Spring 2017 Issue - The Harvard Advocate

Features • Spring 2017

1.

When it started, Ms. Baker1 was talking about the aorta or the distance between stars and I was clicking my pen and looking at the empty seats. By this time the school day had settled into midmorning, but there were still four people missing. I was in sixth grade.

A third of the way through Science, Ms. Baker got a call on the class phone, and as she listened she turned her back towards us as if to shield us from the news. The class murmured versions of What’s Going On in a low rumble and in response she slammed the phone down and simply said “The train was late,” deftly executing a classic parental slight of hand.

At around 10:45, four kids staggered in and sat down unacknowledged. They sheepishly took out their binders and began scrawling notes, but there was something disorienting I couldn’t quite place—their pens lingered too long in their hands, a dullness clung to their eyes.

Ms. Baker went back to writing on the board but her lilting voice was just sound and behind me I heard someone whisper Are You OK. I looked over to see a girl with pigtails mumbling something to another girl in a pink Abercrombie hoodie, who in turn nodded and put her mouth right up to the first girl’s ear. I couldn’t hear what she said at first but as I leaned closer I just caught the end of it:

“If you looked close enough, you could see the blood.”

2.

There’s a list of every teenager who has killed themselves in the Bay Area in the last fifteen years. The website *Palo Alto Free Speech Zone* conveniently organized all 21 into a table that catalogs their name, date, and method of death. Sarah Riojas, 18, hanging. Cameron Lee, 16, train.

The only name on the list I recognize is Shelby Drazan, 17, traffic, since she went to high school across the street from me. I never knew her personally but I knew the story, or at least a version of it: There is a country club next to the freeway, and one day Shelby went there for lunch with her mother and grandmother. She chatted about school and listlessly picked at her chinese chicken salad or club sandwich before excusing herself to go to the bathroom. After about fifteen minutes passed, her mother and grandmother wondered where she had gone, peeking in the bathroom only to find that she was nowhere to be found. They wandered outside and saw a crowd peering over the guardrail, as Shelby had jumped off the 280 overpass into the traffic below.

I ran into a friend’s mom at Starbucks, who whispered this story to me with a lurid eagerness that said *you’ll never believe this*. I don’t think I do. But solid facts are hard to come by—even Palo Alto Free Speech Zone can’t help but evoke the imagination. Next to the strictly empirical name-date-death there’s a “notes" section for each person who died, which hint at a narrative by suggesting the reason behind the suicide (“it was not because of school or family pressures;” "fought depression all his life”) or constructing characters (“Equestrian. Dad: Venture Capitalist. Sister: model;” “Gunn basketball team captain & Merit Scholar”). Others are more opaque: one girl’s note only has a link to a photo of her grave, many of them have nothing at all.

2.

When people ask me where I’m from, I have my audience-tested Palo Alto speil about Stanford, about the google-glass clad tech bros popularized by the HBO show Silicon Valley, about the James Franco movie, *Palo Alto*, which I’ve never seen but appears to center around some sexy type of suburban angst which involves losing your virginity to your soccer coach and looking wistfully out a picture window.

But a few months ago I was at a birthday party at a friend’s apartment, introducing myself to someone's long distance girlfriend—a soft-spoken brunette studying to be a psychiatrist. It was the type of party where we clutched red solo cups and struggled to hear each other over the Migos blasting in the background, but because we were drinking gin and tonics instead of Rubinoff and eating dried apricots instead of Doritos we felt that the whole thing was very refined. When I told her I grew up in Palo Alto she responded by darting her eyes towards the floor and getting very quiet.

“How was the um…mental health situation?" she asked.

"What?"

“The mental health situation. I’ve heard it’s uh…" She paused to look at the ceiling, as if she’d find the right words between the rafters. “Like, did you read that article in *The Atlantic*?"

“Yeah."

“So did you know anyone who was involved in that whole…thing?”

She looked at me wide-eyed, expectant. This wasn’t the first time someone had asked me something like this; I’ll be at a birthday party or a friend’s family dinner and some nervous suburban mother or melancholic high-school overachiever will start speaking in a particular kind of code. Sometimes they will say distant generalities like *Palo Alto seems like an, um…stressful place to grow up *and expect me to read between the lines*, *other times they will ask pointed questions about articles in *The Atlantic* or the *SF Chronicle*.

That’s because Palo Alto has been launched into infamy as the capital of teen suicide in America, home to not one but two suicide “clusters:” Four dead in 2009, three dead in 2014, all teenagers--the majority dying by laying on the CalTrain tracks near the Palo Alto station and waiting for a train.

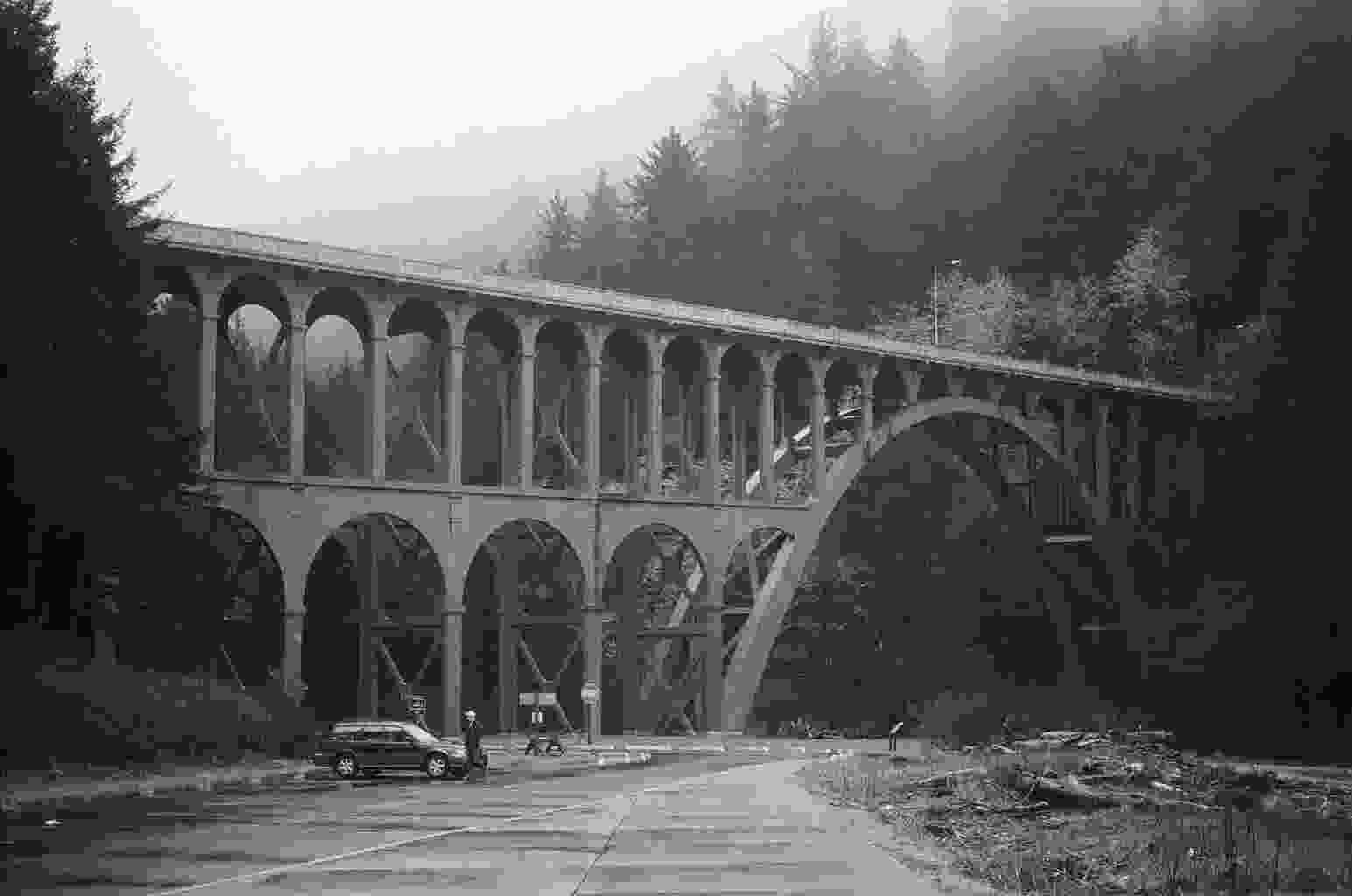

But this is not inherently noteworthy, as clusters of teen suicides are, unfortunately, not that rare. What gives Palo Alto its headlines is that it seems so inhospitable to tragedy. It has the typical quaint shopping streets and idyllic public schools associated with utopian suburban towns, but unlike the Stepfords and Greenwiches of America, Palo Alto has seemingly managed to phase out the backwards gender politics, the lethargy, the malaise associated with a more antiquated suburban ideal. Instead, Palo Alto oozes possibility— Stanford welcomes thousands of whiz kids into its stucco walls and the booming tech industry beckons siren-like as the seat of innovation in America. Trees curl around major thoroughfares; even the freeways look like they've been plucked straight out of a golden-hour soaked Bierstadt.

This gives the story of the Palo Alto suicide clusters a seductive quality, of the paradisical suburban town with a grisly underbelly, and these east-coast journalists and melancholic overachievers and affluent mothers all ask the same question: *why this town, why here?*

But the aspiring psychiatrist asked me a simpler question: if I knew anyone who was “involved in that whole thing.” I suppose the answer was yes and no. It felt duplicitous to claim that I had any real authority on the Palo Alto Experience, since I went to private school in Menlo Park, a town three minutes away. But, at the same time, my time in Silicon Valley was tinged with the two outbreaks: the first happened the year I moved, and the second happened my senior year of high school, right before I left for college.

“Yeah,” I told the aspiring psychiatrist, finally. “But um… it’s not like I have a ‘take’ on it or anything.” I clutched my solo cup a little tighter and shifted my weight back and forth between my feet. “I guess it’s just sad to be in a place like that.”

“Oh yeah, no, I totally get that,” she said, in a tone so deferential I almost felt like I should have been the one comforting her. We each waited for the other to say something more, but no one did, and, when the conversation had sufficiently deflated, she gave me a dignified nod and excused herself to get another drink.

As I watched her stumble towards the kitchen, I thought about one of my high school friends. She went on meditation retreats, and as such there were weeks at a time where no one could reach her. There was a year in which each time she left town to meditate, one of her friends tried to kill themselves— first her ex-boyfriend, then her lab partner in 10th grade Chemistry. She told me all this in trembling whispers, at three in the morning at a sleepover after everyone else had already fallen asleep. I knew her for eight years and this was the only time I saw her cry, tears splotching the edge of her blue nylon sleeping bag.

I wonder what she would have told the aspiring psychiatrist. The more I thought about her question, the less sense it made to me. What does it mean to be “involved” in someone’s suicide, in the first place? Would my friend say that the question of whether or not she was “involved” was one that haunted her, kept her up at night? Would she say that after her suicide year she didn’t go on meditation retreats for a while, because, in some shameful way, she felt responsible for their deaths just by being away? Can you even say something like that to a stranger at a birthday party without freaking them out? Or would she have just demurred, as I did, saying something vague and insufficient before letting the party swirl around her as if she were trapped inside the spin cycle of a broken washing machine?

4.

If you type the name “Nick Woodman” into a search bar, here is what Google will suggest to you: *Nick Woodman house, Nick Woodman net worth, Nick Woodman yacht.*

This is because Nick Woodman is a billionaire, famous for inventing the GoPro. He also went to my high school, and a few years ago he showed up at the school gym in the requisite chill-CEO uniform of a company T-shirt and jeans to receive an alumni award for his achievements.

He took a pointed, particular joy in returning to his alma mater because he was such a blatantly terrible student. He could point to each teacher who was still around from his era and explain exactly how the teacher in question hated him, and spent a good amount of his speaking time doing just that. It was clear Woodman came back to high school to gloat— he held up his plaque with manic glee and tossed GoPros into the audience like confetti.

Then he got to the meat of his speech, the GoPro creation myth: Woodman gave himself until 30 to invent a product and start a company, and if he failed, he decided he would finally try and get a “real job." After he drove his first company into the ground, he got the idea for the GoPro filming himself with a disposable camera while he surfed in Bali. To raise the funds for his venture he and his wife sold shells he found on the street, and, crucially, borrowed $230,000 from his parents before the GoPro took off and he finally made his fortune.

This speech was a standard grade Follow Your Dreams (Don’t Worry; Failure is an Important Part of Life) sort of narrative, but in the context of the suicides, Woodman’s speech took on a darker tinge. With no clear explanation for the preponderance of suicides in Palo Alto, the community landed on stress as the culprit. This might strike some as strange, as typically, stress is a temporary condition: something specific, usually work, stresses you out, and then, once you complete the task at hand, the stress fades.

But in Silicon Valley stress is treated as a constant state, an existential condition. The most famous evidence for the Silicon Valley stress epidemic, cited in all of the articles about the suicide clusters in mainstream publications, is an op-ed in the local paper called “The Sorrows of Young Palo Altans,” in which Carolyn Walworth, a student at Palo Alto High School, described the catastrophic effects of the stress crisis in lurid detail. She suggests that the crushing pressure to get into Ivy League schools steamrolls Silicon Valley’s teenagers. Because getting into college requires such overwhelming dedication to meaningless labor— studying for AP’s, filling out SAT practice tests, driving back and forth from brand-building extracurriculars—high school students feel like animated corpses, walking resumes. The implication is that adolescent life in Silicon Valley is so anxiety-inducing and life-sucking that it could drive a depressed kid over the edge.

But the piece is strange evidence for the Palo Alto suicide problem. Walworth only mentions suicide three times, and does so only to *distance* herself from the suicide clusters. While she says that she feels “nothing but empathy” for the depressed and suicidal, she maintains that “not all problems relating to suicide and depression are directly correlated to school.” The closest she comes to connecting the dots is when she says that if you’re already struggling from depression, being in a competetive, stressful environment “can’t help.”

Instead, this piece is masterful in its use of euphemism, of implication. Her depictions of stress center around melodramatic imagery of disease and death— she describes stress as a “physical pain," and "a fresh gunshot wound" that means kids are "gasping for air,” unable to "draw a measly breath in”—and waits for the reader to fill in the blanks.

I read this article right when it came out, in 2015. I was a high school senior at the time, steeped in the mileu Walworth describes—the grade-grubbing drudgery, the masochist machismo in bragging about how much time one spent doing homework at night. I’ve heard of a girl whose mom was so committed to her productivity that she would spoon feed her dinner while she did her homework, as if she were an infant, so as not to distract her from her work. My high school friends had achievements so improbable that when I describe them it seems like I just picked qualities out of a hat at random (i:e, mathematitician/judo champion/outdoorsman, pageant queen/particle physicist/poet). These accomplishments required a near-robotic level of discipline— if I casually mentioned an episode of TV I had seen the night before, inevitably, someone would respond in a nasally whine: “Wow, you’re so lucky—I don’t have *time *to do things like that anymore.”

But even I had trouble relating to her depiction of teenage life in Silicon Valley. It felt not only melodramatic but deeply crass to equate studying for the SATs in your affluent suburban hometown with a gunshot wound, to turn too much homework or a bad night of sleep into something fatal.

But even if this conflation of stress with depression seemed exaggerated, it reflected the way we talked about mental health at my high school, or, perhaps, more accurately, didn’t talk about it. If our we had any meaningful discussions about depression, I do not remember them, but when the second suicide cluster hit in 2014, we talked about stress with such frequency and absurd intensity that a girl in my class wrote a piece for the school paper titled “We Already Know We Are Stressed.” We had endless student-teacher forums about instating mandatory free periods or starting school an hour later to reduce student anxiety, while teachers spoke to us about the absurdity of college admissions, all the while repeating "stress does not equal success.” Nick Woodman was supposed to be a comforting reminder that you can spend high school surfing instead of studying and still end up a billionaire.

Like Walworth’s piece, these were never connected explicitly to depression or to suicide— there was always a level of plausible deniability. But I’d maintain that if you looked close enough, you could see the substitution happening—why else would we have obsessed over it so much? A week or two after one of the suicides, one of my English teachers began to cry in the middle of class, seemingly inexplicably, because she was worried about how stressed we were. The day after someone killed themselves my senior year, we had an assembly, and we wondered if the administration would talk about it. But they simply said “this is an especially stressful time of year, be sure to take care of yourselves” before dismissing us back to class.

Stress became a way of talking about being sad without allowing it to become a real, status-quo threatening Problem, a way of making depression easily diagnosed and easily solved. *Not getting enough sleep? Go to bed earlier. Too much work? Do less. *In removing the language for depression we traded one problem for another—a depressed kid could simply be described as “stressed,” and it would not technically be incorrect.

But when the kids who die look no different than those who don’t, it's hard to tell whose sadness is a problem and whose is merely matter-of-fact. I’ve seen two mothers, both of whom have depressed kids, feed each other euphemisms about their children “having a hard time” through pursed lips, without realizing that the other mother had gone through the same experience. One has to read between the lines, to look harder, *if you look hard enough, you can see the blood.*

5.

One day the whole school went out to the soccer field and saw a Buick flipped over, smoke coiling out of its battered hood. After a minute a football player from my Bio class crawled out of the car in a daze and gazed at the destruction. He seemed unaware of the audience around him, and spent a few moments wandering around the field sonambulant, before pausing as if to remember something. He bolted back into the car, launching himself through the crumpled door, and dragged a small girl’s limp body out onto the field. She coughed weakly as he laid her onto the grass.

He dialed 911 but his voice was overwhelmed by the small girl’s labored breathing, slowing before stopping entirely. The field was silent. The football player pressed his hand to her heart to check her pulse, but there was nothing there, and he fell to his knees and wept as the girl bled onto his lap. The paramedics came and loaded the girl onto an ambulance, but the football player stayed still, trancelike, his head in his hands. We watched him weep for what felt like too long. Then the paramedics carried him onto the ambulance, and they all drove away, the siren dopplering into the distance.

We stood there for a moment, tacitly asking each other, *was that it? is it over?* After a confused silence, we all walked back to class, and next week the small girl and the football player came back to school as if nothing had happened.

This performance was the culmination of “Every Fifteen Minutes,” a program designed to scare teenagers away from drunk driving by simulating fake deaths. Some of them were dramatic, like the soccer field car crash, but most were banal— every fifteen minutes, the Dean of Students would come into class and read a script that stated: “I'm so sorry to interrupt, but I have a tragedy to report. It has come to my attention that X died last night after a drunk driving accident. We are deeply saddened to lose him/her, take care of yourselves in this trying time.” Then the administrator would put a hand on X’s shoulder, bring him/her outside, and that was it— they were gone.

None of my teachers knew quite how to respond to these interruptions. The correct thing would be to play along. Some took a moment of silence. Others smirked at the pageantry of it or mumbled something chilly and snide. Most nodded solemnly before returning to the quadratic formula or The Scarlet Letter or the history of the Civil War.

They erected gravestones right next to the lockers, and students played death, stopping to mourn at their classmates’ fake graves, while the Dean of Academics dressed up as the grim reaper and wandered aimlessly around the school’s grounds.

At the time it seemed strange to me that we had spent so much time mourning fake deaths when actual deaths were happening seven miles away. Sometimes I wondered what it would be like to have an “Every Fifteen Minutes” for suicide.

But then again, “Every Fifteen Minutes” functions under a very specific logic: when teenagers see how scary it is to die of drunk driving, they will be more afraid of death, and because they are afraid of death, they will not drunk drive. In practice this logic didn’t exactly hold up, as in the world of “Every Fifteen Minutes,” there was a sense in which it was preferable to be dead than living. I remember being mildly disappointed I hadn’t been picked to die, as being dead became somewhat of a status symbol— there was a rumor that the administration picked which students died based on how much they’d be missed.

The administration was already somewhat worried about romanticizing suicide— they adhered to the school of thought in which merely mentioning suicide in a public setting asserted it as “an option,” and rendered it more attractive to those who were already depressed, so perhaps it was better that they didn’t transform it into a spectacle*.*

Besides, maybe it wouldn’t be so different. We’d still have the speeches of “take care of yourself in this trying time,” the creeping fear that someone you know might be next.

I still think often about the football player wandering around the field, listless, despondent. Even though we watched him from far away, I remember his face shifting while he watched the small girl die as this sense of deep, pervasive guilt descended upon him, this sense of *if only I could have known. *I thought of my friend with the meditation retreats who beat herself up for being away, knowing intellectually that it had nothing to do with her friends’ depression, but feeling gripped by remorse anyway. I recognized it in my classmates as we walked back from the field, as if we were carrying the football player’s guilt collectively like a weight tied to a bunch of balloons.

6.

When I was 12, Stephen called to tell me he had just tried to throw himself off a building. He was my best friend in middle school but I hadn’t seen him in a while — I got back home from sleepaway camp only a few days earlier. I was picking my brother up from the playground. It was one of those summer days so hot that you couldn’t tell what was exhaust and what was just air, and everything smelled like sunscreen and tar.

I paced back and forth on the blacktop with the phone pressed to my cheek as he explained to me what happened, but looking back on it I can’t recall anything we said to each other. The only thing I remember was being surrounded by screaming children and feeling like each child had a scream just for me. Later that night I turned the phone call around in my mind, wishing I had a speech for him about all the specific ways I loved him, but all I had was *I'm so sorry* and *I'm here for you *and all those words felt punctured, deflated.

If he had thrown himself off the building, he would have died the same year as the first suicide cluster. He would have been “involved,” to use the words of the aspiring psychiatrist— his name and age would have been catalogued in the table in the *Palo Alto Free Speech Zone*. Sometimes I wonder what his epithet would be.

But even as I’ve played a tape loop of our friendship over and over again I still couldn’t tell you why he wanted to die. Our friendship was based on doing bad British accents for each other and having impassioned arguments about whether the Arctic Monkeys or the Sex Pistols sounded more like sex. The only disoncerting thing was that he didn’t sleep much. He constantly skipped class to nap but always reassured me that he was Totally Fine, Really. When I asked him how he was he’d say: “I'm really tired, that’s all.”

This banality is the scariest thing about suicide. Ultimately, suicide is just a thought that won’t go away—it’s a dulling, a distance, a sublimation. It’s like trying to swim in a pool with no water, or turning out the lights at night and bearing the darkness at the room. What are you supposed to do with a pain you can’t see, a pain with no core? How do you know it’s there?

In trying to understand the Palo Alto suicides there is a sense in which we are circumventing this problem. When we ask ourselves why so many people die in Palo Alto, we locate the problem in a place rather than in a person. In some ways this makes things easier—it’s sociology instead of psychology. No longer do you have to reach through the murkiness of someone’s emotional life and pull out a story that feels plausible; instead we talk about patterns, statistics, stress, and work backwards to explain why someone died. Most popular suicide narratives function this way: the narrative thrust behind teen drama *13 Reasons Why*, for example, makes each titular "reason" for the main character’s suicide a physical tape that one studies, tracks, holds in hand. In making this move we remove depression from the caverns of the mind and transpose the source of pain outside of itself. It gives pain linear progression, a face, roots.

But I think that, in some ways, this move is the problem. Palo Alto is not a sadder place than most places. To argue that it is would be ridiculous; even among other affluent communities, Palo Alto doesn’t have a monopoly on depressed try-hards. Children of the meritocratic elite overwork themselves all over the country, from Andover to Los Angeles, and they’re not throwing themselves in front of trains.

The Palo Alto suicide clusters create a paradox; when so many people die in the same place, in the same way, it seems irresponsible to ignore the correlation, but depression is a tautology—no matter what the stories say, the depressed aren’t suicidal because they weren’t loved enough, or because they did not get enough sleep. They are depressed simply because they are.

Perhaps what makes Palo Alto a habitat for suicide is not that it is sadder than most places, but the opposite. With its golden-hour sunsets and oozing possibility and near-constant chipperness, Palo Alto is not a particularly easy place to be depressed. One feels like Walworth in “The Sorrows of Young Palo Altans”— melodramatic, crass, complaining too much. Much easier to sublimate it, to dismiss it as “stress” or transform into something more palatable.

But when nobody has the language for sadness, depression becomes harder and harder to diagnose. We wait for definitive proof, as if there were some way of deducing that someone's pain is *real* depression and not just run-of-the-mill anhedonia. But soon it’s too late: we get the call on the hot blacktop, we see the blood on the tracks, we cry, we go home.

7.

After that day in the summer Stephen moved to another school, and slowly we stopped seeing each other. We became friends only nominally. We’d often run into each other at a supermarket or a Starbucks and exchange stale pleasantries like *I miss you* and *we should hang out*, but somehow, we never did.

Finally, one day we decide to go the beach. We get burritos from the taqueria down the street and smoke. We’re both somewhat surprised to see how easily we get along, even after so much time apart, and we spend a while trading quips about the music we’re listening to and anecdotes about our boyfriends. But eventually the conversation turns to mental health, and cautiously, I ask how he is. He tells me he has an official diagnosis now, and that he has gone off medication, but that his boyfriend has helped tremendously. He tells this story in a practiced way, so quickly, and with such a pat, happy ending it almost feels flippant. But I tell him that it’s good to hear he’s feeling better, and he smiles weakly before changing the subject.

As we drive down the winding path towards the beach, the radio gets vague and staticky, so Stephen shuts it off. In the few moments of silence I watch him drive and think about the time we took a Drama class together in middle school. We’d play this game, “Mirror, Mirror.” It’s pretty easy: one person matches the other’s motions until they move as a unit, so no one from the outside can tell which one was leading.

I was never good at this particular game. I moved too abruptly, so it’d be obvious I was calling the shots. But Stephen was much better—his trick was to close his eyes. As his eyes fluttered shut I would have to close my own eyes in tandem, and then he would take my hands and lead a slow, blind dance. You can get into sort of trance when you are so mutually attuned to each other. Sometimes we’d even take on the same breath — four seconds to inhale, eight to exhale.

There is something beautiful about this kind of closeness, a wordless, edgeless empathy. How nice it would be to play an endless game of blind mirror, to eternally hold each other in hand. How nice it would be to share a breath.

1 To protect the privacy of the people mentioned in this piece, I have changed their names, genders, relationships, and details, aside from those of public figures (Drazan, Woodman, Walworth, etc).

Poetry • Spring 2017

I tried, you know, I wanted to,

I got a couple of volumes, three

Or four, and I didn’t do

Anything, years, so I rolled it

Up and went, went and un-

Rolled it, got to a friend,

A warehouse, a treatise saying

Years of goodbye, it went on.

I tried to be over and of course,

In vain, I found it, a shore,

Completed it and it died,

I mean something sticks, I did,

Meanwhile sleep, you know,

Drenched or silent, an ash

Presented and taken away, years

In that little wrong boat

Gotten so that I might give

With much and forever, nevertheless

These things carried along

Poetry • Spring 2017

What is language is a new needed

For the going on part of the end

You can tell has made it here because

The air is with condition

The outside seems to be like anything

Placed in a lab or subway car

The truths are showing through

The people have chosen to be

Each moves along fresh tracks

On the erasable surface

Toward a tiny destiny

Wearing vraiment raiment

It’s maybe three days after

Or exactly during seeing

The future put on its certainties

I want of the opposite to speak

To say what isn’t etymology, won’t

Be money to the king above my eye

Reach out to the invisible third

Among every two pedestrians

Where belonging bucks its norms

Difference lives in the least places

Shine caught in the multiple

Lie of any kind of hair

You can’t tell if it’s order or not

To follow the too many paths

Just above the face, below sky

Long enough to forget or be

Distracted from the big geographies

Where truth first learned of us

In the pit of an education

In the skysick life of power

In its moving rearrangements

I was walking on Mission Street

In love with you while damage bloomed

The right order right in the words

Below the preserved fade of marquees

The little sale of needless things

Listing bodies listed just past

It was far too easy to get here

Standing still while white time flowed

Around its professional mourners

Comfortable in end after end

The next one isn’t very pretty

At least we’ll see how together

It provides absent alternatives

My plan to put my body between

Where it already was and is going

Poetry • Spring 2017

He is Blot

it is a name

and down the street

he walks with

his name to a

house of timber

frame with a door

of mirrored glass

that he raps.

The quavering pane

buzzes Blot’s reflected

edges turning

temporarily to mud.

Highest definition

of self then resurrected

an aquiline vision comes

twinkling out of the

stiff staring well at

the front of the house

by the corded bell

he didn’t notice.

His body is many

predated little creatures

he tracks—each

he knows and smiles at

from flight high

over this mirror

his empyrean head

lofts always over

every mirror welling

like quicksilver kettle

holes one after another

sending back Blot

tilting his shades

or Frenching a smoke

or Blot naked

admiring the quilled

vasculature of his

mammalian wings.

The bird of prey

surveying its own

body is the child

Moses fondling rushes

tufting by the bend

awaiting the one

who will take to him

the architect’s own concept

and relish the saw work

the sanding and the

double coat. Blot

craves only an eye

a Cyclops all head

and no body. The

mirror swings suddenly

inward and the

frame blinks a black

lid ruptured by

a silver shooting

pit bull gnashing

artifice to spark

Blot hauled like metal

hanging from a bus’s

underside to the curb

and left possumed in

the dark rush of cars

no taller than bolted

hubs inch-near

in passing

Poetry • Spring 2017

A splitting tree stands wind-shook by

the slender trees swaying lost branches

scarred low on their sides, stands

lately deciduous, weighted thin

with first fall. Along Sha Wan Drive

towards the pool the yellow oleander

flowered like wet tissue ceaselessly

like paper rain, the grained cement

the yellow, yellow oxidizing white

the dogs you’d muzzle not to let them

have a taste. My mother takes us

to the pool, it’s maybe June, canary

petals landing on our heads, my sister

small enough she wears my t-shirt

for a dress, the cinder is so slick

with petaled rot—it used to seem at least

a life so deadly might not ever die—

my mother catches a heel, falls

she sends us both ahead to wait for her

thirteen years ago up past the trees.

If we could be there still perhaps

I’d run to her, kneel in the dappled light

piece the foot together from concrete

although we are each different women now.

Up here the whitened apples nod on trees;

shrubs waste to burgundy anemone in snow.

All that grows leaves is breaking

all splits at root. Some mends. I’ll watch

those slim arms birth entire skies of buds.

Behind me at the gate in the warm rot

my mother, foot stuck in a gutter, stands

and all her pain is yellow blooms.

Poetry • Spring 2017

On this day of our choice

we have collected

at forests like

some insect

varietals

beetling their way

to the heart of

the copse. We have

coalesced for

the moment as

dewdrops do

bivouac in the

abdomen of leaves

pooling tensility

against atomizing

sun or its reflection

sprung from mica

pieces studding

the sharp loam.

The tenderfooted

will wince

the shod shall

advance this day

of our choice when

we pass separate

through the wood

to track in packs

paths whose blaze

is merely what

we toss ahead.

All hopes into

mouths of our

beer cans are fed

crumpled jettisoned

and come upon

twenty yards

down the trail

as though left

to augur for

us there. But

no other has

before stood

here with legs

spread open as

a pair of shears

pin-stuck in the

soil like sign

of a miracle.

Here the trees

are deplumed

limbs mangled

and gray like

stone jali hiding

others gone other

ways this day

of our choosing

foreshortened to

evening already.

No two paths

cross and were

they to they

might as wires

sparking this

night of our

choosing to fire

but uncovering

a charcoal plain

across which we

might see one

another again.

Fiction • Spring 2017

When he suggests you try the pillow trick, laugh. Instead, tell your sister where you’re going. She’ll offer to cover without you needing to ask. Make her swear not to tell the parents. Don’t think about a world where she tells the parents. Don’t think about a world where they check both beds. Think about a world where they check both beds, consider the options: an inflatable you-sized dummy. A stunt double. An actor, not only to sleep in your bed; but wear your clothes; take your classes; let the parents stick report cards on the fridge.

Fiction • Spring 2017

I was slain by the spirit when I was only ten years old. This is not a story. This is not hyperbole. This is only the fact of a hand I can see and resee whenever I need to—a nun’s hand, looming softly, rippling towards my face as if on the quietest gust of candlelight. This is the last thing I remember before passing out.

Fiction • Spring 2017

Outside the Lighted Window ∙ (1919, 2013)

They sipped cereal milk from their breakfast bowls while discussing the men his wife might consider dating when he would be dead, and the overall feeling was that younger would be best. More energy would be nice, their daughter added. Their son pointed out that the difficulty with young was that the young too frequently found themselves poorly capitalized. He looked at his son as though he were looking through a wine bottle. The boy had always been a shit person, even as a young child, and he found himself authentically surprised that a person could change so little over so many years. Perhaps a dancer, he suddenly offered the conversation. His wife made a face that seemed to suggest she liked the thought of dating a dancer, as he’d felt she might. Then he saw her look off to a distant place, as she sometimes would in those years. Perhaps, she reflected aloud, we place too much emphasis on the present moment.

Archived Notes • Spring 2017

*The ball shall be a sphere formed by yarn wound around a small core of cork, rubber or similar material, covered with two strips of white horsehide or cowhide, tightly stitched together. It shall weigh not less than five nor more than 51⁄4 ounces avoirdupois and measure not less than nine nor more than 91⁄4 inches in circumference. *

*–– 2016 MLB Official Baseball Rules *

Every professional baseball you’ve ever seen slammed across the diamond or fall into the hands of a desperate fan has been coated in a thin layer of mud from a small waterway in southern New Jersey. Each July, armed with seven 35 gallon trash cans, one Jersey family makes their way to the secret stretch of water and harvests the next year’s supply of baseball mud. And each new season, baseball umpires meticulously **[rub](http://baseballrubbingmud.com/mud1.mpeg) **their balls in it before every game. The reason for this peculiar cultural ritual dates back to a seemingly obvious idea which only struck American baseball in 1920 –– that a baseball loses play value over time, that it gradually becomes worse at its job.

At least, this was the logic which led Major League Baseball to bring a period, later called the “Dead Ball Era,” to a close. From about 1900 until 1920, American baseball was a wildly different sport ––the teams reused their balls. A ball was usable until it began to disintegrate; at times this could amount to a lifespan of several hundred pitches. With more play, the balls became malleable, and this softness had a major impact on the game. Balls were hard to pitch, and even harder to hit for distance. Home-runs were scarce and scores were low. To win games, players relied on strategy, rather than power. They stole bases or became experts at “the inside game,” an offensive strategy to keep the ball in the in field, which included moves like the “Baltimore chop”–– a hard downward swing that sent the ball just in front of the plate. Runs were a rarity: in 1908, the season averaged 3.4 runs per game, its lowest average in history; in 2013, the average was 8.33.

The logic behind recycling was cost-related. Teams were so strapped for cash that fans had to throw balls back on the rare occasions they made it to the stands. Over the summer of 1920, American League1 president Ban Johnson, a squat, bespectacled man whose swatch of hair behaved much like the head of an overused toothbrush, got wind that his umpires were throwing out more balls than they could easily afford. Johnson insisted in a league-wide notice that the umps “keep the balls in the games as much as possible, except those which were dangerous.”

Only a month later, on August 16, 1920 in the middle of game between the New York Yankees and the Cleveland Indians, Yankee’s pitcher Carl Mays sent a ball straight into the head of Indians shortstop Ray Chapman. Chapman never moved to dodge the ball. Commentators assumed he hadn’t seen it, but they never had the chance to ask. Chapman died the next morning.

Mays, a sour and widely-disliked man, whose pitching motion Baseball Magazine once described as “a cross between an octopus and a bowler,” later explained that the ball had been a “sailer.” Mays had a reputation for unusual delivery2, but this time, his aim had been skewed (sending the ball “sailing”) by a damaged spot on the leather surface. That year, Kenesaw Mountain Landis, a tight-lipped Andrew Jackson look-alike and the first ever Commissioner of Baseball3, instituted a rule that balls be thrown out at the first sign of wear, heralding an era of newness in baseball paraphernalia. Unused balls would have smooth, sail-resistant surfaces and bright white leather, so they would stay visible even at top-speed.

But novelty wasn’t all Mountain Landis hoped it would be –– the dawning of the “Live Ball Era”came with its own problems. Baseball teams quickly discovered that the factory-issue balls came with a slippery gloss, making it hard for pitchers to grip them as they threw. All the experts call it that ––a “gloss,” sometimes a “slick”–– which conjures the image of a vaseline-like sheen, a layer of some substance coating the balls and making them hard to hold. But it wasn’t that. The players couldn’t wipe the gloss off, just as the factories couldn’t stop making it. The gloss was just the sheer fact of the balls’ newness, the slick of something never worn in. So almost as soon as leagues discarded their old balls, they began intentionally aging their new ones.

For a while, the purposeful “wearing-in” process was carried out with a coat of tobacco juice or shoe polish or just regular dirt –– anything to break the balls in and make them easier to hold. But each of these cures came with its own problems. Overly grainy dirts could distress the leather, recreating the old-ball effect; tobacco juice discolored the balls beyond usability; and in the heat, shoe-polished balls quickly acquired an overpowering stench.

Enter Lena “Slats” Blackburne, a retired player for the Chicago White Sox, who was coaching the Philadelphia Athletics in the 1930’s, where he overheard umpires complaining about this gloss. Blackburne had grown up on the South Jersey waterfront, home to a mud of particular consistency. He had plopped through the sticky mire as a kid, when he went fishing and swimming. And so it was to this old watering hole that the retired in elder returned, decades later, to harvest a handful of South Jersey mud. Blackburne brought a sample back to the Philadelphia Athletics Clubhouse, started experimenting, and soon found that he could remove the gloss from the baseball, without damaging or discoloring it.

Jim Bintliff, a South Jersey family man with a gruff, kind voice who now runs Lena Blackburne Baseball Rubbing Mud, the distribution business Blackburne started almost eighty years ago, describes the mudding process as something like the movement which precedes a pitch.

“You would dab your finger in the mud and just get a little bit on your finger, put it in your palm and rub your palms together, to spread it out. Take a drop of water and make it a little more liquid and then you just massage the ball,” says Bintliff. “You know like when the pitcher gets a new ball from the Umpire, how he rubs it around in his hand? That’s what it is. It’s that exact motion.”

The mud, which the company’s website describes as “a cross between chocolate pudding and whipped cold cream,” took off. By 1938, Blackburne was dealing to the entire American League.

He was not, notably, selling to the National League –– the other major league in the nation, against whom American League teams played in every World Series. According to Bintliff, tensions between American and National Leaguers ran deep in the 1930’s and Blackburne was an American League loyalist who refused to sell to the other side.

“At the time, they were mortal enemies. I mean, there was no love lost between the American and National League. They were completely separate,” Bintliff explains.“If you played for one, you didn’t hang around with guys from the other. The World Series was like a battle.”

This particular rivalry may have been speci c to Blackburne, as many other players had inter-league friendships. Still, without Blackburne’s consent, rubbing mud was off limits to the National League –– he had never shared his harvest spot (even today, according to Bintliff, the location is known to only a small handful of family members). So for over a decade, the two Leagues played with wholly different balls: the National League with glossy, factory-issued ones (perhaps mucked with some amateur substitute); the American League with balls aged by hand using Blackburne brand mud4.

Tensions eased in 1950, however, when Blackburne took a new job as a third-base coach for the Philadelphia Phillies, a National League Team. With one job transition, the entire game changed for the National League. Blackburne’s rivalry subsided and his brand became the gold standard of American baseball rubbing mud. Today, Bintliff says, the company sells to the entire MLB and their minor league affiliates, to all the independent leagues, to several colleges (including Harvard) and high schools, and even to a few teams in the NFL. It is now written into the MLB rule book (Rule 3.01c) that before every game the umpire has to rub down six dozen balls to get the gloss off. Nearly everyone in baseball coats their equipment in Blackburne’s mud –– they aren’t required to use his specifically, but for over half a century most teams have.

When baseball season starts back up on April 2nd, umpires across the U.S. will crack open canisters of South Jersey shore mud. One would think, in a culture with its eyes fixed on the next new thing, someone would have gured out a short cut, a way to manufacture new balls, already worn in. But no other treatment, mechanical or manual, does the aging job as well as Bintliff’s mud. The contemporary american baseball is both manufactured and mudded down before every game, and so occupies a kind of liminal age –– just past too new, but not yet overused. It’s a subtle timeframe. According to Bintliff, if rubbed right, you can’t see that a ball’s been aged at all.

“The umpires rub them, they put them in the box. They get through a dozen, then they go back and rub back over them after they dry to make sure there’s no dust or no cake build up on them.”Bintliff says. “And if it’s done right, you can’t tell that it’s done, if it’s done right. The only way you can tell is in the difference in the grip.”

1 An association of teams which includes, among others, the New York Yankees, the Boston Red Sox, and the Chicago White Sox.

2 Mays was known as something of a “submariner,” or a pitcher who elects to throw side-armed and very low to the ground, rather than the conventional, overhead motion.

3 The Commissioner of Baseball had been created earlier in 1920, to serve as the chief executive of Major League Baseball. The position had been determined necessary after the “Black Sox Scandal” –– when it came out that the Chicago White Sox had been paid off to throw the 1919 World Series to the Cincinnati Reds.

4 Notably, but perhaps incidentally, during these years the American League outperformed the National League in both World Series and All Star Game results.

Archived Notes • Spring 2017

In 2013, Tom Berninger released the seminal documentary *Mistaken For Strangers*: a chronicle of his brother’s rock band, The National. It was a film about a band, or, about a band of brothers, or two brothers, fighting. The film is a personal narrative about two brothers, not a band, but a banding together.

Tom Berninger is jealous of his brother and band-member Matt Berninger because Matt is a rockstar, famous and successful, while Tom lives at home with his mom. They embody the tension between the similar. Why is Tom not a copy of Matt?

Much of post-Y2K America can be gleaned from this work: the latest rise and fall of rock, the struggle of man in a harsh land, the tension between brothers, across states, as the one secret subject of a banking crisis that would be realized a mere nine years after the band’s formation.

***

Nirvanna is a brand new Nirvana1 cover band with a Kurt Cobain impersonator frontman, self-nominating as “the #1 tribute to the greatest grunge band of all time,”2 and a flawless recreation of the “iconic look and sound.” They sound pretty close to the Nirvana. They play the same songs. The impersonator looks like Kurt in the right light. But, this Cobain is too heavy to be from the nineties. The other two look nothing like the old other two of Nirvana.

Just this February, Nirvanna hit the House of Blues in New Orleans, turning the city into their own “Mardi Grunge.” This column is their coverage: a dissection of the fifty pounds this impersonator Kurt has gained since Nirvana last shredded America’s values in 1993; a critical conflation of this band with Berninger’s *Mistaken For Strangers. *The brother’s of The National are marked by their similarity. From it arises both their hatred and themselves. Everything is about this The National documentary, yet, in a way, it also is not.

There is something unsettling about Nirvanna’s renaming. Perhaps it is a deep similarity of language and letters with a resounding lack of semantic continuity. The name sounds and looks quite similar, but the additional ‘n’ entails that it is no longer ‘nirvana:’ it is neither a symbol for the meditative state, nor the band . In “The Doctrine of the Similar,” Walter Benjamin posits

*Nature produces similarities— one only need think of mimicry. Human beings, however, possess the very highest capability to produce similarities. Indeed, there may not be a single one of the higher human functions which is not decisively co-determined by the mimetic faculty.*

Nirvanna’s choice to imitate is not novel, but rather a choice to which we as humans are possibly predisposed. Their self-expression is merely the expression of capitalizing on a trope: namely, the trope of Nirvana. But can something new be found in their, presumably, conscious similarity, in their decision to express, in a seemingly original fashion, the expressions of another? No, “it might not be too bold to presume that on the whole a uniform direction can be perceived in the historical development of this mimetic faculty.”3

If what it is to be human is to be original, then only a continuous progression towards the unquestionably original can be assumed. However, this does not refer to an indeterminate and indefinable original, but instead to an Abrahamic sin-based conception of the original. Can the mimetic progression of Benjamin’s projection be one of both assimilation into the past and exploration into the future? Can Nirvanna both become Nirvana, escape Nirvana, avoid its impending battle with its brother, and be its own music by practising the similar?

***

After several viewings of the recent rock-documentary *The History of the Eagles*,and with its corrosive elixir of irony brewing in the back of my mind, there, the cover band Nirvanna began to slip, in and out of conflation, with the brothers of *Mistaken For Strangers.*

Nirvana and the grunge movement represent the 90’s desire for originality, for individualism in the individual; The National documentary is documentation of a man spiritually murdering his brother, the relation by which he both is and is not his own boy. These cultural artifacts are emblematic replications of the originals, to which the originals offered no foreshadowing. But also of sin. This move in the 1990’s to American individualism was a movement towards depravity, towards grunge, Lewinsky, and the computer-based techno-panic, a prelude to Y2K.

Increasingly, liberal America has forgotten that it, too, is constituted by sinners; that each and every man is born with original sin. People think that to own original sin is to sin in your very own way. Many think that they are not a product nor an aspiration of the similar. Yet, original sin is the timeless sin, the universal sin, and has nothing to do with post-Y2K originality, irony, or sincerity.

Nirvanna is original in the way we think our sin is not but is. It is original as traced back to the beginning— never new or naked, but simply exposed in its uninventiveness. The turn of the millennium, Y2K, has not brought us sweet sinlessness— but rather, its has made us forget that each of us possesses original sin. Our grunge movement was not a rebellion, but a Catholic Crusade. It was the hunt for the inner individual, for the self, for Kurt Cobain’s vapid aspirations. This was grunge, it was original, was the never-before. This was also sin: the sin of heroin, of the murder of Courtney Love by proxy of Kurt Cobain. Yes, there was a suicide; however, it was Love who killed herself, not Kurt, but through Kurt. Moreover, this was the same: Nirvanna is Nirvana, and even Nirvana was not Nirvana. Nirvana itself could only be original as it relates to the similarity of sin. They commit the same sins in the hunt for individualism, and even their suicide, their climax, was an act of proxy: an act through another, through the similar.

Nirvanna is the emblem of our post-Y2K existence, of our denial of our sin, of our Catholic guilt. They are sinful, full of lust and greed and pride for that which is not theirs: Cobain’s music. They are sinful. Yet have no ownership over their own sin.

We as contemporary Americans pride individualism, but we have perverted our original sin to be sin we believe to be original, sin that we think is not fake or lacking in uniqueness. This is the post-Y2K: the individual, the original, the identity, the personal. But it is not original. Another ‘n’ wont change anything. This is Nirvana still.

Maybe it is just that Cobain never died. A man, a proxy, a figment? Maybe he was a proxy, a hired hand, in own his death. We know he was a proxy when he was married. And so was Love. Maybe we have on our hands the same Cobain, having disappeared for twenty years and gained 50 pounds. He is fat, but he is also himself— he is Kurt-and-fat— and covered in a thin film so as to replicate the process of birth, and by proxy, the process of documentation.

Somewhat little known, and allegedly replaced, rocker Andrew W.K. has, admittedly, never been the same man. And as he says, he never feels real, or has never before felt quite so real. So why must we demand so much of Cobain? Because Buzzfeed does not know what is original, and neither do our concert goers. They do not know the sound of “Pennyroyal Tea”, or know that it hurts to see you Kurt, again, after so long.

Our perceived sinlessness is sinful. Our perceived originality is a cover band. Our means of crying out is unoriginal, and sinful. So it is sin. And the only sin is the original sin: that with which Adam and Eve left the Garden. Thus, it is not new, but it is original, and so infinite. Just as the deceased Cobain occupies the threaded needle of the infinite, so must Nirvanna, for its unoriginal originality is its very timelessness. Going out of fashion never will.

Yet, it is as well the symbol of our amnesia. We have forgotten what is original, what is the true Form, who is standing in the tall grass, why we are replicas and simulacra, which band is a cover, that Kurt is no one’s brother, that the first documentary was about The National, and that the New Age is one of sin (the same sin), the first sin, the original sin, the genetic and replicated sin, of the grunge ideology repeatedly breaking open the same punk-freedom riffs and rifts at each step, each time the clock strikes the next generation, each time the golf ball hits a hole-in-one, in our sinful genealogy.

***

But what can be gleaned from the similarity of these bands (and these brothers)? Is there something to read into this, or out of it to read? The nature of our new sin and new originality is determined only in so far as we can be certain that it is the same. Yet, there remain two ways for us to comprehend the novel originality that erupted from Nirvanna and The National, two means by which we can read into their cultural footprint. Benjamin, again, conceives of such similarities and their readings in these terms:

…This non-sensuous similarity, however, reaches into all areas of reading, this deep level reveals a peculiar ambiguity of the word "reading" in both its profane and magical senses. The pupil reads his ABC book, and the astrologer reads the future in the stars. In the first clause, reading is not separated into its two components. But the second clarifies both levels of the process: the astrologer reads off the position of the stars in the heavens; simultaneously he reads the future and fate from it.

The word ‘Nirvanna” as a symbol is understood only in its similarity, its subtle difference yet inclination to the mythical state and the grunge group, for it means nothing in and of itself. It is a symbol that can be listened to, heard, and read. But one can read more than that. Benjamin’s astrologer reads into the stars the future. Into Nirvanna we can read the past, though we may not want to. Because it is merely a reiteration of the same similarity, the same sin, we can read in it the past as reaching the entire way back to the Garden of Eden. Thus, though unintentionally, it is a crusade, as alluded to above. We can reach the tranquil state of understanding that there no nothing novel and interesting in our movements towards the self, the identity, or the individual, to our movements toward grunge, freedom, or self-expression. All that may be contained in these cultural shifts is a repetition, is the similar, is the the most general, frequent, and defining trait of human: namely, to aspire to the similar. And this similar is sinful. And like the sin with which we were all born, the similarity can be traced back, without genealogy to one event. The death of Cobain. For without this, there could be no impersonator, no inter-band tension, no gripe from which to build a feud or a documentary.

Nonetheless, Kurt Cobain is no longer Kurt Cobain. To cover a band is original only insofar as it is what has always been done. The Pitchfork review will say that Nirvanna sounds too much like Nirvana crossed with Creedence Clearwater Revival and with a drizzle of Danzig, too much like a bowl of sound mixed with a mixer that is Minutemen, while all painted on a canvas stolen from Can, running with a vision stolen from Television. Faux-Cobain is too hefty for his role as Kurt. They, Nirvanna, are the modern sinners, filmed live on documentary. The other two members look nothing like Cobain’s flank-mates. We go to concerts of the cover band because we have forgotten what original means, or because precisely we remember. Our sin is the same sin, and yet it feels so new. This film is still, and has always been, about The National.

1The renowned 90’s pacific northwest grunge band

2 Nirvanna— A Tribute to Nirvana, Facebook Page Biography

3 Benjamin, “Doctrine of the Similar”