Winter 2013 - Origin Issue - The Harvard Advocate

Features • Winter 2013 - Origin

This story was originally written for a national magazine at the turn of the century but never printed. In the intervening fifteen years, regrettably if inevitably, some of the participants have died, elders being the repository of communal memory. I have made no note of this fact, nor of any other events of the past decade and a half. The article is printed here, all but unchanged, a sort of literary bogman—or like the Advocate itself.

– D.T. Max ’83

Features • Winter 2013 - Origin

Sometime last spring, I was driving through northern Minnesota when the road I was on passed over a small waterway. It was an unremarkable little brook lazily worming through the forest, but a sign on the shoulder identified it as the “Mississippi River.” I pulled over and reversed back to the bridge in an extended double-take. There it was, though. The mightiest vein of the continent. From here it would grow dramatically as it moved southward and its tributaries flooded in from across the country, giving life to Minneapolis, St. Louis, Memphis, New Orleans, and countless settlements in between. But up here in Paul Bunyan country, it was just an unmajestic trickle. It was oddly thrilling to see so mighty a river in such an undeveloped and vulnerable state, almost like walking in on a head of state without his clothes on. Without much further reflection I drove on, inflated by a sense of having been granted a window into the inner life of the Mississippi River, a feeling that I knew it better than most because I had seen it like this.

I grew up in central New England and have no great ties to the Mississippi, so several months later it seemed like it might be a meaningful pilgrimage to visit the headwaters of my region’s primary river. I would travel up to the border of New Hampshire and Quebec, where rain- and melt-water collect in the four Connecticut Lakes before taking the form of the Connecticut River and flowing 407 miles south to the ocean, plummeting a total of 2,660 vertical feet toward the center of the earth in the process.

The four lakes are numbered in what has always seemed to me a reverse of the logical order. The true headwaters of the river are at the tiny Fourth Connecticut Lake, at the very tip of New Hampshire. When water overflows its banks, it collects just below in the Third Connecticut Lake, then the Second Connecticut Lake, then finally the First Connecticut Lake. I drove up to the Third on New Years Day of this year. It was brilliantly sunny and bitterly cold. The tops of the lakes were frozen solid and covered in a foot or so of powder. I looked west across the lake from the road, towards the small inlet where water from the Fourth must have been trickling in beneath the ice.

One day all this water would be compelled from this stillness, by something as banal as gravity, to roll and tumble over itself for hundreds of miles, over dams and under bridges, gathering in places and racing violently in others. It would be joined by the White and the Chicopee and become mighty indeed by the time it passed under I-95. Little by little, all of it would fall away, cleaving Vermont from New Hampshire before bisecting Massachusetts, then Connecticut, to empty into and become part of Long Island Sound.

I was struck, however, by the realization that the water in front of me now had nothing to do with any of that yet. It could tell me nothing of New England, or even of the Connecticut River. It didn’t know anything. It wasn’t “waiting” to go somewhere. It was just water. I felt strangely disappointed and more than a little ridiculous.

We tend to ascribe a lot of metaphysical significance to waterways. Not only do they make possible our settlements and show us the easiest paths from point to point, but there’s also something about the idea of one unbroken chain of water unifying a whole region that feels important to us. We read ourselves into places, we retrofit them with our personalities, we make something of them that they perhaps are not. This alone is what makes them places and not just geography. The Connecticut, like the Mississippi, after all, is just water, helplessly doing what gravity demands of it. We are the ones who make it anything else. I knew, just as anyone with a map might know, the path it would all take. I knew the rivers it would meet, I knew the towns that had been made possible by the very predictfability of its route. The water, obviously, could not know or care about any of this.

I was sorry to lose the feeling that I had seen these great rivers at their purest and most naked. I wanted to think that I would be able to see something elemental here, not only the germ at the core of the idea of the Connecticut River, but maybe even at the core of the idea of New England. The fact is that the Fourth Connecticut Lake will stop mattering to the fate of the river the instant the water moves down to the Third Lake. It will fall millimeters south, and then it’s not part of the lake anymore. It’s only water, and it will wander dumbly for hundreds of miles until at last it meets the ocean.

Features • Winter 2013 - Origin

In Mongolia, only the women are permitted to consume the sheep’s testicles.

In Paris, on the river Seine, a gondolier rower asks an American girl, “voulez vous m’épouser?”

“My what?” says the girl.

In Barcelona, a couple makes love atop a rock formation jutting into the sea. When a big one rolls in, splashing with force over the couple, the woman removes her hands from the man’s back and says, “Enough! Enough!”

In Shanghai, suited men on the People’s Walk offer passersby a “lady’s massage.” “You can choose the girl,” they say. “You can even see her first.”

In London, the night before the Olympics, a man in a pub trips but catches himself on the table of a beautiful woman. “Good thing I’m brilliant,” he says.

In Edinburgh, I let a room in a flat shared by Frans and Fergus. “Meet Fergus,” says Frans, holding him in the air. “Fergus is a gay cat.”

In Blue Ridge, Georgia, boys in trucks throw eggs at the cars of fags.

In Swaziland, I sleep upon the couch of the consulate’s assistant. “We do not walk unaccompanied,” she says. “Call the guard when you leave.” In Dublin, on Bloomsday, tourists wake early to walk the path of Ulysses.

In Hong Kong, I ride a yacht with my boss’s friend. In Botswana, shoeless children pet my hair. I think, “Someone, take a picture.” I think, “Who among you has a camera?” In Paris, a street performer trains his dog to hold the hat in its mouth.

In route to Switzerland, on an open-seated plane, an obese man offers his mints to the British woman squeezed between. “Are you generous to me because I see you as a human being?” she asks. “Because I sat beside you willingly?” “What?” he says, withdrawing the mints. In a hostel in Berlin, a British traveler hears me coming.”Thank God,” he says, “someone here speaks English.”

In Munich, I eat three bratwursts a day and hide liter steins in my backpack. In Johannesburg, a Zulu woman helps me navigate the city in cambis. “No,” she says when we arrive at Union Station, “no money, please.” In Edinburgh, bankers can’t breathe on the first day of July. “You could get a sun tan in this,” one says. In Mongolia, a child? tells his mother he does not want anything to eat. “Good,” she says, “we don’t have any.” In a South African housing project, above a shit-stained toilet, a sign reads: “Tswana and Xhosa only; Zulu must use downstairs.” In Blue Ridge, I play a game with old classmates. “What to do when” is the category. “There’s a black-out?” reads the card. An old friend thinks a moment, then says, “Lock him up.”

In Paris, a woman’s reading is interrupted by photography. By the fourth time somebody asks, she says, “What do I look like?” In Dublin, on Bloomsday, the football game is on and no one answers the emergency call in the lift. In Edinburgh, a stranger equally as drenched as I strikes up a conversation. He tells me he has leukemia in the manner I tell him I attend Harvard. “It’s a school in Boston,” I say, “yes, Boston in Massachusetts ... no,” I say, “no, not Boston University—another one.” In a small town in the German Alps, I find only authentic Pizzerias. In New York, a tourist is late for a show, but her suitcase

still must be opened for security. When the show releases, the man in coat check says, “It looks like somebody moved in here.” In Edinburgh, a young child amuses himself by watching his own legs walk. In London, the day before the Olympics, tourists fill the public gardens and wait for something exciting to start. In Paris, at a crosswalk, I wait between a blind man in a tailored suit and a squatter asking for change. The blind man turns to the squatter, staring instead at me, and says, “What’s your excuse?” In Edinburgh, returning home from drinks with the coworkers, I ask Frans if life ever stops feeling like a men’s locker room. “Oh, love,” he says, “locker rooms can be so nice.”

In Blue Ridge, on the floor of my childhood room, I tell myself, “I have been so many places.”

Incanting, over and again:

“I lead a life of such interest.”

Features • Winter 2013 - Origin

On October 25, 2012, The Harvard Advocate conducted an original interview with English novelist and critic Martin Amis. Amis has published numerous novels and collections of non-fiction, including *The Rachel Papers*, *Money*, and *London Fields*. His most recent book, *Lionel Asbo: State of England*, was released earlier this year. The following is a transcript of that conversation.

*

*Your recent book *Lionel Asbo: State of England* features Lionel Asbo, who is embraced and thrown into the press machine almost arbitrarily. This theme of the contemporary celebrity is some- thing that you’ve dealt with quite frequently. I’m wondering about your own celebrity status—what does it mean for you to have become such a public celebrity figure?*

It’s part of the job. If it were a profession in which you worked behind the scenes and became what you did invisibly, then that would be very nice in a way, but I have to compete for attention with millions of other sources of interest. So it’s sort of just part of the job. But some things about it are nice. It doesn’t really affect your daily life and in England there’s certainly no question of becoming like Lionel where you’re recognized and encouraged everywhere you go. The literary novel is not real fame.

*A lot of your writing is really about combating the mindlessness of the celebrity culture. What do you think then (particularly given your rela- tionship to the late Christopher Hitchens) of the corollary which is the public intellectual—do you feel like there’s a sense of obligation or a moral imperative to be able to comment on politics and talk about, you know, terrorism and the current elections? Do you think that’s a role you occupy?*

Well I suppose that for intellectual men that’s what you are—you lose the temptation and not the obligation to comment on what you see around you. He certainly liked conflict and I find I have not so much a taste for that. But I do surprise myself sometimes by having some.

*And it becomes a bit of a public furor in terms of how the press responds to these things ...*

Well it’s different in America. In England you’re not supposed to comment on these things. Your status there is more of a pact indulged. But here, where the role of the novelist is not resented, there seems to be fair comment and you’re not con- demned for sort of joining in these debates.?

*In general do you feel like you have more freedom in America? You’ve spent a lot of time in the States, because your father was lecturing at Princeton, for example, and it’s figured in a lot of your fiction. How is the author positioned differently in America, do you think?*

Well they certainly are, yes. And I think there’s a straightforward explanation for that. I think that America’s a young country that came together two and half centuries ago, and was curious to know whether it was a real country or just a col- lection of immigrants. And subconsciously un- derstood that writers would play a role in telling them what America was. In England—there’s never been any questions about what England is. It’s the country of Chaucer and Shakespeare. Its history is so much longer than that of America and all those questions have long been settled, if indeed they were ever asked.

*Your most recent novel is subtitled “A State of England.” Would you consider it in the same tradition as that of Chaucer and Shakespeare, or do you see as kind of a redefinition of what England is?*

Well it still is and always will be the country of Shakespeare. That’s its greatest distinction. But it’s certainly come a long way from then, let’s put it that way. And it’s in the process of a long decline. I don’t see any way of pretending that’s not true. And decline would take various forms, and one of them is triviality.

*I’m interested in going back to what you said about youth and the particularly the youth of America. You seem to really value innocence and freshness and fresh experience. And you’ve spoken in previous interviews about the “mental rabble of the wised-up world.” In that sense, how do you see the world in terms of its youth or innocence or its cynicism or not—do you feel that we can ever go back to that state of innocence?*

You can’t recapture lost innocence. And I don’t see any means of doing that. It would be silly to try, I think. But that doesn’t mean that one embraces pessimism. I just read Steven Pinker’s book *The Better Angels of our Nature: Why **Violence has Declined*, and it does change the picture and makes it very difficult for people who say that we are launched on a descent and, in fact, all the indicators are that the world has be- come more self-controlled, more civilized, more empathetic than it’s ever been before—despite the horrors of the first half of the twentieth century. All the indicators are down.

*To go off tangentially, from this idea of youth, you once said in an interview that every adolescent is a writer. This can be reflected in increased workshops and in creative writing programs across the country. Do you have any thoughts about the cultivation of writers? Should it be a collective activity? Should some people not become writers?*

Well, it can’t be a cooperative activity. Writing is about solitude. To be a writer you have to not only have an enormous appetite for solitude, but you have to be in some sense most alive when alone. I think that’s why, for instance, dramatic arts is probably much lower-level than fiction and poetry—because it is collaborative. I couldn’t imagine any compromise on having total say. The novelist is in a godlike relation to what he creates. He’s omnipotent, omniscient —he’s autocratic. But I think any show of interesting writing—above all, reading is one of those—can only be a good thing. And it’s interesting, in Steven Pinker’s book, one of the reasons for the decline in violence over the last several centuries is the invention of printing and the rise of the novel. And he says that the mass reading public does in fact learn to find perspective and a protective where he doesn’t much like. But that’s what fiction must to some extent do, it’s still empathy, because you’re asking the readers to see things from a different point of view.

*Related to your own literary education, what did you read when young and when you were in college?*

I read comic books until disgracefully late in my teenage years. I came to reading in my late teens. And, you know, you read and you read and every now and then you pick up a writer and you think, this writer is talking to me in a way the others aren’t. And that happened to me with Saul Bellow, most memorably, and that’s what I hope happens when younger readers pick me up. That they will think, here is someone who seems to speak to me more easily than the others. And I will want to read everything they write. And that kind of particular bond of the reader.

*You’ve been called “fiction’s angriest writer,” with parallels ranging from James Joyce to Tom Wolfe. What novelistic function do you see in this anger, as well as in the comedy that also comes up in your novels—in general, the hyperbolic language so ubiquitous in your writing?*

The word function, it doesn’t—a novel begins in a kind of dream like state. You have an idea of what it’s going to be. And then it becomes a huge sort of wrestling match to make that happen. You draw conclusions from what you’ve already written, but in the actual process you don’t think in those terms. You just say it again and again, every sentence, in your head, until it sounds right, and you do that for every paragraph and for every page. Once the idea takes, it becomes a question of craft and hard work.

*Could you talk some more about your thinking process as you begin a novel, its gestation stages, and then how you move from that to the final product?*

The key is that a novel has to begin with some strange frisson, a shiver or throb, and you think, “This is a novel I can write,” and you do need to have that. And it’s a very peculiar feeling. And then it can be sort of hardly anything. It could be derisory what this premonitory shiver gives you. Maybe just a situation, maybe just a single character. Then you start writing and see what happens. And usually you have an idea of the beginning, an idea of the end, and an idea of something that happens mid-way through. And that’s probably all you’ve got as you start. So it’s a journey without a map but with a kind of destination. And then it’s a huge exercise in trial and error and multiple decisions, multiple decisions on every page, until you get close to your kind of platonic ideal of what the novel could have been when it first struck you. But it’s an incremental process. It’s brick upon brick.

*To what you extent do you find that autobiographical elements play into this process of crafting a novel? To what extent is an autobiographical element, for example, part of that initial shiver?*

Some novelists do go quite close to life, Philip Roth as well as Saul Bellow. But if you put a real character in a novel they will look very strange, out of place. What you have to do is change the person so that they fit the novel. I put Christopher Hitchens in a novel, my last one, and he went in quite easily, but I had to give him a toss a few times, I had to change what had to be changed. But that was quite rare for me. I think little segments of your life, you consult—you come to a character and you say, “Who is this like?” You fixate on someone you have known, maybe not at all well, for how they look, and someone else for how they talk, and you cannibalize your acquaintances and friends and people you just pass on the street, and you cobble them together that way. But it can be a help to have a real-life model, although I wouldn’t—the thing about fiction is freedom, and a real person will make demands of you that aren’t really right for fiction where you’ve got to be free.

*In terms of fiction and the novel in contemporary culture, do you have any thoughts on what now is the place of the novel? Do you think it could play a different role than it has in the past? And where could it be going? What new direc- tions could the novel be taking?*

Well, I wouldn’t know about them because I don’t read my youngers. And the only contemporaries I read are pretty much my friends. Because to read the latest book by the 25-year-old sensation seems to me a very uneconomical way of using your time. I would say that the novel has responded to modernity, to the most recent stretch of modernity, by becoming much more streamlined and dynamic. Because the pace of history seems to speed up and seems just as important to us, whether or not it actually has. And things are moving too fast now for the kind of long essays, the meditative novel that was popular couple of generations ago. Life is too fast for that now and novelists, being modern people, have resorted to that. I imagine the novel wil go on getting streamlined. The arrow of propulsion will get sharper.

*Speaking of the arrow of propulsion, do you feel like you’re getting sharper and sharper?*

It’s a tradeoff. Your musical abilities get more limited by your craft gets better and you know what goes where. You can modulate and you can ... this concept of earning what you write becomes clearer to you: you can’t just put the words on the page without going through a process that involves pleasure and also some pain. And you have to write it, you can’t just state it. So the technical side gets easier. The inspirational side gets more difficult.

*You did say once in an interview about your father, that there’s a fear that older writers can have of younger writers, a fear that the younger writers might have a better sense of the contemporary –*

Well, yes, I think that’s inevitable and maybe as a result you will set your stuff in the recent past. It would be very undignified to try to keep up with the new. You have to let it go at a certain point and say, I do what I do, and I’m not going to just go and find out what everyone’s up to, stick to your own milieu, your own area.

*We’ve talked about young writers and older writers. You wrote some of your first novels when you were in your 20s—how would you contrast your first novels to what you’re doing now?*

Well I can’t read my early stuff ... I mean, I can see it’s lively and all that, it’s surprising but technically it’s embarrassing. The novels of mine that I like most are the most recent ones.

*Over the past few years you’ve talked a lot about growing old, about mortality, and about the distastefulness in that. And yet more recently, after the death of your dear friend Christopher Hitchens, you’ve spoken more about the gift of life. How would you say your philosophy on life has evolved over the past few years?*

Well, as I said when you arrive, when you start communing with yourself in your teenage years, you start to keep notes and diaries and become self-aware, and the world looks like a—you’re saying hello to the world. And then after a certain point in your life you find that you’re beginning to say goodbye. And that has a certain kind of poignancy and things do look precious when you’re absolutely sure that you’re not going to be around for that much longer. They say that age gives nothing back ... but I think it does.

Features • Winter 2013 - Origin

Sometimes, when the weather is mild, I move my writing life outside, to an old cane chair under the boughs of an apple tree that was old before I was born. Not far away, but unaware of me, a muskrat browses in the grasses by the brook. Red-winged blackbirds swoop across the water and a goldfinch, like a drop of distilled sunshine, darts through the glossy branches of an ilex.

The muskrat, the birds and the holly tree are natives here. I am not. Only my dog, a liver-and-tan Kelpie, is a fellow exotic. Ten years ago, I plucked him from a sheep paddock in rural Australia and set him down in another hemisphere. He is insouciant about this, as befits his hardy kind.

So while his warm flanks twitch in a doggie doze, it falls to me to reflect on what it means to live so far from our place of origin, so far, indeed, that the cold winds of a Sydney July have been replaced by the soft and buttery summer air of Martha’s Vineyard. I cannot explain to my Kelpie that the Indo-European root of the word “home” is “haunt.” Nor can I explain to him how and why it is that I am haunted by absence and distance, by dissonance and difference, even if the alien corn that we will eat for dinner tonight is a sweeter variety than the starchy cobs of my Aussie childhood.

Nothing is as sweet in the end as country and parents, ever.

Even if, far away, you live in a fertile place.

Odysseus said that. Or rather, Homer did. I know next to nothing about Homer—who he was, how he lived—yet I feel he knows my heart. Separated by three thousand years, by gender and culture and geographic space, this ancient shadow is able to put words to the feelings that I have on a sunny day on a little island, as I think of the larger island that is my native home—that sits, like Ithaca, “low and away, the farthest out to sea,” where the ribs of warm sandstone push up through thin, eucalyptus-scented soils.

Home. Haunt. I sit in my garden and look across to the house I have now: a house the first beams of which were cut and shaped a century before the white history of Australia even began. When I run my hand over that rough-textured oak, I imagine the hand that planed it—the hand of a grist miller, himself an exotic transplant, the second or third in a line of English settlers who had come to this place drawn by the power of rushing water.

If any home is haunted, this one should be. In 1665, the very first miller, Benjamin Church, bought the land from the native people of the place, the Wampanoag. He dammed the wild brook they called the Tiasquam, and set his grindstones turning. In so doing, he destroyed the herring run that had fed the Wampanoag each spring, when the fish known as “the silver of the ocean” poured upstream to spawn.

Benjamin Church dammed the brook.

It is just one sentence in a long story. The story of human alteration to the natural world. It happened on the Tiasquam brook in Martha’s Vineyard, as it happened in uncountable places. As it happens now, in the Amazon, in Africa, in Western Australia, Tasmania, the Alaskan Arctic and innumerable corners of the world. A choice, a change, and the planet that is our only home reels and buckles under the accumulated strain.

Often, this story has also compassed stories of dispossession, in which the needs of the newcomers and their industry disrupted the imperatives of the native people. As Benjamin Church built his mill in 1665, an English neighbor fenced pasture for his imported livestock, and the Wampanoag were no longer free to hunt the deer and waterfowl that sustained them. Another settler set his hard-hoofed beasts loose to trample the clam beds, and a band of Wampanoag went hungry that night.

War followed, as war always has followed such acts of dispossession. In 1675, the Wampanoag on the mainland rose up against the English colonists. Benjamin Church, grist miller no longer, became a captain in the English army.

His principal foe was the Wampanoag leader, Metacom. For six months, Metacom had the English on the run, destroying a dozen settlements. The colonial enterprise in New England teetered. It was Church, the former miller, who devised a way to turn the tide of battle. He enlisted Indians at odds with Metacom to teach the English their guerrilla tactics. On a humid summer day in 1676, Church led the force that trapped Metacom and shot him dead. He regarded Metacom’s dead body and declared him “a doleful, great, naked, dirty beast.” He ordered the corpse drawn and quartered and had the quarters hung from four trees. Church kept the head, which he sold in Plymouth, at a day of Thanksgiving, for thirty shillings. It was placed on a tall pole to overlook the feast.

Everyone knows the story of the first Plymouth Thanksgiving in 1621. Metacom’s father, Massasoit, attended that one, offering help and friendship to the hapless, half-starved English Puritans. Few know the story of the Plymouth Thanksgiving of 1676, presided over by Massasoit’s son’s decapitated, rotting head. We like that earlier story much better. Let’s not do black armband history. Pass the turkey. Let’s we forget.

But I can’t forget. Though Benjamin Church’s mill was torn down, this land bears his imprint. The Tiasquam brook remains dammed, the herring absent. And the grindstone is still here, set as a doorstep at the entrance to my house. Five feet in diameter, a foot and a half thick. When my foot lands on its notched ridges, words from Gerard Manley Hopkins’s poem echo in my head:

*Generations have trod, have trod, have trod;

And all is seared with trade; bleared, smeared with toil;

And wears man’s smudge and shares man’s smell ... *

* *Benjamin Church’s mill was built a hundred years before the Industrial Revolution that dismayed Hopkins. But it industrialized this landscape. And now I live where he lived, in an American home on Indian land, haunted by ghosts who lived and died unaware that my land, my homeplace, even existed.

I did not mean to become part of this story, to know, so intimately, all this history so very far removed, and yet so sadly similar to my own. Metacom has much in common, after all, with Pemulwuy in Sydney or Yagan in Perth, guerrilla resisters whose heads also ended up on display—Pemulwuy’s pickled in spirits and Yagan’s shrunken and smoked. But that’s black armband history, too, and, as a schoolgirl in 1960s Sydney, I did not learn it. In those days, I could not have told you that the home I lived in stood upon Eora land. I learned these things not in school, but later, as a newspaper reporter, covering Aboriginal land rights battles and the efflorescence of indigenous art. I was, in a way, a foreign correspondent, venturing into an alien culture without even leaving my own shore. That reporting led on to a job as an actual foreign correspondent, and so I became an accidental exile. I meant to leave Australia for just a year. But way leads on to way. Like Odysseus, I went to war—although as a writer, not a warrior—and then found my homeward journey diverted by quests and siren songs. What was to have been my brief foreign fling has become, by unplanned stages, my life.

In dictionaries, definitions of home are various. It is both “a place of origin, a starting position” and “a goal or destination.” It may also be “an environment offering security and happiness” or “the place where something is discovered, founded, developed or promoted. A source.” My “place of origin” was an ordinary Australian suburban childhood of the sixties, and though it led to a “destination” elsewhere, it was the place of discovery and a source of conviction about our responsibility to our only home, this fragile and beleaguered planet.

I have said that I live now on the banks of a little river that was dammed in 1665. When I first left Australia in 1982, a greater river, a larger dam, was very much on my mind. That river was the Franklin, in southwest Tasmania. A river wild from source to mouth, already a precious rarity in the smeared, bleared post-industrial world. Yet a river whose wildness was in clear and present danger. Works were already proceeding for a dam that would flood a pristine wilderness to yield just 180 megawatts of power.

I had started covering the Franklin controversy as a journalist in 1980. In February of 1981 I rafted part of its length, on assignment for my newspaper. It was, at the time, the hardest and scariest thing I had ever done. I was not what you would call an outdoorsy type. To paraphrase Woody Allen: I was at two with nature. Until I started covering environmental issues, I’d never gone bushwalking or slept one night in a tent, much less steered my own small rubber raft over heaving white water. That first night on the river, having carried gear all day up and down a sheer, slippery, rain-lashed mountainside, I lay wet, aching and apprehensive, wondering what mad ambition had led me to sign up for this. But that Franklin trip changed me, profoundly. As I believe wilderness experience changes everyone. Because it puts us in our place. The human place, which our species inhabited for most of its evolutionary life. The place that shaped our psyches and made us who we are. The place where nature is big, and we are small. We have reversed this ratio only in the last couple of hundred years. An evolutionary nanosecond. The pace of our headlong rush from a wilderness existence through an agrarian life to urbanization is staggering and exponential. In the USA, in just two hundred years, the percentage of people living in cities has jumped from less than four per cent to eighty per cent. By 2008, half the world’s population was living in cities. Every week, a million more individuals move to join them. The bodies and the minds we inhabit were designed for a very different world from the one we now occupy. As far as we know, no organism has ever been part of such an experiment in evolutionary biology as we as a species are now undertaking— adapted for one life yet living another. We are, in a way, already space travelers. We have left our place of origin behind and ventured into an alien world. And we don’t yet know what effects this sudden hurtle into strangeness will ultimately have on the human body, the human psyche.

*(This piece was adapted from Geraldine Brooks’s 2011 Boyer Lectures, presented by the Australian Broadcasting Commission.)*

Poetry • Winter 2013 - Origin

Sanctuary, I am light within

your innermost organ: whitened

is the heart you assign to me,

and I assume its shape with ease.

Breath comes to one from another,

for soul is this remnant of expulsion

shriveled on body’s outskirts until

elongating it rears up: guest ready

to love like only the shapeless

can. This air is everywhere.

These faces shape themselves

from light swallowed by water.

I feel river in my under-skull,

tissue rinsed by currents eddying

around nerves. Turn your eyes,

apparitions stream from them.

*

Generations of me rush to the shores

where, touched, your loss sinks below

lines of bodies falling, strapped,

feet tied in bunches, where the hurling

sounds reach me here, where safety

has gained remeaning unentirely.

I do not know these sounds

or their origin, only that my life

has spent itself searching

for black clouds thick

under skin, explosions boiling sky,

poisons mixed like wild colors

of sunset, intoxicating freedom:

I am running, and when I hit

the confines of white-blinded

skull, I make these sounds.

*

There are no sounds these bodies make,

there is the great flush cleansing

their eyes and sterilizing their pink

mouths, there are rocks buried that

no one saw: these are the currencies

of river’s gamblings, the game

water plays with the sun: let us trade

blindness for mineral abrasion,

let us guess at the formulas this world

reactively rearranged: numbers, bonds

flowing like lips between rage

and desire. We can unite, I will pour

myself on top of you, river, and you

will suffocate under ignition.

*

I would not trade myself for anything.

Time, your inflation was the mistake:

you submitted to the forceful massage,

now you swell at speeds that distort

my explanation. I am your container,

I nourish you, and I will turn away

in times of anguish. Do not desire me—

desire is your premonition of loss.

Speed from me, child: I am the river

as light unarches.

Poetry • Winter 2013 - Origin

It is the nature of this game to want possession

then to want to give it up

to get it back so you can give it up again.

Nobody stops to ponder the ball, the way John Keats

pondered a cue ball’s “roundness,

smoothness, volubility”: its joy in being hit.

Imagine the score is tied, and I take the ball away

In order to sketch it, or incorporate it

Into some kind of quasi-tribal dance routine...

I thought we had agreed to play. I thought you said

We’d play and play all day, beating and being beaten,

Taking turns at losing, learning its advantages

for a young man’s character, then changing fates.

What kind of game is this, your going away forever,

sending word, years later, that you’d died?

Poetry • Winter 2013 - Origin

I sing of arms and the man whom fate had sent

To exile from the shores of Troy to be

The first to come to Lavinium and the coasts

Of Italy, and who, because of Juno’s

Savage implacable rage, was battered by storms

At sea, and from the heavens above, and also

Tempests of war, until at last he might

Build there his city and bring his gods to Latium,

From which would come the Alban Fathers and

The lofty walls of Rome. Muse, tell me

The cause why Juno the queen of heaven was so

Aggrieved by what offence against her power,

To send this virtuous faithful hero out

To perform so many labors, confront such dangers?

Can anger like this be, in immortal hearts?

There was an ancient city known as Carthage

(Settled by men from Tyre), across the sea

And opposite to Italy and the mouth

Of the Tiber river; very rich, and fierce,

Experienced in warfare. Juno, they say,

Loved Carthage more than any other place

In the whole wide world, more even than Samos.

Here’s where she kept her chariot and her armor.

It was her fierce desire, if fate permitted, that

Carthage should be chief city of the world.

But she had heard that there would come a people,

Engendered of Trojan blood, who would some day

Throw down the Tyrian citadel, a people

Proud in warfare, rulers of many realms,

Destined to bring down Libya. Thus it was

That the Parcae’s turning wheel foretold the story.

Fearful of this and remembering the old

War she had waged at Troy for her dear Greeks,

And remembering too her sorrow and her rage

Because of Paris’s insult to her beauty,

Remembering her hatred of his people,

And the honors paid to ravished Ganymede –

For all these causes her purpose was to keep

The Trojan remnant who’d survived the Greeks

And pitiless Achilles far from Latium,

On turbulent waters wandering, year after year,

Driven by fates across the many seas.

So formidable the task of founding Rome.

News • Winter 2013 - Origin

In Werner Herzog’s wild film *Aguirre: The Wrath of God*, which we recently screened upstairs in the Advocate, the main man Aguirre goes mad in pursuit of the fabled city of gold, El Dorado. He co-opts a royal expedition on the Amazon and presses madly on down the river, drunk on pride and the scent of immortality.

One scene brings a pair of natives to the raft; they have come to tell about a prophesy. But Aguirre sees a gold necklace on one of them, and loses his composure. *Where did you get that?* he growls with crazy eyes, Klaus Kinski eyes. *Where does this gold come from?*

Aguirre’s madness is to go on downstream when there is nothing there but death. His madness is the promise of the origin, the mirage of a city that rises up out of a necklace. He assumes there has to be a single source. On and on downstream, the raft of Aguirre. *I am the wrath of God*, the crippled Spaniard bellows at the silence. *Who else is with me?*

*

image courtesy of www.macguffinpodcast.com*

Herzog’s camera swings in a dizzying circle. The jungle does not move—only the raft does, and the camera. Aguirre himself is finally still. The only movement on the raft is the monkeys.

The filming of *Aguirre* was its own ordeal—think a German New Wave *Apocalypse Now*. But where Aguirre the madman fantasized of arriving at the source, Herzog’s own imaginative expedition took him only as far as the river. Both these men were megalomaniacs, in their way, but we think warmly about one of them.

A number of great rivers and shores mark this issue of the *Harvard Advocate*. Some are imagined, some are quite literal. Through the theme of *Origin*, we wanted to indulge an age-old fascination with the times and the places of beginning. It was important to us that the word not be pluralized. It would be *Origin*, not *Origins*, so that each contribution had to face the same but separate challenge: the inherited structure of a singular yearning. Each text, that is—however compliant or disruptive—would be thought of as its own expedition.

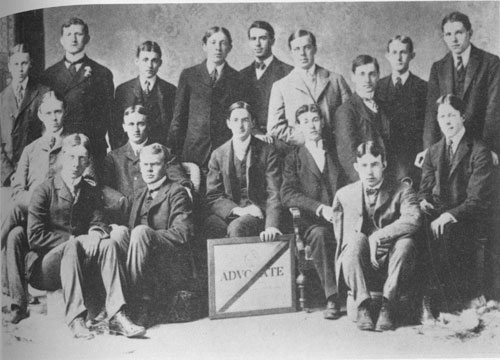

The theme is fitting in a year where we have made bold strides forward as an organization—into the digital landscape, through our new blog and updated social media presence, and also into our history, thanks to our exciting collaboration with the [metaLAB@Harvard](http://metalab.harvard.edu/about/) and the University Archives. It has been our aim to move past the nostalgic languor of being “historical” and to start animating our history in illuminating ways. For our blog’s weekly column, members have been digging through the archives—leafing through messy piles of bound volumes in the Sanctum—and a variety of gems have come to light: the early work of [Wallace Stevens](http://theadvocateblog.net/2012/11/21/from-the-archives-wallace-stevens/), as expected, but also a scandalous excerpt from [Henry Miller](http://theadvocateblog.net/2013/02/06/from-the-archives-henry-miller/), some fascinating advertisements, and a number of poems submitted by one [Lou (here “Louis”) Reed](http://theadvocateblog.net/2012/11/13/from-the-archives-the-velvet-undergrounds-lou-reed/).

*image courtesy of www.bookofjade.com*

The cooperative process of creating and developing *Notes from 21 South Street* has allowed us to expand the Advocate’s presence beyond our four static issues per year. We have endeavored to share online something of the wonder we find within the four walls of the Advocate house: a wonder based as much on collision as it is on intention—those chance meetings, collaborations, and discoveries of new ideas that take place outside the boards’ official mandates. The *Advocate* this year has been inspired not only by its young and energetic membership but also by the new connections we’ve forged outside the magazine, from our new allies in the digital sphere to the friends we made at our open-to-all January writers’ workshop. To all of these, our heartfelt thanks.

We hope that you enjoy the *Origin* supplements on the blog and see them, along with the rest of the work published there, as an effort to share the bustling life of the building with our readers. The historical supplement, which will be released this coming week, was designed with similar intentions.

At 21 South Street, surrounded by traces from some of America’s greatest writers, it is easy enough to think—with Umberto Eco (or with the Kinks)—that all the stories have already been told. By getting our past off the shelves and into our hands, however, we seek to make our history available for play and variation. Nostalgia has the power to lure us, like Herzog’s Aguirre, towards a false authenticity, and to leave us lethargic thereby. In the production of the *Origin* issue, our interest has been rather in the expedition itself, because it is there that we see the realest work of imagination.

Andreas Huyssen writes that remembrance, too, is a pole of utopia. With this in mind, we offer you *Origin*. After *Blueprint*, after *Fanfare*, I like to think of this issue as the long walk back after a night out—towards home, perhaps, or to wherever you end up.

*By Alexander Wells '13, President Emeritus*

*You can view this blog post and more at the Harvard Advocate's blog, [Notes from 21 South Street](http://www.theadvocateblog.net).*

Fiction • Winter 2013 - Origin

Though Katherine wanted to be a woman, wanted to butterfly out bright and kaleidoscopic onto the streets fully formed, complex and multitudinous, she found herself, upon each insistent inspection of her body, solidly still a girl. She blamed her mother, a girl’s mother, a sad mother, a mother who will remain for the rest of her life postpartum. She blamed her body, a girl’s body, and her clothes, still and girlish in her closet. In the formless dresses and little blouses she saw herself, the small tender swell of her breasts, the smooth slender fall of her hips into her thighs, an unblemished line, a child’s thin lips, a child’s thin arms, the girlish curls that unfurled blonde and bouncing from her forehead, and the odd dark tuft of hair a few inches below her navel, out of place and offering futile promises of nubility. She blamed her love, a girl’s romance planned in passed notes and notebook graffiti hearts, a romance that at fourteen had felt safe, and now, at fifteen, felt safer.

And even though her house predated her by some years, Katherine still considered her home a girl’s home. The house sat alone atop a hill, covered on one side by a small forest of dark fir trees. A winding grey scar divided the forest in two, a gravel road connecting the house to a private beach. Isolated above the forest, smoke puffing out of the cobbled chimney, the breeze carrying salt from the ocean, it was less a house than a story, a girl’s fairy tale into which some strange hand had written her.

Even before she turned fifteen, the desire to leave grew in her. She began walking, reaching places only to find them immediately foreign and strange. Her boyfriend’s home no longer held anything for her except unwanted security and uncomfortable promises. It was a place where parents discussed weddings behind closed doors and tiny lovers discovered their tiny bodies with increasing boredom and respect behind their own doors. As she lay in his bed, her boyfriend’s head on her near nonexistent breasts, she would take his hands in her own, pull strands of her hair from the band of his watch. She would look at both pairs of hands, folded neatly together, and think, these are not the hands I want to spend the rest of my life with, neither his, nor mine.

She became a girl always in transit, moving between people and friends with an abandon that confused and frightened her. She longed for some ineffable stability, dreaming hard and solid dreams, dreams of bodies and muscles and empty houses and cars driven by strong, unfamiliar hands. She dreamt of her father. Every day he drove her to school and every evening he picked her up, letting her out of the car and into the house, and she would go into the kitchen and peek out through the blinds and watch her father sit alone in the car and long for a place of her own, wondering why those moments of silent familial voyeurism seemed to her the most beautiful in the world.

At fifteen and a half her father took her to get her driver’s permit at the DMV two towns over, and when she passed the test he brought her home to find a present in the driveway, an old orange Volkswagen bus.

Feel free to leave, he told her, and smiled. Just don’t get caught.

She drove to the beach, stopping only because she could go no further. Through the windshield the sea stretched out before her. She felt the uncomfortable settling of her eyes on the horizon, the sheer size of the distant line, like thin twine that tied the world together. Dirt and small cracks in the glass speckled and tinted the ocean like a dying television set. The waves rolled thick and vicious in the edgeless distance. She pressed her hands to the worn glass. She kept her hands there. She looked at the waves and when they did not crash over her, she stepped out of the car.

On the beach she and the Volkswagen bus stood alone. She leaned her hand on the side of the door and removed her shoes and socks, placing them next to the wheel, already submerged in sand and dust and rusting from the salty air. She curled her toes against the earth, squeezing the small fragments in the soft empty spaces of her feet, feeling the sand trickling between her toes.

She left the bus and walked towards the break. Tiny footprints followed her down towards the water. Little fossils in the sand. How small they were, pressed too shallow to possibly be her steps, to possibly have borne her weight.

Water brushed her toes. She stepped further into the ocean, submerging herself in increments, her toes, the balls of her feet, her heels, her ankles, her slender shins. The tide held her, rushing forward to embrace her and sliding back into the sea, pulling with it the loose pebbles around and under her feet. She thought about the earth bleeding away beneath her. Salt and quartz rubbed raw from underwater rocks, crushed sea shells and mollusks, decayed algae, odd bits of life ground into dust. How easy it would be to go with them, for the ocean to hold on to her feet and pull them clean from her ankles away into the sea. How easy to rip her into little pieces, joint by tiny joint rubbed away in the waves leaving only even tinier bits behind, particles of a shell joining the others broken in the sand.

How odd, she thought, to stand there, whole, and be anything at all.

The sun set. Violent reds and remote violets streaked across the darkening day. Screeching gulls became bugs swarming in the warm air. She checked her phone. Her boyfriend had called four times, her mother not at all.

At the beach in the bed of the old Volkswagen she lay down and cried and imagined herself to be her mother in bed, immobile, and infinitely far away, an adult and, like her daughter, still a little girl.

She began going to the beach every day, coasting the old Volkswagen down the hill and through the forest until she hit the sand and the bus slowed to a stop. Alone on the beach Katherine forgot herself. Every night she would undress and lie in the sand and let the surf play over her bare body, feel its cold fingers find her most intimate places. She lay there until she lost feeling in her toes and knuckles, until her skin darkened and her joints froze stiff. Then, she would rise and dress and return to her car and fall asleep, holding herself in her arms and wondering whom she was becoming.

One day she found something strange. The beach lay quiet and the surf bobbed in and out, leaving little gifts for Katherine just past the edge of the water. She picked them up and held them, bits of shell and rock and broken bottles saved from a future of sand. Walking along the swash, she saw something in the distance, a dark lump peeking out of the sand. She approached it and stopped and kept going, looking at the pinkish thing in front of her, a pinkish thing that had no place lying there on her beach, and certainly no business lying there alone. She stood over it and poked with a piece of driftwood, turning it over and over until she finally had to admit that yes, there on her beach lay a human foot.

The foot was big. A men’s size twelve, she would have guessed. Pale blonde hair covered the top of the foot and little curly tufts puffed off the knuckles of its toes. The heel was square, its nails well manicured, cut short, and the skin looked soft and smooth despite the foot’s time in the ocean. The foot ended just above the ankle, cut clean across, and a small nub of white bone poked out of the top. She turned around, looking for some sign of the foot’s origin, a corpse or a scream, or even another foot, but the beach lay empty. She lifted her own foot, hesitated, and touched the foot with her toe. It was still warm. Behind the skin the meat of the foot pulsed red and wet, the fresh flesh almost oozing, veins almost pumping out thick rich blood so that the foot appeared alive and Katherine nearly expected it to right itself and hop away down the beach.

She went home early that night and ate dinner with her parents for the first time in several weeks. As she stared down at her meal, a cut of pork loin, thick, pink, and juicy, which her dad had prepared just for her, she could not help but remember the foot. She could not help but see its supple flesh on her plate, the hunk of meat narrowing and elongating before her, dividing into five little toes that curled around her unused fork, begging her to pierce the fleshy ball of meat under its heel.

She excused herself and went to bed without eating, leaving her parents confused at the table. Upstairs in bed, Katherine called her boyfriend for the first time in three days.

How are you? he asked.

She hung up the phone.

He would not know how to handle the foot on the beach. He would tell her parents. He would call the police. He would comfort her and tell her to forget the foot and to leave the beach. He would not understand it was her beach, and by extension, her foot. A sudden desire seized her, an uncontrollable urge to break open his chest and see with her own eyes what filled him. Did there exist within him worries beyond their two hands, or theoccasional togetherness of their lips? Or would she find simple flesh and blood?

The next day she skipped school and returned to the beach. She worried about the foot and hoped it had

disappeared, but, at the same time, Katherine was happy to have something to worry about other than herself.

But this time the foot was not alone. More body parts had washed ashore and joined the foot on the beach, all

clustered together as if huddling for warmth, as if they had found each other after a long lonely voyage. A nose

caught her attention first, long and thin and pinched at the bridge, pointy with wide nostrils and tiny curly hairs

that stuck wiry out of the holes. The thin hairs blew gently in the sea breeze, so that it seemed as if the little

discorporate nose still breathed, pushing oxygen to some unseen body. An arm lay next to it, darker in color than

either the nose or the foot, speckled with brown freckles, coarse hair, but clearly feminine, slender lilting wrists,

tapered forearms. She saw a chest too, a man’s chest, wide and bright, light skin and hard dark nipples, well

defined abs cutting the stomach into compact sections of muscle. They all lay there splayed before her, spectral

and carnal, missing pieces from missing wholes.

The sea bit her eyes and stung her cheeks. The water washed over her feet, still attached solidly to her ankles. She felt her chest and her arms and her legs, all connected together. The wind swung her hair in a lilting waltz and it fell over her eyes, covering her world in curly yellow lines. But when her hands swept the strands from her face the body parts still lay there in the sand, the still pieces of men.

More body parts washed onto the shore, and more the day after that. Each day Katherine returned to the beach and watched the legs and the torsos and the ears and ankles float onto the sand and join the growing pile of limbs and flesh. She told no one, and saw her family less and less. Her father thought she was going to her boyfriend’s house, her boyfriend thought she was taking care of her mother, her mother thought Katherine had finally become like her and given up. Katherine kept up appearances, going to school, kissing her boyfriend, kissing her father, telling her mother they were both fine, her mother telling her they were not.

Every day she returned to the beach and watched the pile of loose body parts grow. By the end of the week they had filled the beach, eyes and the eyelids, buttocks and knuckles and knees and ankles strewn across the sand, thousands of limbs piled high and wide, more floating onto the shore every hour. Infinite combinations of bodies, infinite combinations of people.

She began to build. It started with a thigh, thick and muscular, strong smooth quad rising up behind the skin, which was peach and soft, covered in a soft apricot fuzz. She held the thigh in her hands, surprised by its weight, by its density, how it filled and completed the open palm of her hands. She set the thigh down away from the pile of body parts, and saw the small ghostly marks of her fingers, clawing white lines on the pink skin.

She chose an arm next, and then a chest, and a pair of feet and large old eyes, and knees, long dextrous fingers, thick muscled fingers with hair on the knuckles, cheeks and lips with small wrinkles around and below the mouth, unexpected attractive grooves that held her and held her, changed an arm, picked a forehead, switched the feet, now larger and clumsier, chose hair long and wild and dirty, chose a stomach, beautiful with a long rippled scar, creased knotted skin that stretched across and through its navel, which was round and shallow, picked ears, chose new ears, building and building, picking and choosing the pieces, feeling and finding more intimate places, firm buttocks, a groin, places she had felt before in the dark, but never seen, both she and her boyfriend ashamed of their small developing bodies, but in this body developing before her she felt no shame, in this body she saw only the potential of perfection, the potential of one beautiful solid body among infinite imperfect ones, the potential of a body of her own so completely not her own body, a body alluring and whole and frightening, the body of a man, sturdy and worn, wearing the signs of life, scars, wrinkles around the eyes, changed a leg again, longer, taller, stretching out and beyond her, out and beyond her busy building hands.

When she finished she realized he was older than she had expected, probably over twice her age. She took off her clothes and lay down next to him naked in the surf like she used to do at night when she was alone, and she looked at their two bodies together. She placed her feet next to his and stretched herself alongside him, feeling the curve of his thigh, the muscle of his back, the empty spots between his wide ribs, and his shoulders and neck and head, which stretched past her own head, perhaps a foot longer or more. They lay there together for some time, growing cold together in the swelling ocean, the sand and surf playing up and down their frames. She sighed and placed a hand on his chest. Its warmth surprised her, as well as the small rhythmic movement of his breast, probably caused by the pulse of the waves. She pressed her hand down hard and gripped his chest, holding as much as she could with her small hand, until another hand closed softly down on hers.

Her breath stopped. Her heart stopped. The whole of her body froze in that moment, the collapse of hand onto hand, the twining of fingers, the shared pulse of two separate hearts meeting in their palms. He stood, unfolding himself into the twilight, his long solid body taking up more space than she believed possible. For the first time Katherine became aware of their nakedness, the shame of exposure and the strange intimacy of their bare bodies together. She took him in, for the first time, as a whole, not the sum of chosen parts, but a body and a being separate from her own. She looked at his groin and covered her breasts.

I need to go, she said, and he nodded at her.

Then go.

His voice, impossible and loud, stretched out into the night like a deep siren, a primal pulse that hit her hard in her exposed chest. She did not expect that voice, that rich old hungry voice, that penetrating voice that struck deep into her heart and the back of her knees.

Then go, he had said, and she wanted to go. She wanted her home. She wanted her mother and her father and even her boyfriend. She wanted familiar arms to embrace her, not these great trunks, hard muscular arms that split from this man like tree branches, arms that could crush her small girlish body into its tiniest parts. He touched her hand and held it and pulled it away from her chest and she didn’t move. He touched her other hand and held it and pulled it away from her chest. They stood there like that as the sun fell behind the horizon until she could no longer see him, he holding her hands in front of her, like a guide pulling her forth into the night.

She stayed away from the beach for a few days, working herself back into the life she had started to leave behind. She ate at home, saw her boyfriend, expressed worry about her mother, frowned in the mirror. But even alone, just behind each action stood the man she had built on the beach. She saw him in flashes at school, caught his eyes in mirrors, saw his arms in crowds, heard his voice in the murmurs of students and shopkeepers. Then go, she heard him say over and over, his voice made wide and infinite in memory. Go, she thought, then go. On the night of her sixteenth birthday she returned to the beach, the large pile of body parts looming in the distance as the bus pulled up onto the sand. There he stood, bare and beautiful. He faced the open ocean, which lapped hungrily at his feet, as if desiring to pull him back into the sea and reclaim his beautiful body as its own. She walked down the beach and stood next to him, and he smiled at her with old knowing lips, and they said nothing to each other for some time.

Aren’t you cold? she asked him.

No. Are you?

No.

He held out his hand and she took it and they watched the ocean together, the waves beating and pulsing with their own hearts. The sun set. The earth darkened.

I should go, she said.

Then go, he said. And she did.

She came back every day to be with him, finding it more difficult to return home each night. They walked together along the beach, sometimes holding hands, sometimes not, sometimes talking, often silent. When they talked they rarely spoke in conversation. Rather, they took turns listening to each other. She told him about her fears and worries, about her mother and her boyfriend and her body. She asked about him, but he only told her about other things. He spoke of love and desire, of the sea and the waves, of bodies and sex and fear and yearning and hope and hopelessness. There on that beach she wondered if it were possible to speak in anything less than grand statements and fantastic truths. She wondered if there was anything that he could not explain to her with fullness and beauty.

She begins skipping school. She begins forgetting her other world, and imagines that it forgets her. Every morning she drives to the beach, each night she drives home later and later. When she arrives, he undresses her, exposing her soft body to the day. He looks at her, and she at him. With her boyfriend she always dressed quickly when they finished, turning her back as she slips on her shirt, putting on her underwear under hisblankets. The man on the beach takes her in his hands, traces the lines of her body, guiding her down his chest, learning her body, the sensitive hidden spots, the inner lip of her thigh, the back of her neck, the curl of her ears, the soft spot between her navel and her groin, and the lines below that, delicate and swollen and tender and new. Her hands discover the body they built, lingering on his chest, the soft skin just below the knot of pelvic bone, moving to envelop his body with her own, possessing him with her flesh, learning for the first time the rapture of bodies.

She keeps skipping school. Her teachers call but her mother doesn’t answer and her father stays late at work. Her boyfriend calls her and she ignores him. Over time her phone rings less and less frequently, and the time between calls weighs on her, though she never answers. Why aren’t they calling? She throws her phone into the sea. On her small arms and small legs and small breasts she feels the shame that drove her to the beach, the shame she must relearn every time she enters her bus and drives home. She tells this to the man on the beach, gushing her envy of his body.

Don’t you understand? she asks him.

She takes his chest in her arms, which barely stretch around his chest, and presses her cheeks into his flesh.

I want to be like you.

He looks at her, and speaks slowly, flexing the upper palate of his mouth, his tongue, stretching the muscles in his lips.

Then change, he says, If you want, you can change yourself.

So she does. She hunts through the old forgotten pile of body parts lying on the beach, tearing through thin legs and wide wrists, still fresh and warm, the pile moist with sweat, choosing the future pieces of herself. Small things at first, a long pair of eyelashes, slender blue fingernails, trading away the hidden corners of her body. As she extricates herself from the pile of limbs she is surprised at which arm is hers. She turns around and the man watches her, carefully inspecting her body.

How do I look? she asks him.

She returns home, testing the changes in the shine of the faucet, her face in the downstairs windows. Behind her transparent nose and eyes she sees her father pull up outside their house. She watches him from behind the blinds and for a moment feels like her old self, loves her boyfriend, loves her mother, upstairs crying, loves her life which she knows just needs more time, just needs a little more time. Her father gets out of the car and walks towards the house and suddenly she knows. She knows that her father will take one look at her and see it all, see the strangeness in her, or worse he won’t even recognize her, he’ll scream at her and ask, where is my daughter, who are you, where is my daughter? The door opens and closes, revealing her father, standing there looking at her. Her heart tightens.

Oh, hi honey, nice to see you. He hangs his jacket on the coat rack by the door. What are you doing here? he asks, Shouldn’t you be out?

I’m just back for a second, dad.

He smiles at her.

Well, have fun dear. Be safe.

I’m going to go check on mom, she says.

Okay, now.

Her father walks into the living room and sits down to read. She walks up the stairs and knocks on the door, which hangs ajar and swings open. Katherine stares at her mother who lays still on her side and doesn’t move despite the creak of the hinges or feet stepping across the floor. She can hear her mother breathing. Whether she is awake or simply crying in her sleep, Katherine can’t tell. She turns to leave, and just as she reaches the door she hears something.

I understand, says her mother, why you’re never here. I’m not angry. If I were you, I would have left too. Back in her bus, Katherine curls up in the back seat to sleep. Time passes and the sun crests the hill, providing just enough light to see by as she coasts the bus back down the hill to the beach, where her man stands waiting, watching the unending ocean.

Are you happier? he asks, not looking at her.

No, she says. But I’m less sad.

He takes her hand. As he leads her to the pile, footprints bleed out behind their feet. The two sets of prints step together, intertwining as if in conversation, like two dancers together in a great hall far away. Together they comb through the potential parts of her, choosing the body she always imagined. A body built of stolen images, a collage of limbs, a kaleidoscopic stranger. He tries to help at first, choosing large full breasts, soft flowery thighs, picking for Katherine a body she doesn’t recognize, pouty rose lips, large almond eyes, but soon Katherine’s fervor outstrips him, and she pores through the piles of hair and flesh, losing herself in her own desire for self, rejecting his offers of hourglass hips or sleek black hair for the wavy brown locks of a beautiful girl who flirted with her boyfriend in their English class, the voluptuous arms of a woman she once saw on a bus, a mismatched quilt of bodies made beautiful by the paintbrush of memory.

Days pass as she rebuilds herself, perfection takes time. After that first night at home, she has been careful

to avoid her reflection. Ghostly ripples of skin in the water, her face in the hubcap distended and bent like a swollen kidney. She fears the new high cheekbones, the rounded nose, which she can’t stop feeling with her new, large hands. The parts of her body no longer know each other.

She hasn’t seen her parents in some time, returns home in her bus only in the dead of night to steal food. Every time she returns home she expects to see signs of panic, “Missing” posters, and crumpled tissues, or a missing placemat on the dinner table, or her boyfriend asleep on the couch, clutching his phone to his chest, waiting for a call that will never come. She imagines his familiar childish body, the round cheeks, and wide, smooth forehead. Before she even finishes dialing she regrets calling him, and each ring sounds forever in her new ears, high-pitched roiling clicks, has the phone always sounded like this?

Hello?

He sounds calm. She hears no worry in his voice, no sign that he has been crying or lonely. She listens to him breathe, small smooth streams of air, calm nose breathing, not the rough pitchy mouth sighs of despair. She hangs up the phone and closes her eyes and walks to the bathroom, relearning the way with her new hands and new legs. Tracing the lines of her house, each new sensation fills her with an alien recognition, as if her fingers are covered in wax. She opens her eyes.

To her surprise, she recognizes herself. The eyes in the mirror are not hers, nor are the cheeks, nor the hair, nor the chin, nor the skin. Yet, despite their individual foreignness, the little parts make up a face she recognizes indisputably as hers. She knows this face, she has seen it before. She always thought there would come a point where she had to choose between her new self and her old one, that her old life would fight for her, that her transformation would climax with a dramatic choice of identity. She had prepared for this. She had steeled herself against it. But the face doesn’t seem foreign. It seems friendly. She would talk to this person on the street. If there had been a climax, it happened without her.

She leaves for the bus, returns to the beach and the man and the pile of body parts washing up on the shore.

Nothing there has changed. He stands there, waiting and watching the ocean. He sees her and his mouth twitches in recognition. His lips are the same. He takes her in his arms, which she chose. The arms are the same. Are you happier? he asks.

No, she says, but I’m less sad. I’m less everything.

You’re more, he tells her.

She hugs his body with her new arms, holding his chest to her new breasts, large and beautiful and boring. The earth under her feet feels wet and crisp, tiny drops of water squeezed between tiny grains of sand. You’re almost done, he says. You’re so close.

He lets her out of his arms, the arms she chose so long ago, and walks to the pile of body parts strewn along the shore. He bends over and rifles through the pile and stands up, holding something dark in his hands. He holds it out to her, large and full, a red beating heart. This is it, she realizes. She looks at the heart as it pulses in his hand. She thinks about her old world, her home on the hill, no longer her home, her parents, no longer her parents, her boyfriend, no longer her boyfriend, her body, no longer a body at all, no longer a problem, no longer anything to her. And she thinks about her new world, her new body, her womanly body and this manly body across from her, and she takes the heart. The muscles jump in her hands, constricting in sections, beating just once.

Two seconds pass between the last beat of her first heart and the first beat of her new heart, dead. She can feel the blood course through her, new blood, new oxygen carried to new parts. She waits. He looks at her expectantly.

She feels expectant. What are they waiting for? What signal will they recognize? Nothing. She touches her hand to her neck and runs her fingers down her throat to the knotty bone in her collar down her chest to her breast, and stops, feeling the gentle subdermal pulse, like an unending tide. A heart is just a heart, a leg just a leg.

There must be something else, she says, and runs to the pile. There must be something else.

Katherine, he yells after her.

No, she says, don’t call me that, please don’t.

She changes everything she can. She replaces herself over and over, trying six pairs of arms, fifteen different pairs of feet, but none of them fit, none of them feel right or wrong, they just feel like feet. She turns around to show the man, but his lips tighten and the muscles in his cheek contract into hard knots.

You did this, she tells him. This is your fault.

No, he says.

You’re beautiful. What am I?

Beautiful, he tells her, but it no longer matters.

Then why did you make me change? she screams. Why did you make me?

As he stumbles back away from her, she is surprised at the force of her new adult arms. She is surprised by the clumsiness of his body, before so graceful, and she is surprised by the hurt she sees on his face. They look at each other and she sees the ocean behind him grow and swell, and she pushes him again deeper into the water, deeper into the waves, and he makes to move towards her, raises his arms, opens his mouth to speak, but anger burns in her new cheeks, and when a wave rises behind him she has the time for just one thought before it comes crashing down, a surprising, who is really betraying whom?, before the water crashes into his beautiful shoulders, knocking him down on his knees and into the sand.

No, not onto his knees, off of his knees. There, next to him, floating in the ocean, lay his legs, strong and muscular and disembodied. He looks at his legs, surprised to see them floating there next to him, until another wave hits, pulling his arms from his thick torso, thrashing him, dismantling him, unmaking him, ripping his surprised lips from his surprised face, stripping his eyes from his head, undoing everything that once made him a man. She is amazed how quickly it ends.

She looks at the once body in the water, the pieces of a man. She runs back to the pile and claws through it, looking for the old pieces of herself, but flesh blends into flesh, hair into skin, muscle into muscle, she sees an arm she recognizes, tries to crawl to it through a sea of limbs, wet and permeated by the ocean, loses the arm in the pile, sees a nose, or is it that nose over there? or this one? and under that torso, a hand she recognizes, and she dives through the flesh and sand, and grabs for the hand and she hears a screech behind her and dives to avoid a great white bird, a seagull that swoops and flies away with a familiar hand in its beak. She searches longer, finds nothing, and finally she stops. Looking up the beach at the bus parked in the sand and the forest and the gravel path to her house, she imagines she can see her home, though she knows she cannot, and she imagines the yellow lights in the window and small blurry shadows of people moving about the rooms, setting the table for dinner, lying in bed, and walking down the stairs for dinner every day, going to work, reading. She walks back to the ocean. She remembers the first foot on the beach, the great potential of a single foot.

She climbs into the water and stands amidst the destroyed body of the man she built. The surf pounds, throwing his limbs, grinding his flesh, now beginning to melt away. Ground into dust, broken into pieces, pulled into the sand beneath her. She floats there hoping the waves will find her, will pull her apart too, break her into pieces, but she floats there, unhappily whole, still she floats there, still she floats.

Fiction • Winter 2013 - Origin

Even at forty years old, Leo indulged his younger brother. He stood at the kitchen counter and loaded a Hi8 tape into the Handycam that he and Charlie had found when they were packing up the basement. Leo pressed the cassette compartment back into the camera, and the metal frame set the black tape into place. Charlie clutched a candlestick and stared into the lens with the expectant attention of a newscaster. “Do you have to do that?” asked Leo.

Charlie grinned. “Is it on?”

Leo scrutinized the miniature of the room cast in realtime on the small, flipped-out screen. It looked unfamiliar, like it belonged in the pages of a catalogue. He pressed the red button with his thumb, and REC appeared in red digital letters. “Alright, you can start whenever.”

“Hello! For the purposes of posterity, I am Charlie, Leo is filming, and this is the kitchen. Mom will not be happy that it’s a mess, but that’s probably more accurate in any case.”

The kitchen was in disarray, although it was not familiar daily clutter. Nearly everything had been pulled from the cabinets. Cans were stacked on the counter to the left of the stove and perishable items were placed on the right. On the table were plastic bins, which held pots and pans with newspaper stuffed into the gaps. A box labelled “Very Fragile” in permanent marker held stacks of plates. The refrigerator was bare except for a bottle of milk, a mostly empty carton of eggs, and a container of lo mein from the night before.

“The style is French Country—very rustique. Note the hanging pots and pans.” Charlie gestured towards the ceiling. Although his hairline had receded slightly, his face was still boyish, and on the small screen he could pass for as young as twenty-five. “What else to say. The oven runs hot. Take five or ten minutes off of all cooking times. Maybe give a quick three-sixty, Leo.”

Leo panned obligingly around the room, sweeping along the cabinets, stove and sink. The appliances had all been packed up.

“I’ll be glad someone will be cooking for mom now. Little old lady with a gas stove was starting to make me nervous. And next up we’ll make our way into the dining room.”

Leo backed out of the kitchen and turned to the swinging door, the camera coming right up to the slatted wood until the peach room burst suddenly into the frame. The dining room was a formal space, used more around holidays than any other time of the year. For the most part it lay dormant, though it took up nearly a quarter of the downstairs. It was almost completely empty, with the lacquered table and chairs sitting in the center of the room on the decarpeted floor, and the wall where the sideboard had been slightly darker.

“This is probably the least exciting room of the house. The most exciting part of it is the door to the basement, and only because the basement is a horrible place.” Leo zoomed into the stairway door as Charlie spoke. “Why don’t you give this one a three-sixty, too?”

“I did when we came in.”

As they passed the bathroom, Leo flashed the camera inside, quickly focusing on the sink knobs, which had the hot and cold reversed.

The living room was a mottle of things. The corner by the dusty-brown upright piano was crowded with cardboard boxes in various states of closure, with two packing tape dispensers and shreds of pink and clear bubble wrap littered on top. The big floral sofa was noticeably absent, replaced by a cream showpiece that the real estate agent had selected so potential buyers could better impose their own imagined rooms onto the space. The low shelves had been cleared of the frayed gardening paperbacks and their father’s old French textbooks to make way for a Complete Works of Shakespeare and a jar of polished stones.