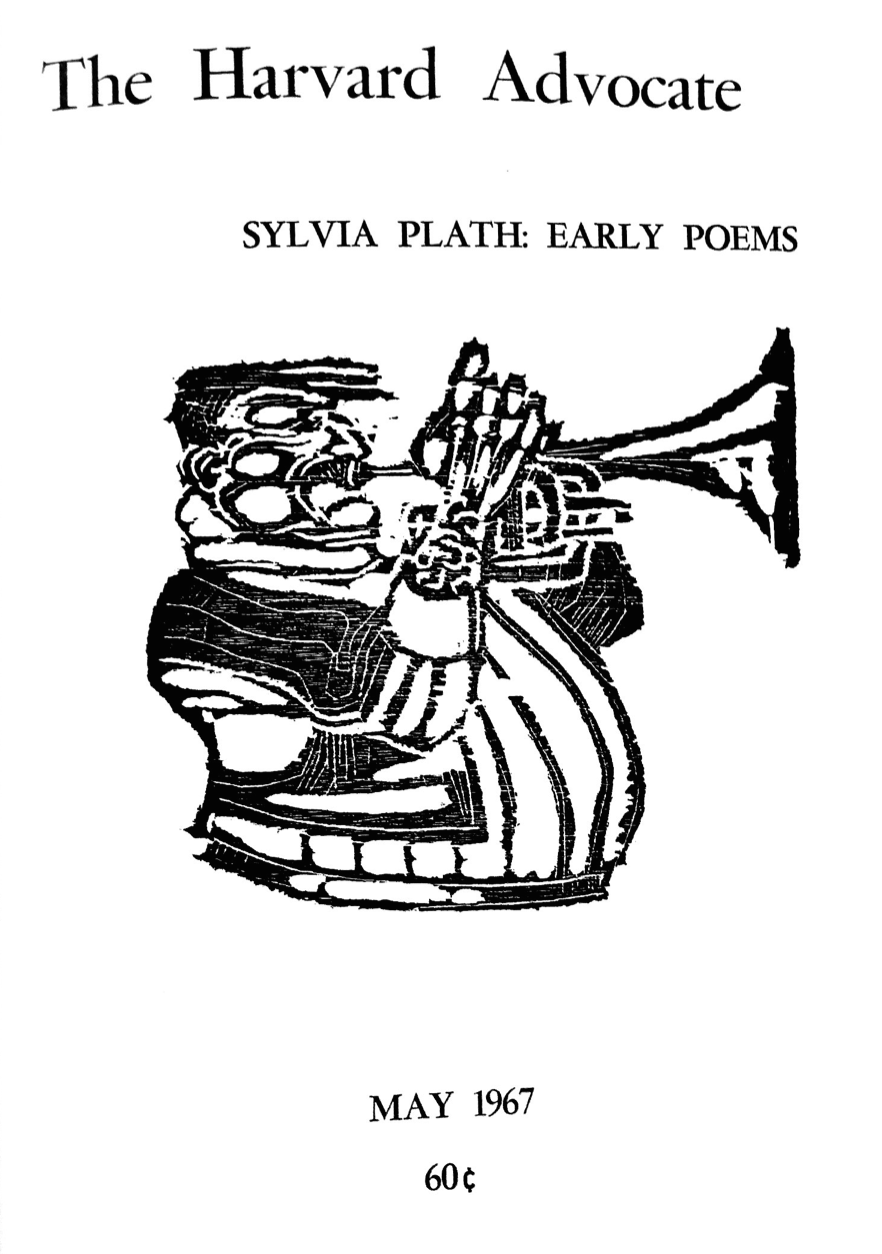

Winter 2016 - Danger Issue - The Harvard Advocate

Archived Notes • Winter 2016 - Danger

REPRINTED FROM 1921 ISSUE

It is an ungenerous platitude and a true one, to say that by far the greater part both of our actions and our thoughts have for their roots noting but dogma and cant. It is as true of politics as it is of religion; and it is becoming daily truer of the hitherto untrammeled field of criticism. In politics we have had our Robespierres, and we are still suffering from the effects; the political market is glutted with *liberté, egalité, fraternité*. Mr. Wilson has succeeded Jean-Jacques, and Lenin is still with us. In religion Bossuet has followed has followed hard on the heels of Luther, only to be displaced by the sing-songs of “independent morality” and the emasculated doctrines of modern Sunday schools. But literature, all through the ages, has made a strong stand and fought a brave fight against the Scylla and Charybdis of cant and dogma.

It was not till, weakened and unmanned by the terrible inroads of Taine and Brunetiére that our modern criticism succumbed to the temptation to make of literature an exact science. Not until the shade of Sainte-Beuve had been laid to rest, that the French mania for classification took firm hold upon us. Today we could no more “appreciate” Shakespeare without applying certain scientific laws to the progression of his genius, without dividing him into as many compartments as there are stages in literature, without splitting him up into a “before and after,” than we could thoroughly enjoy the movies without music. It is as much an essential of our literary self-consciousness as fur coats are of our social standing. We could no more attribute the proper “literary emphasis” to Charles Lamb or William Hazlitt without first knowing what prenatal influences shaped their minds, without placing them in the wake or the beginning of a classic or romantic movement, than our literary consciences would allow us to split infinitives. Even in our moments of larger recklessness we cannot altogether forgive a dramatist’s transgression of the “law of time and place.” Voltaire is as unintelligible to us as Zeno if we do not know that “he marks the transition from the sixteenth to the seventeenth century”; French classicism would be a hopeless riddle to us if M. Lanson did not tell us that it is a “combination of rationalism and aesthetic taste.”

In short, literature would be a complete waste of time if we could not seat ourselves before it as we would before a vivisection table, dissecting here a phrase or a general movement, scrutinizing there a “tendency” or the fulfillment of an immutable law. In our mad rush to classify, to make literature “accessible to every home,” personality and style go by the board. Whatever cannot be made to fill a text-book on the “Origin and Development of the Novel” or the “Evolution of the Drama,” whatever, in sort, is real literature we cheerfully ignore. It has no vendible character; it cannot be spouted in a classroom—it has not even value as erudition. All that can be expected are a few workable rules, a few “literary tests” which can be indiscriminately applied and unswervingly followed. This is criticism; this takes the place of appreciation.

Archived Notes • Winter 2016 - Danger

Some facts about risk:

* Recklessness is not a consistent trait. According to Elke U. Weber—the man who is to risk what Pavlov was to obedience—there are five domains of risk-taking, and our propensity to take risks differs across these domains. In other words, being an inveterate gambler makes you no likelier than the next person to enjoy skydiving, or to take back a cheating significant other.

* The amount of risk we feel comfortable with is fixed, and we will modify our behavior to make up for changes in risk-level. The paradigmatic case is the driver who buys better brakes: He’s no less likely to end up in an accident because, to compensate for the lessened risk of his brakes failing, he’ll tend to drive faster.

* People in committed relationships are less likely to take risks because the pressure is off to woo potential mates with flashy gestures.

* Driving is objectively risky. It is one of the riskiest things we do on a regular basis. It accounts for about 30,000 deaths per year, in the United States, and is the leading cause of death for Americans aged five to 34. It is perfectly reasonable to fear that we will die in a car crash. Over the course of a lifetime, one in 108 Americans does.

But we don’t fear it. Vehophobia is rare—much rarer than aviophobia, even arachnophobia. It is so generally un-feared that articles about risk will cite it as the foil to activities that tend to inspire anxiety: You are much more likely to die in a car accident than in a plane crash, of a rare disease, of a shark attack, etc.

The reason we don’t fear driving is a product of evolution. Generally speaking, we are programmed to fear what early man feared: that which we can’t control, that which seems to pose an immediate threat to our safety (Picture a highly agential tiger coming right at you.) A correlative to this is that fear strengthens memory. So, when a fear-inducing event is covered in the media, our brains latch onto it, and perceive it as being likelier to befall us than it is.

Driving fills none of these criteria. The danger at a given moment seems small. Car crashes receive little news coverage. There were no cars in the veld. In fact, the instincts that make us fear what early man feared incline us to act foolishly in the face of vehicular peril: When something is speeding toward you, your brain—sensing an animal predator—tells you, freeze.

In Kolkata, where I spent this past January, you are roughly 1.6 times as likely to die in a traffic accident as you are in America. My rock and a hard place were a bus and a concrete road divider, usually inhabited from the backseat of a three-wheeled, open frame auto-rickshaw. The backs of the autos said, “Obey The Traffic Laws.” The backs of the buses said “Danger!” But even though I was more attuned to the perils of driving than I normally am, I couldn’t truly fear it.

At first this was frustrating. Not because I wanted to fear a thing I couldn’t avoid—Kolkata is emphatically non-walkable—but because I have a tendency to fear things that, statistically speaking, I shouldn’t. The preceding weeks had offered striking proof of it. Spending the holidays in Harrison, New York, I realized I’d developed a fear of movie theaters shootings: a receptacle for a broader anxiety about mass shootings that I worry might eventually make me fear all public spaces.

In terms of its status as a potential danger, mass shootings are the opposite of driving: low risk, high fear. Going into a public space will never be “risky.” In order for an incident to qualify as a mass shooting (acc. the US government), three or more victims must die in an “indiscriminate public rampage.” Six shootings from the past year fit the bill—not a small figure by any means, but many fewer than The Washington Post’s “more one mass shooting per day” headlines suggests. In 2015 in the US, 367 people died in mass public shootings, slightly fewer than the number who died falling out of bed.

But unlike driving, a shooting pushes all of our evolutionarily-programmed fear buttons. It is immediate, literally as fast as a speeding bullet. It is intentional: another person deliberately trying to hurt us. It is outside of our control and has what Don DeLillo in 1993 called an element of “shattering randomness.” And when it happens, it’s news. It rides that fear train straight to the hippocampus, and sticks.

The upshot of all this is that fear and risk, complementary though they might seen, in fact have nothing to do with each other.

There is a positive side to this: For every non-risky thing we do fear, there’s a risky thing we conveniently don’t. In Kolkata, it was heartening, even thrilling, to be greeted daily by my inability to fear a risky thing—to know precisely how much danger I was in, to know it to be a higher risk threshold than I am used to, and yet not feel fear.

Unfortunately, prescriptions for dealing with the other side of this neurological coin often fail to account for the discord between fear and reason. A typical method for tackling a so-called irrational fear is to appeal to reason—to tally the hard facts amassed in our corner and tell ourselves that the feared occurrence is extremely unlikely to occur. In other words, to evaluate the risk. Not the way our brains do make when faced with a hungry tiger, but consciously, a fact-based calculation that yields an objective, non-instinctual assessment.

But treating fear like risk is an ineffective means of assuaging it. Because we haven’t falsely assessed a risk. We don’t believe that the feared event is more likely to occur than it is. We’re just scared—the victim of our brains reacting in ways that made sense, back when the latest technology was fire.

This method of fear-management—providing ourselves with information that belies a faulty assessment of risk—might actually make matters worse. If you consider yourself a rational person, reassuring facts can act on the brain like a placebo pill: I expect myself to respond positively to this kind of data; so, when facts fail to ameliorate my fear, I feel, at best, stupid, at worst, crazy.

It’s likely that several of my friends have experienced this too. But I don’t know, because we don’t talk about this kind of thing. Because while I can find articles in which Anne from Connecticut confesses to not being able to enter a movie theater without scrutinizing her fellow audience members for signs of derailed-ness; while I can form an imaginary alliance with the 35 percent of survey respondents who said there should be bag checks at movie theaters, I cannot confess this fear to a friend without fearing that they will be put off by it—will judge me the way I judge myself.

This view of “irrational” fear is insidious in the extreme. Because a crucial component of the misery that attends an “irrational” fear is shame: feeling like you’re wrong to fear the thing you do, because objectively, virtually risk free.

Admittedly, mere awareness of why we fear the things we do does little to stanch anxiety. But I believe that if we took the placebo pill out of the equation, if we stopped trying to quell our “irrational” fears on our own, we might stand a better chance of beating them. If we felt comfortable expressing these fears, with the expectation that our feelings will be validated and possibly shared, we might be able to escape the mental prison that an unvoiced fear can be. And then, perhaps, we could go see a movie together.

1. For more on the interesting politics of calculating shooting statistics, see Mark Follman’s coverage of the issue on Mother Jones.

2. According to the Gun Violence Archive, which uses the definition “four or more shot and/or killed in a single event, at the same general time and location, not including the shooter” to qualify events as mass public shootings.

3. <http://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/1887/the-art-of-fiction-no-135-don-delillo>

4. Specific relaxation techniques—e.g. breathing exercises, frequently prescribed by psychologists—can be an effective means of mitigating anxiety. But this is professional advice, not common sense.

5. <http://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/16/business/mass-shootings-add-anxiety-to-movie-theater-visits.html>

Archived Notes • Winter 2016 - Danger

The reputation of today’s college students has, by now, been raked through the mud in the pages of most of America’s prominent publications. We’re coddled, spoiled, out of touch, addled by an overdose of political correctness, desiring nothing other than to be swathed in comfort, shielded from anything our social-media fueled, reactionary hysteria might deem “unsafe.” Heralding the death of both free speech and American excellence, pundits and writers of op-eds have sounded the alarm on what they see as a veritable epidemic; the prognosis is dim.

For the generation raised in an era dominated by apocalyptic climate-change predictions and the post-9/11 discourse of terror, this may come as no surprise. All signs point to doom and destruction, and we are reminded tragically and frequently that danger is still unequally apportioned along age-old lines of identity and privilege. Can we be blamed for running to safety?

In 1866, The Harvard Advocate was founded to run in the opposite direction: For 150 years, Dulce est Periculum has been our magazine’smotto, rendering danger—not beauty or truth—the value by which we orient our writing and art. As President and Publisher, we have found that our organization lies in a disjointed cultural position: far from aligned with the op-ed pundits, but sensitive to their appraisal; a step out-of-sync with undergraduates and administrative deans who discount the real merits of danger. It’s an uncomfortable spot.

And it has lead us to believe that these warring factions have conflated two forms of safety. On the one hand there is physical harm, slander, discrimination, perils that tasted sweet to the wrong people in the past and must never do so again. On the other there is intellectual insecurity and combative debate, the grit of a challenge. To banish the second in name of the first robs undergraduates of the risks we need to both better ourselves and tackle more ambitious, collective pursuits.

The millennial generation has long been derided for ignoring such challenges. Before the reign of the “coddled” epithet, we were “apathetic.” To prioritize the perfect selfie angle over issues of global importance signaled our narcissism, we were told. But as we have turned our attention from Instagram feeds to more pressing social movements—Black Lives Matter, Occupy and its offshoots, the newly prominent campaign against campus sexual assault—a different source for our apathy has surfaced: fear. Cautioned and discouraged by the inability of our predecessors to adequately and definitively succeed, we worry about stepping on each other’s toes, panic at the thought of leaving someone out. When so many things are problematized, the scope of our ambitions narrows, and we begin to focus on small, immediate, and—in the grander scheme—relatively trivial concerns.

And nowhere does triviality seem so trivial as at our crimson-colored bastion of American academic elitism. Harvard, as understood by administrative envoys and Crimson editorials, applies too much pressure with its comps and cut-throat classes, generating an exclusive, hierarchical, and unsafe environment. This is sound reasoning, but reasoning that has come to inflate the relative smallness of collegiate pressure—and to ignore its many merits. As any top-rate athlete knows, if we want to improve, we must work hard, usually very hard. A small group of admission officers did not grant those who matriculate a carte blanche of permanent validation, and sometimes, we will deserve a C. Sometimes we will not want to hear a Marxist professor invalidate our future professions. Sometimes we will be cut. Insecurity in these moments, in a classroom or comp, can be a productive sort of discomfort.

But something about the Harvard bubble has obscured this logic, letting us equate personal invalidation with structural injustice and, most insidiously, ignore actual injustice. True, there remains on this campus a cornucopia of traditions and organizations tinged with distasteful remnants of archaic power structures, and there is much to be reformed within Harvard if it is to uphold its promises. Progress starts small, and it starts at home. But something is wrong when every student opines on exclusivity in Harvard’s elite social clubs, while remaining silent on issues far more central to our global future. We argue more about the politics of an introductory comp meeting than about actual politics. These conflations, these slidings of scale, arise from the same fear: a fear of offending each other, of potentially disagreeing, of confrontation. When we hold back, we stop talking, we stop listening, and we stop connecting. Very often, we stop acting.

Over the past four years, the two of us have seen a rise of that paralysis at 21 South Street: a tendency to swap sweet danger for bland cordiality, to keep meetings serene lest one undergraduate provoke another. Too often, the Advocate’s members say no to perils before tasting their flavor, closing their ears to each other and falling prey to suspicions that fracture meetings before they have begun. This fear of real engagement is particularly disquieting when it bears on relations to the broader Harvard community. Amidst the best intentions for organizational improvement, the Advocate find itself caught up in obsessive analysis of its own culture—in examining a minute position on this campus and trying to divine the mental states of all who perceive it. A quote spoken at the wrong moment, a candle misplaced—these are the details that have become invested with the greatest weight. Constant inward-facing dialogue has inflated our membership’s sense of self-importance beyond reasonable proportion. Hyper-concerned with imagined complaints, many become deaf to valid criticism and distanced from the magazine’s actual purpose.

As we bid farewell to the Advocate, we hope those left behind will recall that purpose’s primacy: This magazine should serve as a space for fearless debate over literature and art, our aesthetic risks ideally playing a small part in a campus culture that boldly demands not just extracurricular and dormitory justice, but racial, gender, sexual, environmental, and economic justice. The fear that narrows our focus to trivialities and personal affronts should impede neither pursuit, so we must remain vigilant to differentiate between species of fears, and of safeties.

To fuel that vigil, we return to our timeless motto, and to the firm belief that beyond its appeal as a decent spot for a cocktail, the Advocate still holds a commitment to one or two lofty ideals. On its sesquicentennial, this magazine—be it a victim of Comstockery, an organ of responsible criticism, or great organic zilch—has something to teach us muck-raked millennials: Danger, when shaken right, is still sweet.

Archived Notes • Winter 2016 - Danger

Among the theories that abound as to the authorship of Elena Ferrante is the suggestion that she is, in fact, a collective of writers. As with all matters surrounding the continually posed question of why she remains anonymous, Ferrante has an arsenal of analogies for such occasions. But we accept that Elsa Morante wrote both *House of Liars* and *Aracoeli*, she observed in the *Corriere della Sera*; Joyce, *Dubliners*, *Ulysses* and *Finnegans Wake*, in the *Paris Review*. We happily interpolate a career’s coherence where we are given someone to pin it to; in its absence, we flounder. Mercifully, the best recent criticism has been more attentive in conceiving of a kinship between Ferrante’s works that shouldn’t be difficult to see. In fact, Ferrante intimated a kind of unifying vision behind her early works over a decade ago in “La frantumaglia,” the last chapter in her non-fiction book of the same name (forthcoming in English this year). Reading those words now, with the Neapolitan quadrilogy behind us, offers another way to conceive of Ferrante’s evolution over time—lends it the appearance, even, of inevitability.

In 2003, Giuliana Olivero and Camilla Valletti of *Indice* wrote to Ferrante. They observed that her protagonists till then—Delia of *Troubling Love* and Olga of *The Days of Abandonment*—seemed to come from myths and models of Mediterranean femininity from which they had extricated themselves only in part. Was their suffering, the editors asked, “the result of this intermittent rapport with their origins, of this difficult and never resolved estrangement from traditional roles?”[1] Ferrante responded that she found their theory intriguing, but that to engage with it she couldn’t proceed from their vocabulary: “*origin* is too loaded a word; and the adjectives you use (*archaic*, *Mediterranean*) have an echo that confuses me.”[2] She proposed instead a word of Neapolitan dialect, inherited from her mother: *frantumaglia*. Though not standard Italian, it seems to follow a recognizable rule: *frantumi* means fragments or shards; the *-**aglia* suffix turns feminine plural nouns into pejoratives.

Because Ferrante suggests that she never asked her mother what was meant by the word, her initial sketches of what *frantumaglia* is work backwards, drawing inferences from childhood memory: “At times it made her dizzy, gave her a taste of iron in the mouth… it was at the origin of all suffering not attributable to a single obvious reason… it woke her in the middle of the night… suggested to her indecipherable tunes to sing under her breath that soon extinguished themselves with a sigh."[3] (Though Ferrante never states it, *frantumaglia* is clearly a femininely-coded affliction.) However, as she acknowledges that nowadays the word has more to do with her own conception than her mother’s, her definitions become increasingly abstract, though often related to a fear of losing the capacity for self-expression. It is the painful realisation of life’s incoherence and to confront the ugly frailty of bodies. It is both what causes suffering and what those who suffer are destined to become; it is an “unstable landscape” that violently reveals itself as your “true and only interiority.”[4] Drawing on a discarded passage of *Troubling Love* where a young Delia hacks off her hair in filial revolt, Ferrante summarized the effect of *frantumaglia* as the small movement that causes a tectonic shift. That moment, she wrote, dissolves distinctions of linear time, schematic ideas of before/after, past/present or myth/reality; sinks us into the primordial depths of “our unicellular ancestors” and “mutterings… in the caves,” all while we suppose ourselves anchored to the computers at which we sit.[5] What lends coherence to Ferrante’s vertiginous piling-on of definitions is the convenient fact that it functions in the same way as the concept itself: the ordinary opens out—in a sudden and not completely explicable way—onto the cosmic.

To consider what *frantumaglia* offers that “archaic,” “myths of Mediterranean origin” and settling accounts with the past to become “women of today” do not is an interesting proposition. In fact, it makes sense of the leap between the compact early novels and the sprawling Neapolitan cycle. First, that the series returned directly to Naples and to girlhood, depicting the course of a life rather than adult women in exile. Archaic can simply mean very old, but it also implies an element of incongruity—an antique object out of place in a prevailing present. Olivero and Valletti suggested an “intermittent rapport” with one’s past and origins, a failure to conform to or properly dispose of “traditional roles” as the source of suffering. Their phrasing implied adult women removed in time and space from their origins, and the management of their relationships to this past as the problem. Yet Lila and Lenù suffer in girlhood not from the residue of an unreconciled past either personal or abstract-historical, but in response to their immediate surroundings: protracted episodes of malaise “not reducible to a single obvious reason.”

As if to underline the fact that *frantumaglia* belongs not solely, or even first, to the upwardly mobile, middle-class protagonists of Ferrante’s first novels, *My Brilliant Friend* also features an expanded cast of Neapolitan women. Figures who had heretofore been peripheral—appearing only to Delia, Olga and Leda as threatening visions of fates narrowly avoided—became full and important characters in their own right. The dead Amalia of *Troubling Love *is supplanted by Lenù and Lila’s living mothers, Immacolata and Nunzia; Melina Cappucio is the *poverella* of *The Days of Abandonment*, minus drowning. Beyond the strictures of motherhood or marriage, Maestra Oliviero crucially steers Lenù towards a high school education, and Manuela Solara presides over the neighborhood with the secrets aggregated in her ledger of debts. Dayna Tortorici argues in n+1 that one of Ferrante’s strengths is her ability to lucidly incarnate concepts of feminist theory like entrustment and the “symbolic mother,” her gift to literary women “books that speak to them in a language their mothers can understand.” What Tortorici observes of Ferrante’s novels in general is also true here: *Frantumaglia* is a word legible to the women who would most identify with the experience it describes. In declining the editors’ lexicon and supplying her own, Ferrante rejects what might be considered “obfuscating theoretical language,” however well-intentioned it may be. Lenù’s mother openly resents her daughter’s intellectual pretensions. These women would sooner identify as Neapolitan than Mediterranean; Lila, by choice, never leaves Naples in her life. *Frantumaglia* is a formulation they might embrace, even if “myths of Mediterranean origin” is not.

By supplanting abstract terms with a very specific one, Ferrante was paradoxically suggesting a broader scope to her concerns and signaling the extent of what David Kurnick called in *Public Books *her “grand novelistic ambition.” Ferrante concluded that her problem with the kind of theory suggested by Olivero and Valletti was its neatness. The past, in her view, is urgent; it is not something that can be superannuated, but only possibly redeemed. Delia’s achievement is not to put distance between herself and her mother but to realise that she had “been” Amalia. Olga overcomes her abandonment only by realising the constitutive role the *poverella* has played in her life and according it its proper place. Ferrante, defining *frantumaglia *and her theory of female suffering in an ever more expansive and associative way, begins with her mother sighing and weaves around it an atmosphere of intangible menace, explaining and interpreting until that first image is of a piece with the collapse of time and the contemporaneousness of all history. Even if Ferrante had not yet thought to write them, it gives some account, perhaps, of the scale of her Neapolitan novels-to-be, and their deft interweaving of the personal and the political.

[1] “Il dolore è il risultato di questo rapporto intermittente con le proprie origini, di questo faticoso e mai risoltato distacco dai ruoli tradizionali?”

[2] “origine è un vocabolo troppo affollato; e l’aggettivazione che usate (arcaico, mediterraneo) ha un’eco che mi confonde.”

[3] “A volte le dava capogiri, le causava un sapore di ferro in bocca... era all’origine di tutte le sofferenze non riconducibili a una sola evidentissima ragione… La frantumaglia… la svegliava in piena notte… le suggeriva qualche motivetto indecifrabile da cantare a mezza bocca che presto si estingueva in un sospiro.”

[4] “La frantumaglia è un paesaggio instabile… che si mostra all’io, brutalmente, come la sua vera e unica interiorità.”

[5] “Il dolore ci sprofonda tra le antenate unicellulari, tra i borbottii rissosi o terrorizzati dentro le caverne… pur tenendoci ancorate - mettiamo - al computer su cui stiamo scrivendo.”

Features • Winter 2016 - Danger

*The Advocate* was a major part of my experience at Harvard, and a generally enjoyable one. I was a mostly unpublished poet then (that's a somewhat complicated story which I won't go into here) and suddenly I was provided with a venue and could expect to see my poems in print not long after I wrote them. It all came about through Kenneth Koch, whom I met in the fall of 1947, my junior year. He and I exchanged our poems and found we liked each other's work very much. Kenneth proposed nominating me for the *Advocate* editorial staff. But there was a catch: sometime during WWII there had apparently been a homosexual scandal at the *Advocate*, and the university had closed it down at the behest of a trustee in Boston who provided a lot of their funding. When it reopened after the war there was an unwritten stipulation that no homosexuals need apply.

My sexuality was known on campus, and the editors told Kenneth it would be impossible to appoint me. Kenneth, who didn't know about my orientation and who was a bit naïve about such matters, got angry and said that if I was elected and turned out to be gay, he himself would resign. This strong-arm approach ultimately worked: I was elected to the board and soon discovered that several other of its members were gay too.

Having scaled that hurdle, I settled into the board's activities and enjoyed myself very much. One aspect that was particularly agreeable was soliciting Frank O'Hara for material. I had known about him and knew him by sight on the campus, but had never spoken with him, since he had a somewhat intimidating look. I found that this image was misleading, and that Frank was one of the most open and welcoming people I had ever met. Although it was only about six weeks before I graduated, I started seeing a great deal of him and he ultimately became a wonderful friend and colleague. He, Kenneth and I would, along with James Schuyler and Barbara Guest would someday emerge as the so-called New York School of poets. Also on the board were future soon-to-be famous poets like Donald Hall and Robert Bly. Adrienne Rich was at Radcliffe at the time. I think we published her poetry but I'm not entirely certain. Other poets who were sort of “passing through” were Robert Creeley, Richard Wilbur and Ruth Stone. For all of us, I think, the Advocate, then located on Bow Street on the second floor over a dry-cleaning establishment facing the *Lampoon* building, was an island in a storm.

Features • Winter 2016 - Danger

REPRINTED FROM DECEMBER 1986 ISSUE

My experience on *The Harvard Advocate* seems to me to be in some ways emblematic. And though I would like to think that we are living now in more enlightened times than those, the so-called liberated 1960s, I fear that there are many readers—mostly younger, mostly female—who may recognize something of their own histories in the following:

Early in my freshman year at Radcliffe, I attended an introductory meeting at the* Advocate*. A few days later, I got a call from an upperclassman I’d met at the meeting. On our first date, he informed me of his ambitions: First, he wanted to be a poet. Second, he wanted to be President of the* Advocate*. And third, he had wanted me ever since he saw my wan, follow-cheeked and rather gloomy photo in the Radcliffe freshman register. What I understand now is that this photo was the very image of a pre-Raphaelite poet’s mistress. Not only did he want to be a poet—he wanted a girlfriend who looked the part.

And so we began going out. As I remember, it took him somewhat longer to ask about my ambitions. By then, I had given up all thought of being ‘a writer,’ which is what I had wanted to be throughout high school. The slot had, so to speak, been taken. How could I be a writer if my boyfriend was a writer? I’d never even heard of most of the famous poets with whom he seemed to be on a first name basis. So I announced—and decided on the spot—that I wanted to be ‘an artist,’ that is, a visual artist, something for which I had absolutely no talent, my output until then being limited to dreadful, sentimental, badly drawn linocut-Christmas cards I sent to family and friends.

Sometime during that year, my boyfriend was in fact elected President of the *Advocate*. He promptly appointed me Art Editor. (My memory is vague on whether such an editorship existed before). I was delighted. Not only did I have an important boyfriend, I had an important job. I immediately began adorning the magazine with examples of my own beastly awful (I am not being modest about this) artwork, with the somewhat more accomplished doodlings of other.

Sadly, and for reasons irrelevant here, I was less delighted with my boyfriend. And sometime over the summer between freshman and sophomore year, I told him so. The next fall, I fell in love with someone else—an artist as it happened—and immediately appointed him to be my one-man art staff. My original boyfriend was understandably upset, but was hardly in a position to accuse anyone of nepotism.

Meanwhile I faced a new problem: How could I be an artist if my new boyfriend was an artist? Perhaps I should go back to being a writer—though this is not the story of how I eventually did. In any event it was all becoming very confusing. And editorial board meetings—with their constant potential for psychodrama—were beginning to be a strain. So sometime during that year, or the next, I stopped going, and began instead putting down the *Advocate* staff for being stuffy, retro literary types with nothing to do but debate which superannuated British poets to give readings. My friends and I, so I thought, had better uses for our time, and while some of these things—protesting the war in Vietnam and Harvard’s stockholding in South Africa, for example—still seem worthwhile, others—taking mind-altering drugs, listening to James Brown and the Rolling Stones—appear, in retrospect, pleasurable but less urgent.

Looking back, I am saddened by how reactive, how (in the psycho-parlance of those times) outer/ other-directed my decisions were. At the same time, I feel enormous compassion and sympathy for my younger self: her misplaced priorities, her confusions, her stupefying insecurities. Even so, I am a little embarrassed by what I realize now to have been my complete inability to distinguish between art, power, and sex—which isn’t to say that later life revealed these distinctions to be always reliably uncomplicated and clear-cut.

I thought about all this again when I learned that the President and Managing Editor of the *Advocate* are women, and I wondered how much has and hasn’t changed.

Features • Winter 2016 - Danger

Against the tyranny of time and politics, imagine us the way we sometimes didn’t dare to imagine ourselves: in our most private and secret moments, in the most extraordinarily ordinary instances of life, listening to music, falling in love, walking down the shady streets or reading Lolita in Tehran. And then imagine us again with all this confiscated, driven underground, taken away from us. - Azar Nafisi, Reading Lolita in Tehran

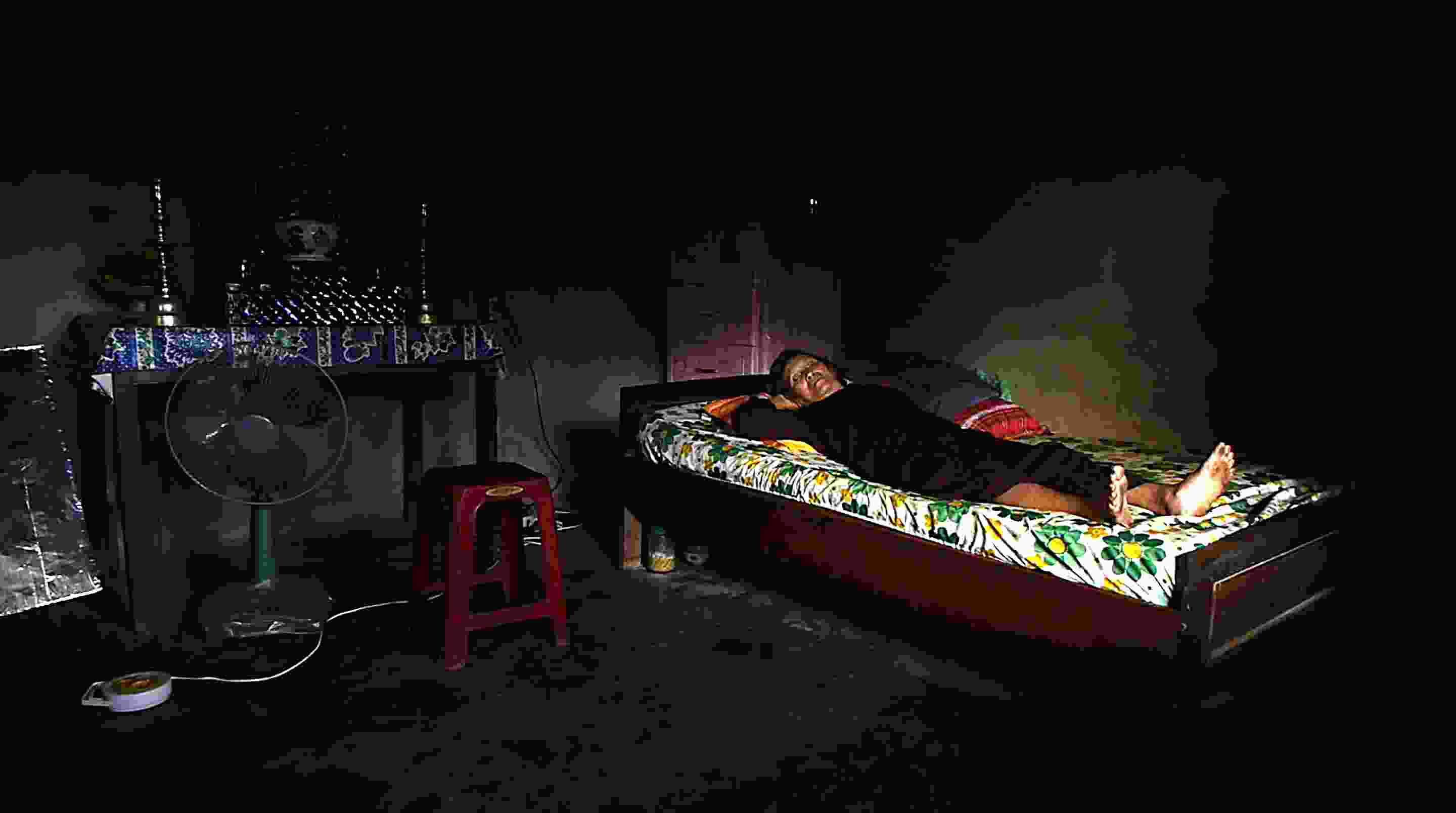

In closed societies, free speech and inquiry are dangerous. The cost of speaking out is shutting yourself in: drawing the curtains, turning down the lights, and speaking in whispers.

America isn’t one of those societies. It’s a place where the protection of speech—however unpopular—gets first mention in our Bill of Rights. By law, speaking your mind in America shouldn’t be a risky endeavor.

But Brown University student Christopher Robotham would beg to differ.

In 2014, Robotham felt compelled to start an underground, invitation-only student club where his fellow Ivy leaguers could discuss controversial opinions, or even play devil’s advocate to uncontroversial ones. Robotham said some students and administrators had become increasingly hostile toward truly open discourse on campus, with mere debate on topics like race construed as, in itself, racist. Some went so far as to label the discussions literal acts of violence.

Robotham’s group was, in other words, a “safe space” for free speech.

Around the same time, another Brown student, Katherine Byron, was working with other student volunteers to organize a different kind of safe space: one specifically designed to shield students from the purported dangers of that sort of free expression.

With a controversial debate on sexual assault set to occur on campus, Byron told The New York Times that she worried the event might “invalidate people’s experiences” and be “damaging,” so she organized a soothing room where students could retreat if the rhetoric of the debate proved too much. It would have pillows and blankets and Play-Doh. Even a video of frolicking puppies.

A student who used the room told the Times’ Judith Shulevitz why: “I was feeling bombarded by a lot of viewpoints that really go against my dearly and closely held beliefs.”

Safe Space Thinking

The phrase “safe space” was first used to describe gay bars of the 1960s as a physically safe and socially accepting environment for LGBTQ people. Recently, it has morphed into something more troubling: the creation of ever-larger spaces where anyone who is subjectively offended by anything can opt out of the conversation altogether.

The arguments for safe spaces use the same misguided justifications used by those who have advocated for censorship throughout the ages: That shielding ourselves from intolerant, dissenting, or merely confusing viewpoints protects us from those viewpoints and those who hold them.

That is precisely the argument University of Iowa administrators used in 2014 when they removed a piece of art by Turkish-born faculty artist Serhat Tanyolacar, who sought to facilitate campus discussion about race relations by creating a Ku Klux Klan robe out of newspaper clippings about racial violence. Instead of discussion, he got censorship, with university officials calling his piece “divisive, insensitive, and intolerant.” In short, the administration missed the point.

What’s different—and scarier—about safe spaces is not just that they can provide students with an easy-out echo chamber (complete with treats!), but that their advocates often accuse those who would insist on having difficult conversations of being violent aggressors.

One Tufts University student even told the Times’ Judith Shulevitz that her article criticizing Byron’s safe space at Brown amounted to “verbal violence.”

Conflating emotional safety and physical safety exponentially raises the stakes for those seeking to tackle controversial topics on campus through art, debate, or other means.

The examples of the power of the “safe space” mindset to shut down campus debate are numerous. Consider, for example, the case of Ashley Powell, a graduate student in fine arts at SUNY Buffalo. Last September, Powell—who is black—placed “White Only” and “Black Only” signs around campus. Students found them on water fountains, benches, and bathroom entrances, and were troubled to find these vestiges of pre-civil rights America seemingly alive on their campus.

According to a New York Times report, students opposed to the artwork seemed to conflate conceptions of emotional safety and physical safety, and did so to an extreme. One Twitter user wrote of Powell’s work, “Not only is [it] a hate crime, but it is also an act of terrorism.”

According to SUNY Buffalo’s independent student newspaper, The Spectrum, Powell addressed a large crowd at the school’s black student union in the aftermath of the controversy:

“I apologize for the extreme trauma, fear, and actual hurt and pain these signs brought about,” Powell said in the statement. “I apologize if you were hurt, but I do not apologize for what I did. Once again, this is my art practice. My work directly involves black trauma and non-white suffering. I do not believe that there can be social healing without first coming to terms with and expressing our own pain, rage, and trauma.”

Powell later told The Atlantic that the reaction students had to her piece was precisely the reaction she intended: “The signs are a reminder that just because you can’t see racism around you doesn’t mean it’s not there … I wanted people to feel something. I wanted people to realize they must confront racism and fight against it in their daily lives.”

While SUNY Buffalo did not completely censor the art, it demanded Powell place explanatory placards on the signs, diluting the emotional power she intended her message to convey and preventing the very revelation on which the artistic experience hinged.

This raises the question: Should campus artists be permitted to produce and display provocative and perhaps disturbing artwork like the piece at SUNY Buffalo, or must their work be made “safe” for college students’ consumption by dampening its emotional impact with a disclaimer? What about those on campus who welcomed Powell’s art and the conversation it produced? What did they lose? As Frederick Douglass reminded his audience in an 1860 speech, “To suppress free speech is a double wrong. It violates the rights of the hearer as well as those of the speaker.”

Sanitizing speech—through censorship, advisory warnings, or other means—never accomplishes its intended goals. In fact, it can backfire, creating martyrs for a cause and a larger platform for the controversial message.

Andres Serrano’s 1987 photograph “Piss Christ,” depicting a crucifix submerged in urine, would never have garnered the attention it did had critics—including those at universities—not called for its censorship. The same can be said of Powell’s art, which, after demands for its censorship, received media coverage across the country. This phenomenon has come to be known as the “Streisand Effect,” named for what happened in 2003 after singer and actress Barbra Streisand attempted to censor photographs of her Malibu, California, home and instead drew more attention to it.

Play-Doh Fortresses

What might ultimately be the greatest loss in sanitizing speech for public consumption is not a larger platform for those views, but the power that comes from understanding the world as it actually exists. Suppressing controversial speech does not actually do away with controversial viewpoints—it just hides them from view. If we censor speech, or hide from it, how would we know with whom we need to engage in dialogue? How would we even know when that dialogue is working?

Truth, of course, is what we should all be after.

Given this, the fact that the safe space movement is largely taking place on the modern university campus—a place that is meant to exist for the purpose of truth-seeking—is perhaps most troubling.

Higher education should provide an atmosphere where ideas are discussed, divisions created, biases tested, and offenses provoked. To be offended is to experience a necessary byproduct of a true education. If you attend college for four years and never listen to a contentious debate, see a piece of controversial art, or encounter an idea that provokes within you deep outrage, you should ask for your money back.

Offense is what we experience when we step outside of our echo chambers and encounter people who think differently than we do.

To shield ourselves from different viewpoints presumes that we have found ultimate truth. That we’ve reached the end of history.

But history is full of examples of people who falsely believed, as John Stuart Mill wrote, that “their certainty is the same thing as absolute certainty” and that no more debate or discussion is necessary. Even if a viewpoint seems objectively wrong, we still create a greater conception of truth through its confrontation with that error. Truth is like a muscle; it must be exercised to remain strong. That is how we maintain a living truth, rather than a dead dogma.

If we wall ourselves off from that process in the name of protecting our own beliefs and biases, we simply create a Play-Doh fortress with many enemies outside its illusory gates.

As for Christopher Robotham, the Brown student who started the underground free speech group, he thinks students shouldn’t try to avoid offense, but actively grapple with it.

“Intellectual discussion is worthwhile and, in its own right, enjoyable,” he said. “Open discussion and freedom of speech have tangible use in progressing society. I think that that has been forgotten is unfortunate.”

We live in an increasingly diverse society, where many people have remarkably different beliefs and outlooks on life. A “safe space” that shields us from that diversity offers us a place to forget—or willfully ignore—that fact.

Free speech in the name of seeking truth asks that, for the sake of humanity, we remember.

*Nico Perrino is FIRE’s Associate Director of Communications.*

*Alex Morey is Editor-in-Chief of FIRE’s award-winning news vertical, The Torch.*

Features • Winter 2016 - Danger

REPRINTED FROM DECEMBER 1893 ISSUE

The study of Feminology is, perhaps, the most interesting branch of scientific research. Now, although investigations in this science are made by most of us between the ages of eighteen and thirty-five, yet, in general, our attention is so absorbed by the concrete phenomena of single specimens, that a comprehensive knowledge of the subject is hardly ever gained.

My purpose, in this exposition, is to give the reader such an accurate general knowledge of this subject as an analytical observer like myself may well have. To accomplish my purpose, it is necessary to divide my work into three heads. First, to summarize the different classes of the genus *femina*; second, to describe a specimen of each class; third, to state those underlying characteristics which the whole genus possesses.

The genus *femina* is divided into two great families: *femina modesta* and *femina vulgaris*. In the latter family, the specimens haunt such loathsome dens, and exhibit such disgusting traits, that I cannot speak of them here. Suffice it to say that, since the unhappy creatures are generally the victims of circumstance, they are rather to be pitied than to be blamed.

The family *femina modesta* may be roughly divided into three species: first, *puella quieta*; second, *puella masculina*; third, *puella inconstans*. Though a few other species exist, they are so insignificant as to be unworthy the attention of the experienced feminologist. Such, for example, is the species vulgarly termed “pills.” These are so appalling in their dulness that one shrinks from observing a single specimen.

Let us return to the important species. The first of these, *puella quieta*, through her excessive shyness and reserve, affords an almost insurmountable obstacle to the investigations of the feminologist. However, if the feminologist have the good fortune to secure the regard and confidence of one of this species, his task of analytical observation becomes, comparatively speaking, easy.

In the winter, for instance, specimens of *puella quieta* habitually avoid observation. They are rarely to be found outside of their dwelling places; and even when so found, their timidity renders analysis impossible. In the summer, on the contrary, when, with the rest of their kind, they migrate either to the mountains or to the sea-coast, they become bolder. At such times they flit gaily about in herds; and it is then that the feminologist, if he be lucky enough to be on familiar footing with one or two specimens, may without trouble pursue his investigation.

The second species, *puella masculina*, is far more susceptible of scientific analysis. Indeed, since specimens rather seek than shun observation, the feminologist, in collecting data, finds no difficulty whatever. The specimens are abundant at all times and in all places: they roam on the public highway: they frequent public amusements: they are, in fact, a trifle too pertinacious in thrusting themselves upon the public gaze.

The principal characteristic of* puella masculina*—from which she receives her name—is her inordinate fondness for adopting the various forms of men’s dress. Indeed, the raiment which covers the upper part of her body is eminently masculine. In protecting the lower limbs, however, she has up to this time conformed to those rules which custom prescribes for the genus *femina modesta*: but, since she is of an impatiently aggressive nature, it is a question of anxious conjecture among feminologists, whether she may not in the future break through these laws of custom and adopt throughout the apparel of man.

Thirdly comes the species known as *puella inconstans*. This, of all three species, is perhaps the easiest to observe superficially and the most difficult to analyze thoroughly. At first easy of approach, *puella inconstans*, grows more and more elusive as the investigation continues,—till at last the feminologist, unless very ardent, is fain to give up in despair.

The species, puella inconstans, numbers among its specimens some of the most beautiful examples of the genus *femina modesta*. Although, as I said before, all these specimens seem at first easily accessible, yet each specimen is in itself so intricate that a thorough examination of it would be the work of a lifetime. The feminologist will find infinite difficulty in such investigations; because his most profound inductions and his most careful deductions are likely as not to be rendered valueless by a single act of a single specimen of this eminently capricious species.

I have briefly described each species of this interesting genus. Let me now state the principal characteristics of the genus as a whole. To do this I cannot do better than to quote the distinguished feminologist, Guy de Maupassant, whose remarks on this branch of the subject are practically final.

*“Je parle,” *he says, *“des femmes vraiment femmes, douées de cet esprit à triple fond qui semble, sur la surface, raisonnable et froide, mais dont les trois compartiments secrets sont remplis: l’un, d’inquietude feminine toujours agitée; l’autre, de ruse colore [sic] en bon foi, de cette ruse de dévots, sophistique et redoubtable; le dernier enfin, de canaillerie charmante, de tromperie exquise, de délicieuse perfidie, de tous ces perverses qualités qui poussent au suicide les amants imbécillement [sic] crédules mais ravissent les autres.”*

Features • Winter 2016 - Danger

I was out of shape when I showed up. I had kind of thought I was done. I had already made it through the hoop that counted, the admissions hoop. I had stuck my landing; now I could relax. They don’t tell you when they accept you that hoop-jumping is the official sport of the College. Especially at the beginning, I had this sense that I was in fact a hoop-jumping recruit, a scholarship kid. I had to keep jumping to earn my spot here. I would later talk about the sport in terms of the fix: that dopamine rush as your toes have cleared and you realize *you’re through*. In those first monthswe were all obsessed with recreating the experience of that first successful jump.

You get the sense that you have to join a cult to make it here. There are a lot of options for what cult to join, but you have to join *one* or you’re never gonna have a Real College Experience. Unless you have really great roommates. If you have really great roommates, you’re exempt.

To join a cult, you have to jump through that cult’s hoop. When you meet people here, you look at their bodies. You look at what muscles they have where, whether it looks like they could make a particular jump.

The cults recruit every semester. They run training programs that last most of the semester and culminate with the Jump where you either make it through the hoop and into the cult or you don’t. Sometimes there is a preliminary hoop that happens halfway through training, and if you don’t make it, you aren’t allowed to try to make it through the final hoop that semester. Every cult has its own hoop—different shapes, different heights—and each training program is tailored specifically to the cult’s hoop. Sometimes training for one can make it very hard for your muscles to learn to jump through a different one. Some hoops are easier for certain body types.

It’s a big deal. At the very end of College there’s always the prestigious Hoops prize which I think is for the senior who has jumped through the most hoops. If you get that you can do whatever you want. Then you definitely don’t have to jump through any more hoops.

I knew pretty early on which cult I wanted to try out for. I went to the Intro Training meeting. I was shaking a little bit when I walked into the culthouse—it felt important and intimidating, like the very wood was charged with gravitas. I looked at all the older affiliates and thought they looked much cooler than me. They were sitting around a heavy wooden table, with the Big Kahunas sitting in the middle looking important, looking out at us. All the jumpers were on the floor. All the affiliates spoke with the same cadence. Perhaps they spent so much time around each other that one had adopted another’s distinct manner of speaking in turn until everyone spoke with the same unified nuances. This was true of a lot of the cults: You could tell who was in what by how their voice sounded. All these affiliates made it through the hoop, I thought to myself. This terrified me. I imagined their bodies tensing up with nerves, sprinting and vaulting and *clearing the hoop*, muscles taut. I imagined the smiles on their faces when they stuck the landing. Some of their bodies had since gone to seed. Once you made it through the hoop, I guessed, you didn’t really have to stay in shape. You didn’t have to worry about much at all: In a cult, you had it made. People *respected *you.

At the training meeting, we watched all the old videos, in which famous old affiliates, long graduated, cleared the cult hoop with *style*. I felt my toes pointing in my boots. I was anxious to prove myself. I was on *fire *with it. At the end of the meeting, the Big Kahunas looked at each other and took the big group of us jumpers into a small locked room in the basement of the culthouse. We were all huddled in the doorway—I went up on my tiptoes to see over the group in front of me. And there it was.

“Of course, it will be higher,” said the Big Kahuna. It was old and made of a warm brassy medal and extensively engraved. It was a small hoop—not more than three feet in diameter—but I heard they kept it relatively low down. This was good, because I was not very tall. It seemed like it would weigh a lot and hurt a lot if you messed up your jump and crashed into it. I looked back at the other jumpers. They were all shiny-eyed. Some of them were already in very good hoop-shape. I was going to have to train very hard, but I really wanted it.

I spent long hours doing the calisthenics the cult’s trainer recommended.

There are rumors that affiliates lower the hoop for jumpers they like, for jumpers who look like they would belong in the cult. I didn’t know whether to believe them or not, so I tried to dress like the affiliates and try to get the cult trainer to like me, just in case it helps. I got to know some of the other jumpers during our training sessions and we would laugh in hushed voices about the vocal tics of the cult trainer or the Big Kahunas’ pretensions during the Intro Training meeting. I felt connected to these other jumpers.

A couple days before the preliminary hoop, I cried over lunch with an older friend who had cleared a number of well-respected hoops. Sometimes around here it feels like everything's about who's jumped through what hoops. I asked why we even needed cults. If there were no cults, I told him, we could just*spend time together *and get to know each other in the normal way and not spend our time sniffing out who was worth knowing based on what cult they were in. He nodded patiently and told me that all of these things had occurred to him when he was a young jumper. This complacency made me terribly angry: Once you were enfranchised, once you were in, there was obviously no motivation to do anything about it. I imagined myself, suddenly, years down the line, a complacent affiliate, watching all these freshmen making the jump they’d trained for months for and missing the hoop and knowing they would spend another semester on the outside. Don’t let me be that person, I told myself. A small voice said, *But if you make it, of course you will be. *

I made it through the preliminary hoop, which was just like the final one but larger, easier, made of a flimsier and more forgiving material, and kept training hard. I watched my body change. I woke up to aching muscles I didn’t know I had. I dreamed about that final hoop. There it was, dusty, winking at me from the basement of the culthouse.

Final hoop day was less of a big deal than I thought it would be: They hauled the thing up into the big main room on the second floor of the culthouse and you waited in line until it was your turn to jump. You made it through or you didn’t, and then you landed.

When you're looking at a hoop—even a low hoop, even a hoop that everyone makes it through eventually—you're thinking a couple of thoughts. You're thinking that this hoop is the measure of your worth as an individual. You *know *that this isn’t true—you know that there’s a lot of chance and variables you can’t control that go into whether you make it or not—but you inadvertently can color the result as the ultimate reflection on your innermost self. Do I deserve this, you’re thinking, or you’re not, because you’re focusing too hard on the jump itself.

I made it, and I stuck my landing, thank god. The cult trainer and a couple of other affiliates marked notes on clipboards. A Kahuna carefully measured my final distance from the hoop, which was discouragingly small. Other jumpers had jumped further. There was some polite applause, and I was ushered into a room downstairs to wait with the other jumpers who had made it.

Because I was a freshman the cult swallowed me pretty cleanly—I didn’t have many strong attachments. After I became an affiliate of my cult, I saw those other jumpers—the ones I’d gotten to know who hadn’t make it—around the College. They didn’t really want to talk to me. It was okay: Suddenly I had a place to go, somewhere I felt a little bit special every time I walked in the door. The culthouse felt like it was a place of magic. It radiated out from the hoop stored in the basement, permeating everything we did and said inside the culthouse. I felt lucky to be a part of all of it.

A week or so after I made it through the hoop, a Big Kahuna mused that he was jealous: He wished he could be a new affiliate again. I stared at him, wide-eyed, and asked why he’d ever want that. Big Kahuna smiled and said that as a new affiliate, everything felt so magical and shiny and new. Over time, he said, with more responsibility, the magic wears out. I have a song for you, he said, and hooked up his phone to the speakers to play a song which repeated a single lyric to an infuriating beat. “You can normalize,” a voice said over the sound system, “Don’t it make you feel alive?”

I thought about that glowing hoop in the basement. I couldn’t imagine normalizing any of this. We have this notion that we can reach out and grab the self-assurance of affiliation and hold onto it forever. Really we can only take validation in doses. The feeling always fades, and then you need a little more. You find yourself another hoop, but there are always diminishing returns: Suddenly the same dosage won’t do it for you anymore. It’s like when you get stronger and suddenly the ten pound weight doesn’t make your muscles burn. You get something heavier. It seemed like if you wanted to feel like a real part of the cult, you had to be a Kahuna.

Becoming a Kahuna meant another jump—this time through the separate intracult hoop, which was a different deal entirely. This one was very large but was some kind of a polygon, a scalene triangle, they said, so it would be easy to guess the angle wrong and get stuck. The Kahuna hoop was set out annually and the jump was set to happen about a month after I became an affiliate. Luckily for new affiliates they kept the hoop pretty low. (It was higher, of course, if you wanted to be a Bigger Kahuna). I was still in good jumping shape and made it right through.

As a little Kahuna, I had new responsibilities.

I could play my own music over the speakers in the culthouse. Suddenly I couldn’t hear the different cadence in the voices of the Big Kahunas and couldn’t tell if I’d adopted it or not—it just felt normal. At first, cult-ural acclimation is confusing and weird and stilted, and then it’s natural, and then it’s just like breathing, and then you can’t imagine *not *doing those things. You can’t remember a time when you didn’t know to play this song or drink that drink. I *was *starting to normalize. There is something really satisfying about feeling like a part of a place just by knowing its little customs.

But that humming golden hoop in the basement just felt like an old hump of metal. For so long I had felt I was catching a glimpse of something furtive and beautiful that belonged to all of us, partaking in a set of customs and aesthetics decided by a Big Kahuna long ago. Now, another little Kahuna and I would play a certain song and then someone would ask for that same song a couple days later. We could do things that had never been done before, and affiliates might like them, affiliates might do them with us.

This was exciting, but it was also hard to be in awe of something we were making. I wanted that reverie back.

Suddenly I was on the other side of the Intro Training meeting. I was very conscious of this reversal, but it didn’t really feel like a big deal. It felt hollower from the other side: The affiliates at the table were all familiar faces. I wondered if we seemed intimidating and cool to the jumpers. I couldn’t imagine we did. We were just goons.

I was put in charge of training a couple of jumpers that Spring. I turned to older affiliates for training programs and held as many extra practice sessions as my jumpers wanted. I cared about them. Not one of my jumpers made it.

And then there are the would-be affiliates who were told from a young age that hoop-jumping isn't for them. Their bodies weren't built to jump through hoops, affiliates used to think. Moreover, maybe the hoops weren't made to allow their bodies through. This is a complicated problem which can't always be solved by changing the shape of the hoop (the shape of each cult's hoop is sacred, so sacred). From the inside, I badly wanted to believe that mystique and inclusivity were not mutually exclusive.

At the College, the absence of a cult can feel like a deep insecurity that leaves you open to a kind of death: the death of being just like everyone else. Or at the very least, it’s like being the only vegetarian at a BBQ restaurant or the non-smoker on the smoke break, except instead of cigarettes we’re talking about achievement-crack. I admire these people who do the College without it.

Sometimes I worry that one day I will be old with all of the spoils of my hoop-jumping career sitting around me and wish I had spent my life on something other than the stupid sport. I consider the arthritis some long-term hoop-jumpers get from the repeated exertion. I’ve already had one bout of this arthritis.

But the spoils can be sweet: the feeling of communal self-worth; a kind of special inclusion in something magical and secret; a humbling sense of one’s own privilege to be a part of the group. I think some of it also really does come from all those good things we talk about in our pre-jump speeches: from having a community in which to invest your energies, a thing you have come to care about altruistically, for its own sake. The big old world, from inside of a cult, was whittled to a manageable size.

I don’t think they’re mutually exclusive—the community-mindedness and the validation —but I worry that the latter is addictive.

I decide to go for a bigger hoop. A lot of people expect that I’ll have no trouble making it through—I’ve never missed, have I? I’ve done a lot for the cult and the Big Kahunas will recognize that and put the hoop lower.

I don't make it through the hoop. A tie on my jacket gets caught on one of the odd polygon’s corners and I hang there, half in half out, for much too long before they figure out how to get me down.

People normally don't get stuck. When they take me down, everyone’s sympathetic. It’s okay, they tell me. We’re still your family.

The other little Kahuna makes it through and becomes a Big Kahuna. I feel a little bit left behind, and then again, I’m happy for him. I’m happy for the cult; I know he’ll do great things as a Big Kahuna. But I’m sad that I won’t get to do them with him. I didn’t know how to look at this: The cult was in great hands, but those hands weren’t my hands. It didn’t need me.

These things are really fucking messy psychological experiences. They never sound good politically: In this article, I inevitably come across as overly ambitious or a traitor to my cult or allegiant to a problematic power structure. We talk about all this in such sanitized terms: Are cults objectively *good*, or objectively *bad*, for the College community as a whole? I think the real answer is much more nuanced—the structure as it is has oscillated between giving me a home and a sense of magic and breaking hearts (mine, others’). My time as a jumper and then as an affiliate and then as a Kahuna—an absurd trajectory which is completely illegible outside of the College—has given some meaning to my subjective and individual experience. I think there are conversations about these groups that aren’t making it into the discourse (the politically-incorrect, subjective, biased experiences of people inside and out, which get sterilized into strong political statements). I think we too often conflate ambivalent subjectivity with emptiness, uselessness.

Let’s end with a tally. I have gratitude for the strength I gained from jumps, successful and not, and gratitude for the family the hoop gave me. I worry about the way that love for the sport itself can tear this family apart. I worry about cult-ures of exclusivity and the lines (perhaps arbitrary) they draw between the inside and the outside. We dance across these lines (which make all of us uncomfortable, inside or out) with buzzwords like “inclusivity” and scathing op-eds and small acts of kindness toward our hoop-trainees. I think there are fulfilling ways to be in and around this cult-ure without hoop addiction. I am still trying to find them.

Features • Winter 2016 - Danger

I stood in the backyard in Berkeley (behind the tree, next to Marion’s easel and paints) and flicked off the little red safety.

Marion was inside, in our dirty kitchen, heating water for pasta while dicing sausage for sauce. *If I don’t come back in a few minutes*, I had told her, *something is wrong*. She had laughed at me.

I pointed the capsule towards the ground. I offered a licked finger to the wind, but it didn’t cool. It was a still July evening in the East Bay. *Check for a breeze*, my boyfriend Jared had told me, and then you can test it. *You won’t be able to use it when you need it if you don’t test it. *

I wrapped the capsule’s Velcro handle around my fingers, and pushed the trigger down.

Not much happened. A stream of liquid coursed out. Fixated, I held the plastic down a little too long, then pulled my finger up too slowly at the end—the fluid dribbled, pooled on the ground. A successful test, and now I knew. It only took one press of the button: brief, decisive. The packaging said the capsule contained 20 sprays, and that one had been worth maybe 2. At the end of the summer, I still had 18 left.

I flicked the little red safety on, and went back inside the house. I tucked the capsule into a pocket of my purse, easily accessible to desperate hands, and went into the kitchen to help Marion with the sauce.

***

The active ingredient in pepper spray is oleoresin capsicum, an oily resin that makes eyes burn and swell shut. It’s the same stuff that makes a good salsa. Last spring, chopping jalapeños for chili, I got a little juice on my hands and forgot to wash them. Thirty minutes later, after an absentminded rub of the eyes, I found myself bent double over a gushing sink, trying desperately to pry my eyelids open so I could flush them out. It felt like I was going blind. Even when I managed to force my lashes up, light and air made my whites and pupils sizzle, my vision blur. This pain came down to capsaicinoids, the compounds that make up oleoresin capsicum and determine its strength. The habeñero pepper rates 350,000 Scoville heat units. Pepper spray rates over five million.

A 1994 US Department of Justice report makes a strong argument for pepper spray as a weapon. It’s more potent than mace, affecting not only on the eyes, but the breath— inhaled spray swells mucous membranes along airways. Pepper spray rarely kills but almost always incapacitates, providing a viable alternative to guns and even tasers. Unlike tear gas, it works just as deftly on the drugged and drunk. It doesn’t linger on clothes; ventilation, soap, and water clean it right up. It’s great for riot control but banned in international war.

Civilians have access to the same caliber of pepper spray that law enforcement officials do. Sometimes it’s misused, but not often. Another Department of Justice report, last updated in 2011, documents 63 cases of death in police-civilian interactions where pepper spray was involved. Of these cases, most credited the cause of death to heart conditions or drug overdoses. In the few cases where pepper spray did link closely to victim death, causing positional asphyxia, it did so by exacerbating pre-existing asthma or other respiratory conditions.

***

I bought the spray last summer while working in the Tenderloin, a pocket of San Francisco named for an analogous neighborhood in New York City. Urban myth credits the name to a ‘hazard pay’ bonus for law enforcement officials, cash that the cops put towards fine cuts of meat. There are other namesake rumors: paid-off bribes (more money to eat well) and prostitute thighs (a different kind of flesh).

Bad things happen everywhere. This is what I tell my nervous grandparents every time I pack a suitcase. One gathers stray caresses in Prague public squares, shares bedrooms with suspicious strangers in São Paulo hostels. But men also follow footsteps in the heart of affluent Cambridge, and malls get shot-up in my own small Oregonian town. Really, no city is immune. One must travel anyway.

The Tenderloin’s statistics, while troubling, are brighter than Rio’s or Harlem’s. And yet, this place shook me; it scared me.

The first day I went into the office, I mistakenly exited BART a few blocks too far from the building. To get where I needed to be, I had to cut through Civic Center-UN Plaza.

Civic Center-UN Plaza is officially the home of the glistening San Francisco United Nations building, bounded on one end by a city hall on a hill. Unofficially, it’s home to a huge encampment of homeless men, women, and children. There are needles in arms, wheelchairs, rooted up trash cans, women in short skirts soliciting, women in long skirts screaming. There is hunger there, the pervasive smell of urine. Cops with large guns stand outside the government buildings, surveying the squalor with guns slung across their chests. It’s far from a slum. There are theaters in the Tenderloin, and restaurants, and schools. Still, it is something to break a heart: to watch the men with briefcases and women in blazers walking at a clip, brushing off need like a pesky fly; to crane a neck at those government palaces, looking down on their Americans with chilled apathy.

The first day I went to the office, I was wearing a knee length skirt. That day I would learn that this look was too formal for the office’s casual vibe—and also, that this was much too much leg to go incognito. I had my phone in my hand (big mistake) cluelessly staring at a map. By the time I got to the center of the Plaza, and realized that I should have traced the perimeter, it was too late to stop.

“Hey beautiful,” a man leered, lurching in front of me. Whistles sprouted from points on the square. The sun was bright. I vaguely processed, heart throbbing, that I was getting too much attention. Too many eyes were on my legs, and on my purse. It was 10 am (I had been asked to come in late that day) so no other employee was out on the street. I was being followed, surrounded. Stubble floated in and out of my vision, deep voices in and out of my ears. I tried to decide: Should I smile? Should I frown? Which would provoke less of a response? I made it to the door of the building, fumbled with the lock. When the surly security guard let me in, I was sweating.

My least favorite part of each day was walking to and from work. Sitting at my cubicle, time ticking towards 4 o’clock release, I would shiver at the screams wafting up from the sidewalk—the cries of one woman, the same each day. My second day, walking from office to BART with a fellow intern, I made eye contact with a woman sitting on the ground. She stood, yelled, and pitched trash at me, hitting the side of my face. I covered my head with my purse and power walked for the BART entrance. The next week, I watched a man pick up a needle and inject it into his arm at the bottom of the subway stairs.

To get to and from my house in Berkeley, I walked down Shaddock Avenue, away from the tourist ice cream shops and into quieter residential areas. A man got down on his knees and proposed, citing my smile and eyes as rationale for wanting to marry me. A man on a bike shrieked as he careened into my path, shirtless and wild-haired. Two men called out to me as I strolled to work; when I didn’t look back at them, they whispered “bitch, you bitch” and wove through the crowd to keep up with me. I picked up my pace. That was usually my tactic: move faster.

I hate to admit how scared I was—I, who carry a stamped passport, I, who know the tactics to defend myself—a poke to the eye, a knee to the groin—and the right words to yell—‘Fire!’ or ‘Get away from me!’—and the wrong things to do—no solo taxi rides late at night, don’t wear your flashiest jewels on BART, don’t engage anyone on the street in conversation. The experiences I catalogued were disconcerting, but I know (and knew then) that they were far from true horrors.

I felt elitist in my fear, petty for wanting to protect myself. These were people without access to toilets or nutritious food, people with yellow eyes and sallow skin. Most of those who yelled at me were obviously out of their minds—schizophrenics, or deranged from drugs. My fear didn’t strip me of compassion, but it did make it impotent. Instead of handing out bottles of water and Band-Aids, I was scuffing past the debris, secluding myself in a cubicle, getting away from it all at any cost. On the train, I thought about the Gospel healings—equating the lepers and spirit-possessed screamers of Galilee to the junkies in the Tenderloin. What a thing it would be to make illnesses jump into pigs, to make this nation well.

***

Pepper spray is legal in all 50 states. In some, like my home Oregon, that’s a general ‘go ahead;’ in others, it’s qualified. In California, I could order a capsule on Amazon, provided I was over 18 and purchasing less than 2.5 liquid ounces. Most of the regulations are of the non-minor, non-felon sort. Many states restrict carrying in public places like schools. Of course, abuse is a crime, and pepper spray cannot be carried onto planes.

When I returned to Boston with spray in hand this fall, a local told me I was a criminal, that you needed a firearms permit to carry pepper spray or mace in Massachusetts, and that you could only purchase them from a registered firearms dealer. That regulation has changed, though; the local was ill-informed. As of September 2014, a provision in a new piece of state gun legislation makes it no longer necessary to carry a permit to buy. (Massachusetts had previously been the only state with such a rule in place.) You still have to buy from a dealer, and you can’t order through the mail.

The other interns in my office carried pepper spray. My parents advised me to get some. But ultimately, I ordered a capsule of Sabre because Jared asked me to. He came to visit me for a week, walked my streets. We ate yellow curry in Berkeley, hiked from Ghirardelli Square to the Golden Gate Bridge. We also went to my office together. After his plane ride home, I received an email. It contained several links to Amazon pages.

*Please, please buy at least one of these. They cost practically nothing and they're a good investment for you even post-San Francisco, since you'll almost certainly be jogging and commuting in urban environments.I do think it will make you feel a little more secure and empowered. *

*I want you to get serious about learning to defend yourself. *

***

Growing up, my dad kept a baseball bat under my parents’ bed. He has retained all his muscles and used to play shortstop in high school. I have no doubt he could seriously wound or even kill an intruder with a few fell swings.

When I walk through a parking lot after a late night movie, I hold my car key between my fingers, ready to enter into an eye or slide up a nostril. In middle school, us girls sat on the gym floor with the physical education teacher and identified other common purse items that could be used as weapons: a comb, an uncapped pen.

My grandfather has owned guns all my life. He takes them to the Alaskan wilderness to hunt, hangs the heads of the animals around his pole barn.

But baseball bats are for baseball, keys are for driving, combs for brushing, pens for writing, and in this case, guns for hunting. There was something different about buying this spray.

What does it mean to carry something meant for hurting, and only for hurting? To carry it from a house in Berkeley, through the stiff air of the subway, down the blocks of the Tenderloin, into Celtic Coffee to get a Thai iced tea, and into a law school where women wear pearls?

On a practical level, it would mean simply this: if someone came at me with a knife, or a gun, or a bicep, on my way to work or going home or going out, I would have a few extra seconds to escape, to shout for help, to get out my phone and dial three numbers. And that felt good. That’s why women buy this little container of liquid: to keep us out in the streets, going to work for legal think tanks, and having fun with friends.

On a philosophical level, it felt strange, even wrong. Nothing happened to me that summer in San Francisco except those catcalls—at most, there was the incident with the trash. I always walked to work in daylight. I never witnessed any crimes.