cohesive unit for shared survival. Spiritual life fell to the people, who shared a pantheon of communal gods, often masked and distant, never appearing to the individual. Planting is about the link between life and death, the way the seed falls to the ground and grows the food that keeps the people alive and then dies, leaving seeds which will grow again. Campbell retells a planting-culture myth that encapsulates this shift, in which the individualistic shamans, in their arrogance, piss off the sun and the moon, which desert mankind, leaving the world dark and barren:

The shamans say, oh, they can get the sun

back, and they swallow trees and bring the

trees out through their bellies, and they bury

themselves in the ground with only their eyes

sticking out… But the tricks don’t work. The

sun doesn’t come back. Then the priests say,

well now, let the people try… [The people]

stand in a circle, and they dance and they

dance, and it is the dance of the people that

brings forth the hill that grows then into a

mountain and becomes the elevated center of

the world.

The dance of the people brings back the sun.The shamans are “lined up, fitted into uniform, [and] given a place in the liturgical structure of a larger whole.” Once assimilated into the rules of a society that has no room for magic, the shamans are faced with a choice: liturgy or interiority.

***

At seventy-two Noah Purifoy left for the California wasteland to build his world. In 1989 the desert was still arid and empty, teeming with potential for solipsism. Joshua Tree would have been a blank spot on AT&T’s coverage map, a gap in the spreading virus of constant connectivity that nobody bothered to fill or think much about. It was a mythical barren wild where art couldn’t be contained in white cubes and preserved for posterity.

The critics call this his Environment. The capital-E denotes that the term encompasses all of the sprawling little-e “environments” included within. Each environment is wonky assemblage, so-called junk dada composed of desert trash. If Purifoy’s work is any reflection of local demographics at the time, your average resident was a toilet married to a bowling ball. Driving your truck fifty miles from civilization to dump is almost universally cheaper than paying for waste disposal. A friend of a friend of a friend once found a mountain of ties twenty feet tall out there. Under mass-consumerism, everything is buried alive. The afterlife, for all manner of unwanted miscellany, is located in the extreme conditions of Joshua Tree.

Purifoy’s isolation sustained him through the turn of the century until his death in 2004. He died surrounded by the artifacts of his internal landscape, made material through his hard physical labor. In the years since the extreme climate has gnawed away at the structural integrity of the environments: pieces which once supported human weight have grown too dangerous; dust, wind, and heat have worn away details. He wanted it this way. His artistic remains are, like him, becoming the desert.

I had a friend who told me not to be a writer unless putting words to the page felt like shitting. Don’t follow it, he said with a little too much gravitas, unless it has to come out, one way or the other. As Purifoy aged, his work ethic became frenetic, colored with the increasing urgency of the ultimate deadline. Nine years before he died, he shared lunch with an interviewer in his mobile home. “It’s been said that if you don’t accept death as an equal part of existence you’re in for trouble somewhere down the line,” he said. “I’d never given much thought to any of this because I thought I’d live forever, but I’ve come to realize that’s not the case. That may have something to do with why I push myself so hard now to finally get the work out that’s always been in me.” His hardy body: a little metabolite, a machine for the translating the blueprint of his mental space into the physical sphere, pulling image and idea out of his head and into the physical world to save it from the decay of his flesh.

Isn’t this what we’re all doing when we create? We slide our hands, wrists, and forearms down our throats and back up through our nasal cavities to cup the base of our brains, unraveling the tangle of electric pink matter. We pull it out, in one long strand, through our mouths and proffer it. Look at this, we say. Somewhere in that string of you is a whole solar system. I think of the way scholars refer to Kafka’s “universe,” as if each work of fiction was a different episode forming a singular plotline, the genealogy of another reality discrete from our own, as if writing was a wormhole, sharing the particular timbre and hue of the artist’s interiority with the rest of us. I imagine Noah Purifoy’s ghost wandering the environments by night, haunting the labyrinths built to contain it.

For the contemporary artist-shaman, the price of the magic of creation is pretty steep. Insanity, Foucault explains, is a societally constructed malady. We made up the line between sane and insane. Reality within civilization isn’t necessarily some hard and fast objective truth about the world, but simply the code of conduct and set of beliefs to which we all subscribe. A loss of connection to reality isn’t a loss of connection to the world, but to other humans. It’s a loss of the common language of culture that binds us all together—the rules of your world are not the rules of everyone else’s anymore. The ultimate goal of art, I suppose, is to chart the unfamiliar territory beyond the scope of that language, to translate the untranslatable into something that can be digested and shared. I’m not sure if this is possible. When I think about Noah Purifoy I think about someone who sacrificed community and the possibility of happiness among other people for work that deeply fulfilled him. Maybe he gets all that missed connection posthumously, when disciples trek out to Joshua Tree for communion with his work. Me, I’d like to feel that before I die.

***

Art Farm is a cult: it’s isolated, it’s insular and out of circulation, but it’s a living culture like anything else. We just operate in a different kind of currency. We don’t talk in pounds and pesticides and profits, but in citronella candles and brushstrokes and hickeys. It’s not stabilized against the dollar, and its so-called value fluctuates wildly.

Another of my favorite myths that Joseph Campbell tells to Bill Moyers on that PBS program is the story of the young boy who has a vision in which he realizes “the central mountain is everywhere.” Campbell explains:

The center [of the world], Bill, is right where

you’re sitting. And the other one is right

where I’m sitting… What you have here is

what might be translated into raw individual-

ism, you see, if you didn’t realize that the cen-

ter was also right there facing you in the other

person. You are the central mountain, and the

central mountain is everywhere.

The middle of the world is at the heart of a Nebraska barn piled with thirty years of accumulated debris. The middle of the world is in every ear of glyphosate-proof corn that has ever graced the Earth, in every Monsanto executive, in the amputated tip of Ted’s missing finger. It is here, with you, as you read this, and it is here with me as I write this however many weeks prior. It’s not going anywhere.

Winter 2015 - Possession

I

Last October, I had this crazy stress dream. In it I’m face to face with Maya Deren, the author of a book I’m reading on Haiti. She’s gorgeous, which makes me nervous. “But you’re dead,” I say. It’s true: After only 44 short years her brain had hemorrhaged, in defiance of a new, improperly-prescribed medication. It was 1961, the same year my mother took her first steps.

I put a hand on her shoulder. Her bare skin is hot beneath the pads of my fingers, almost malleable, and I worry I will damage it, leaving sticky prints on her back. She might have been a sculpture in the works: still raw, still clay. I plunge my hand through her sternum, parting her ribs and holding the hot organs in my palm.